Have you ever had someone depend entirely on you? Or have you ever depended entirely on someone else? Kinship, an exhibition at Kunsthall Trondheim, joyfully captures these deep connections through the story of an artist and a dog. Featuring drawings, sculptures, and a newly commissioned installation of one hundred ceramic objects spanning two gallery floors, Kinship invites reflections on your own interdependence with others while embracing your animal self.

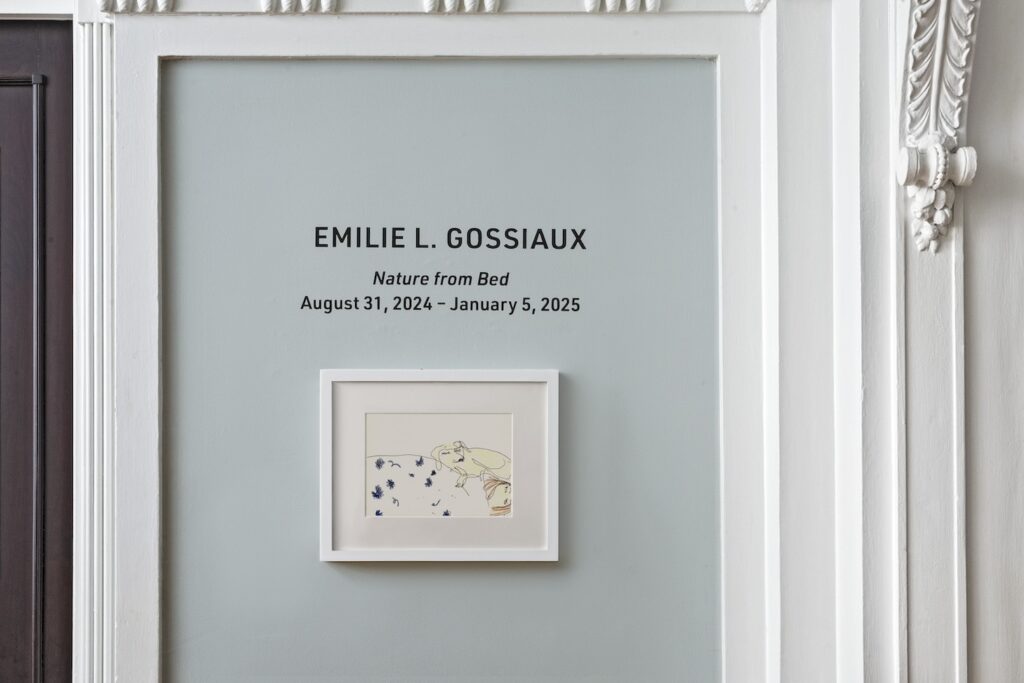

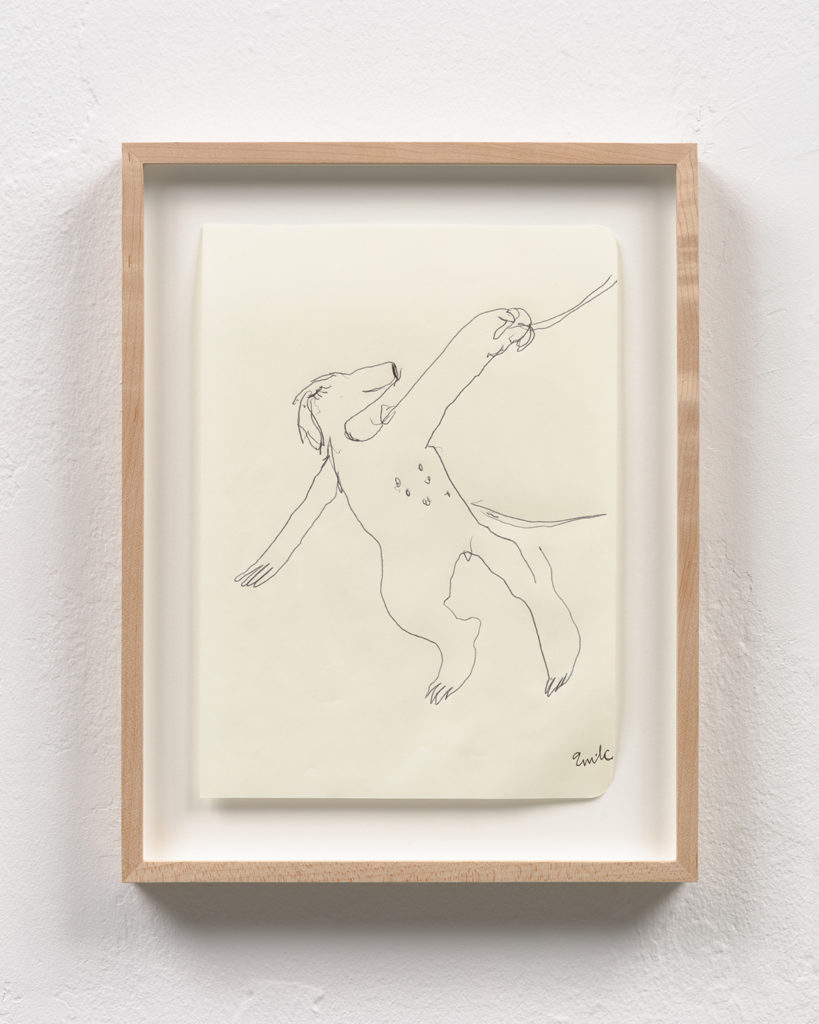

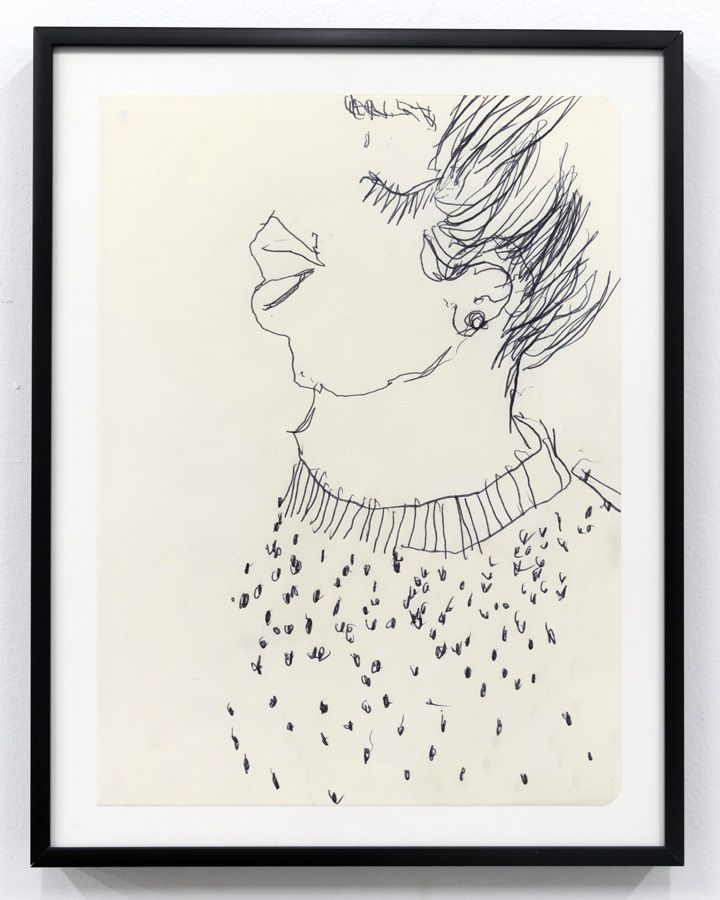

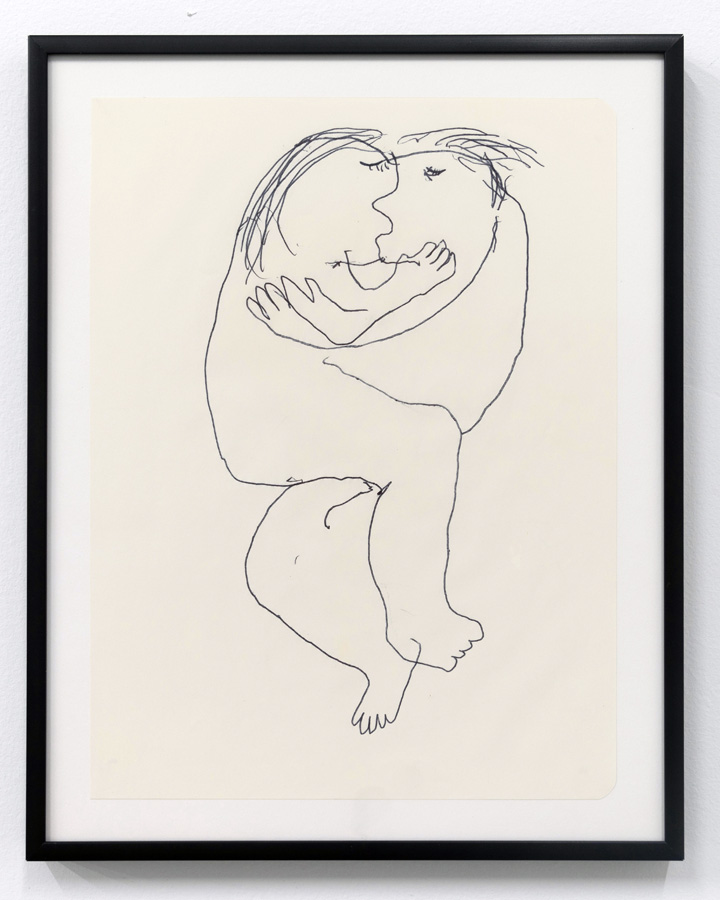

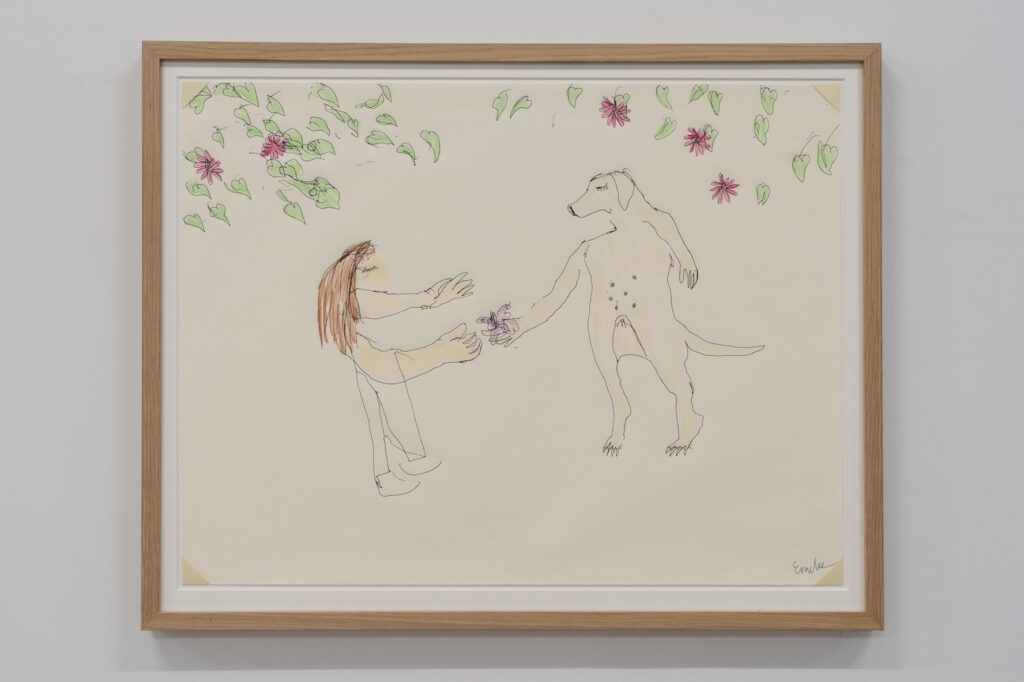

Artist Emilie Louise Gossiaux first met London, a blonde English Labrador Retriever, the day after her 24th birthday. Born three years earlier, London entered Emilie’s life just two months after a traffic accident caused Emilie’s blindness. Since then, for over a decade, London has been not only Emilie’s guide dog, but also a close companion and muse.

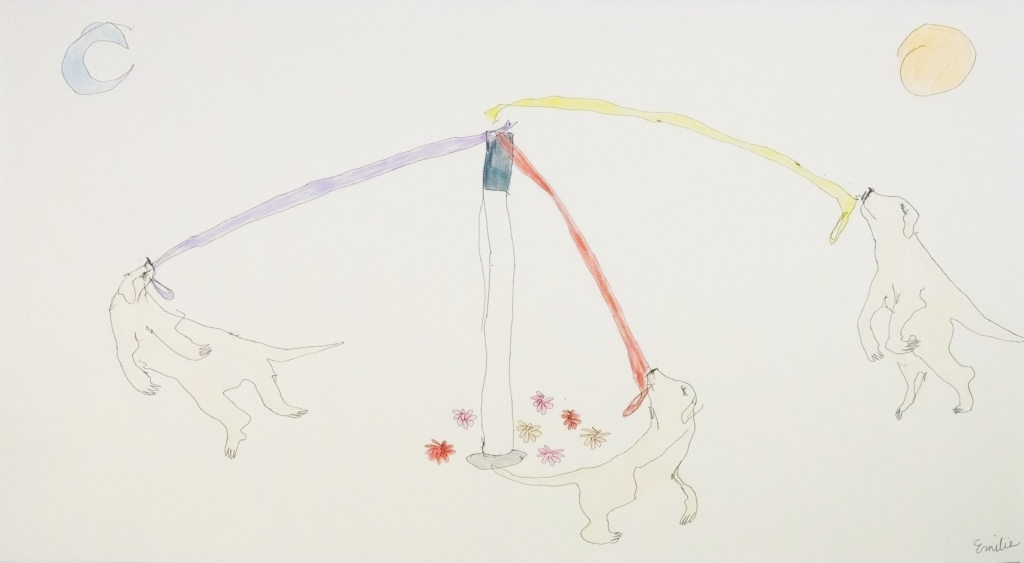

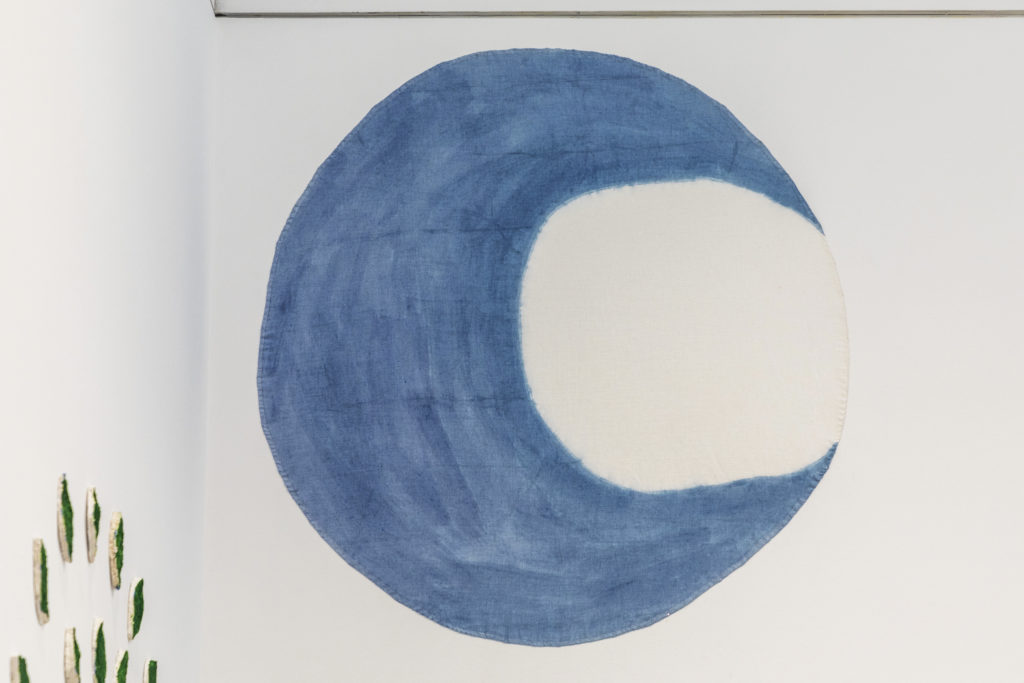

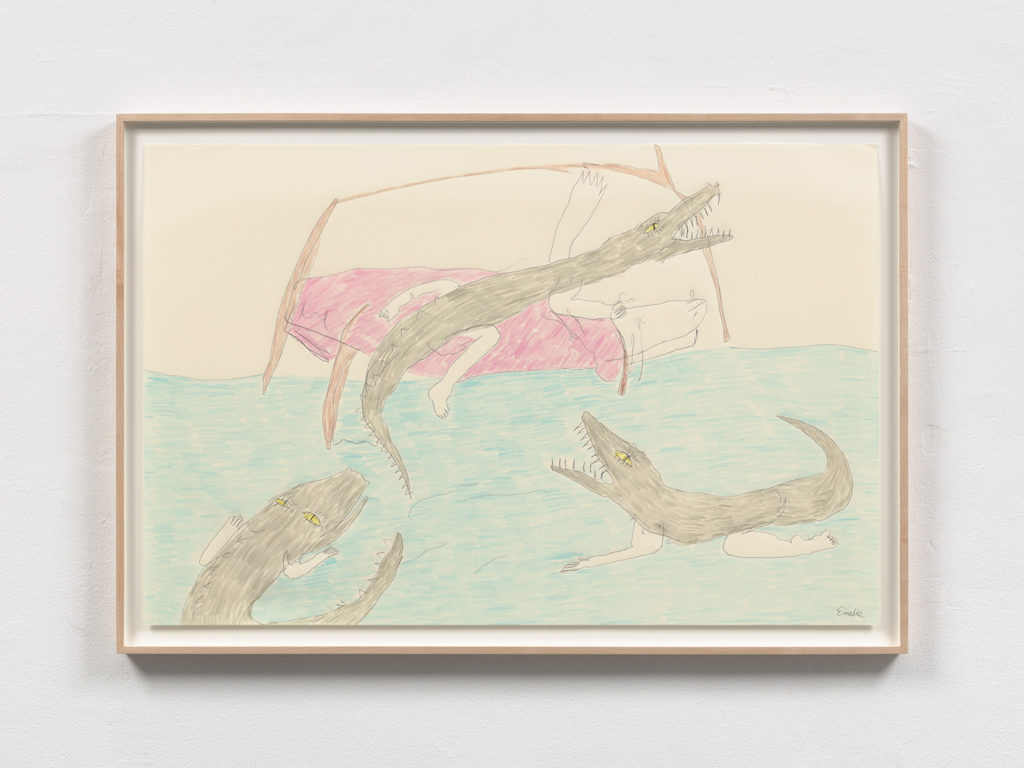

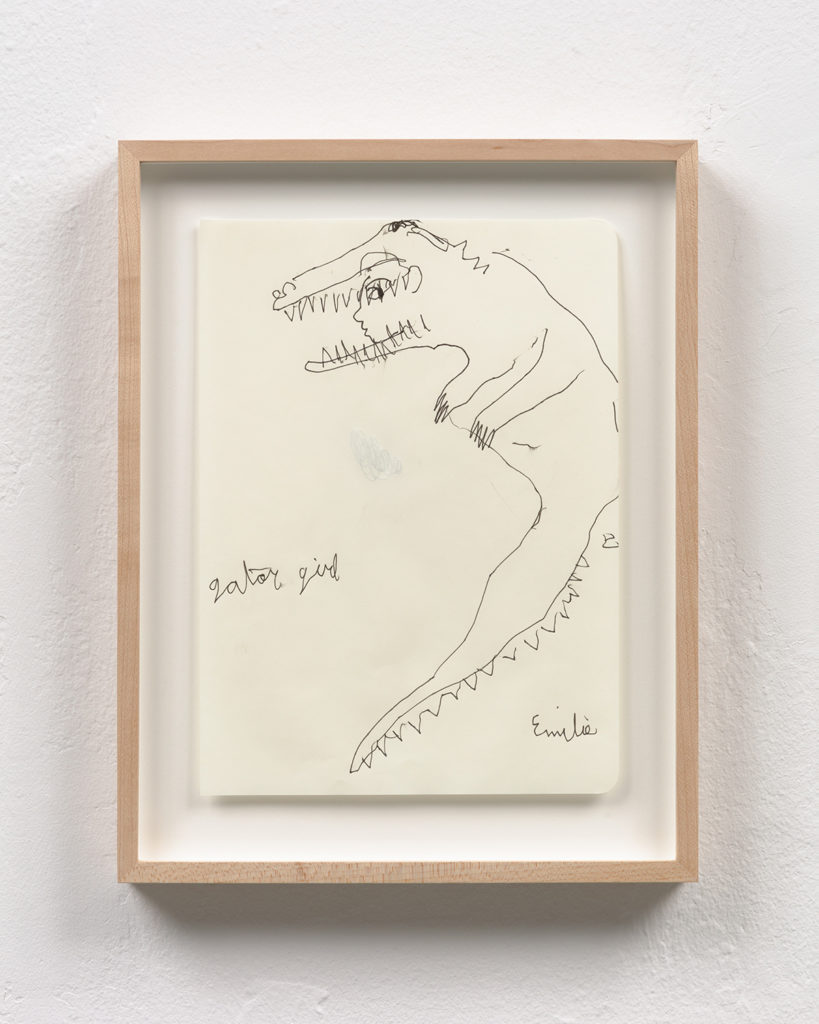

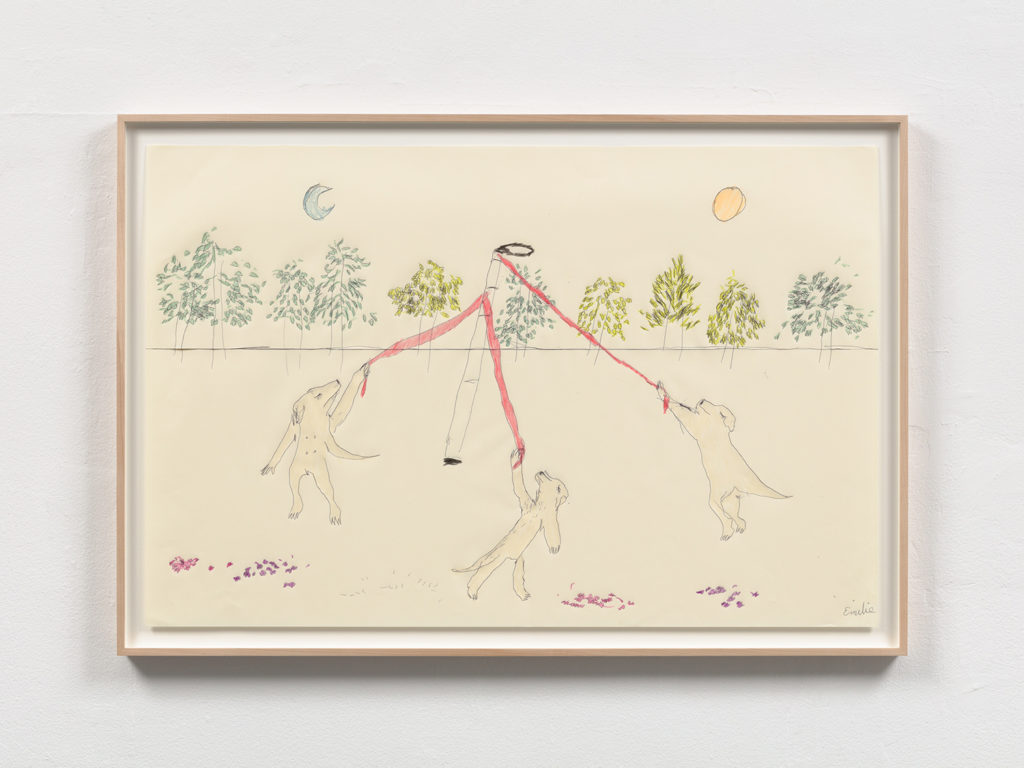

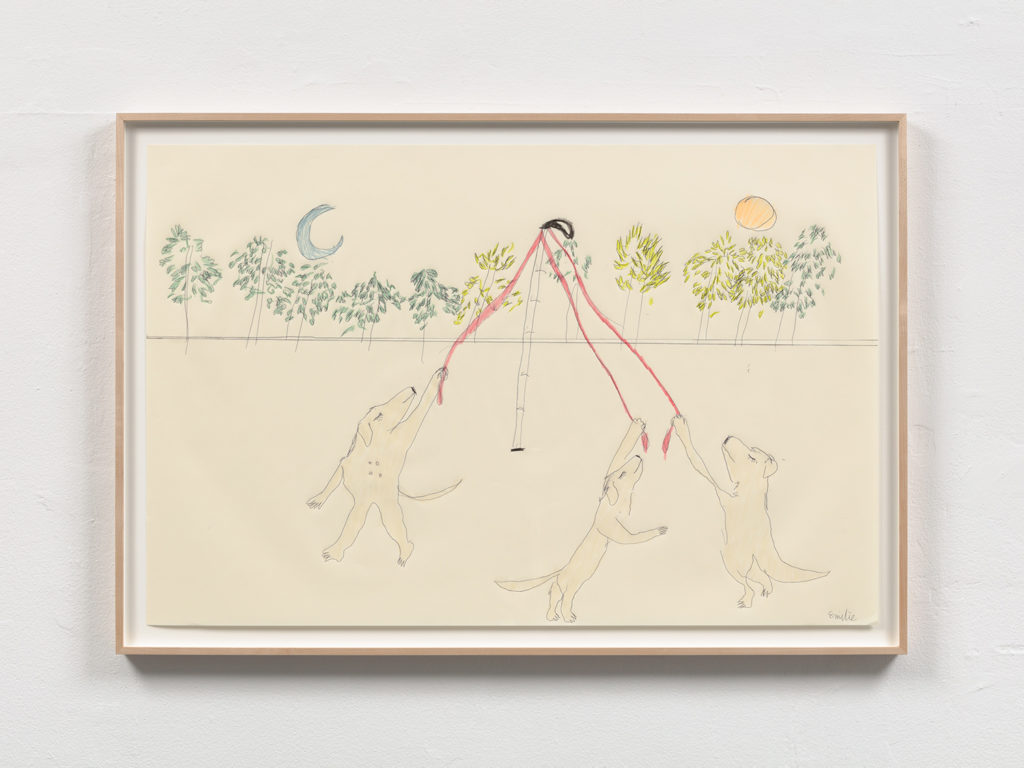

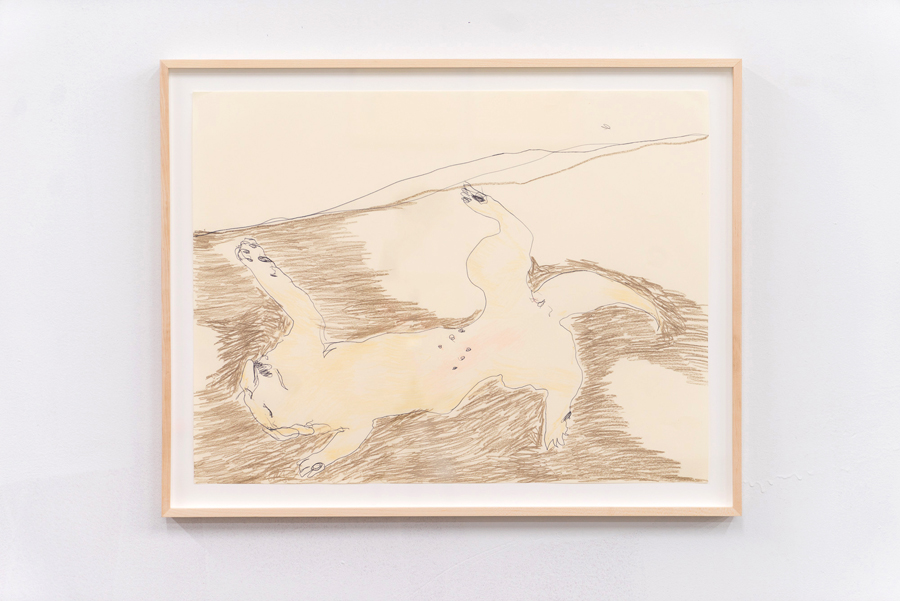

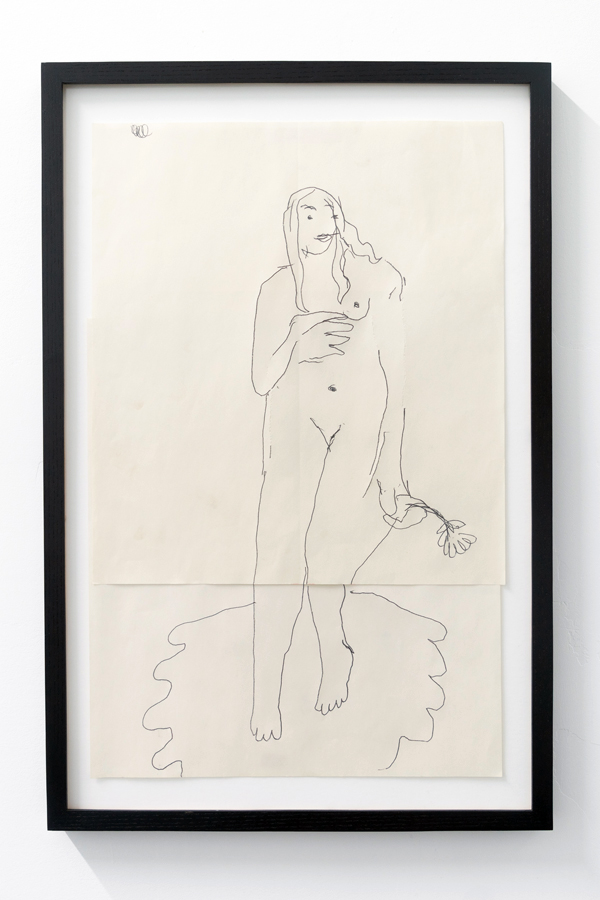

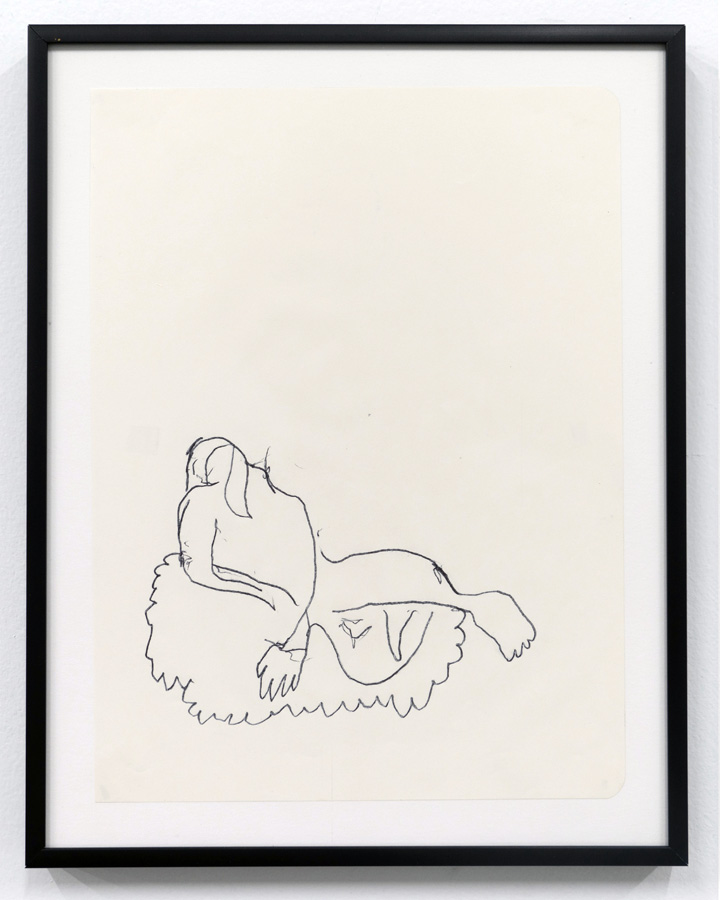

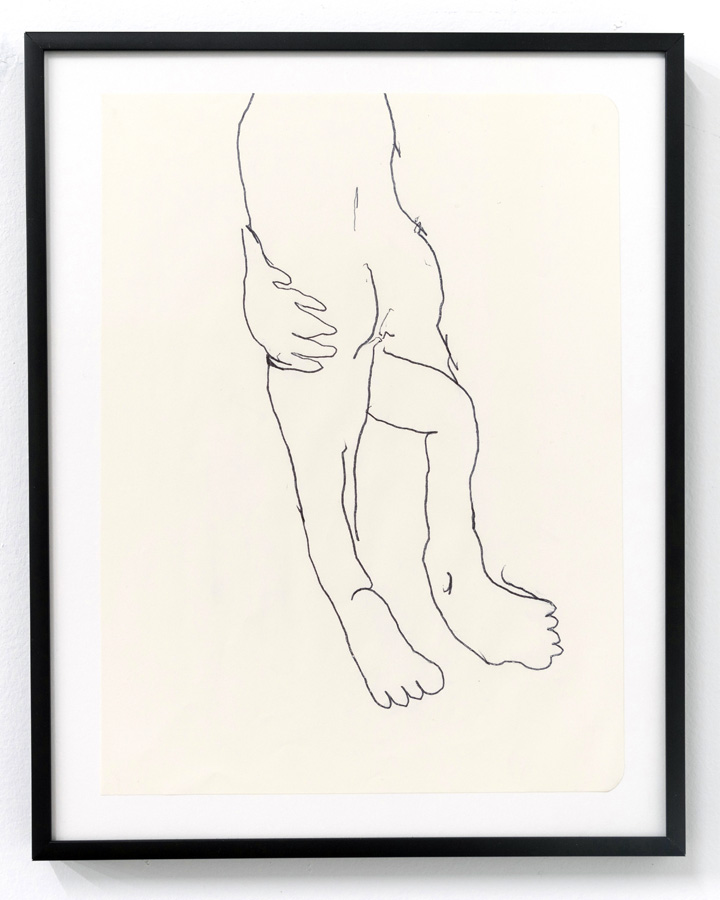

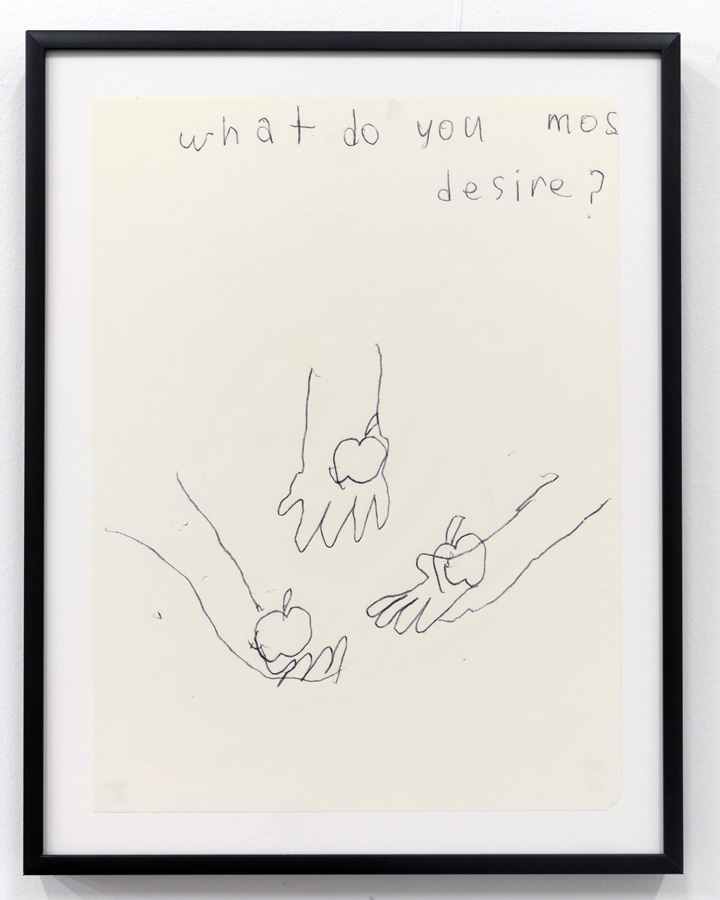

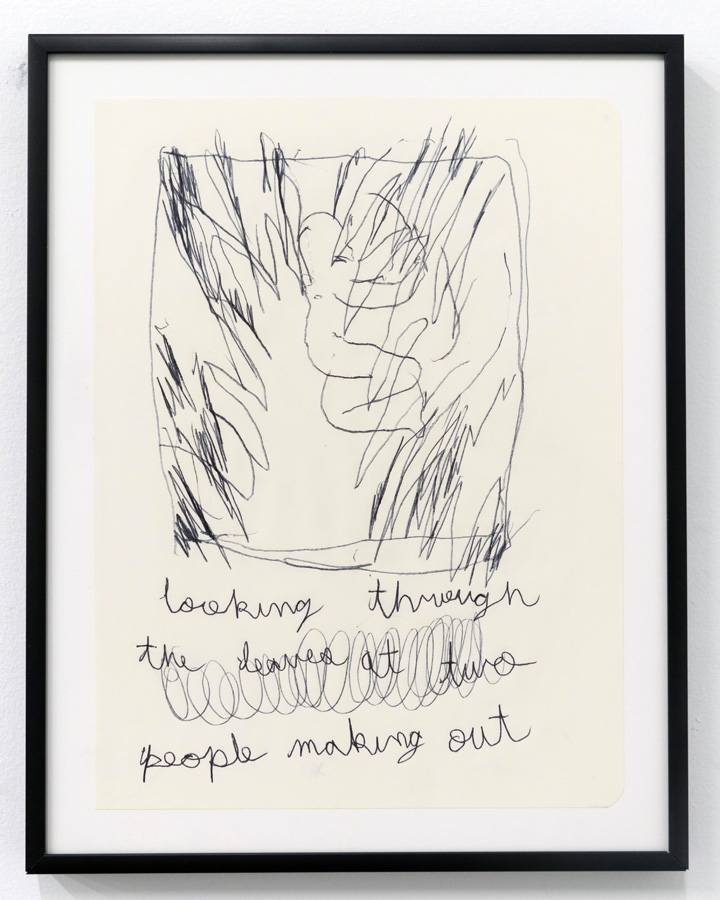

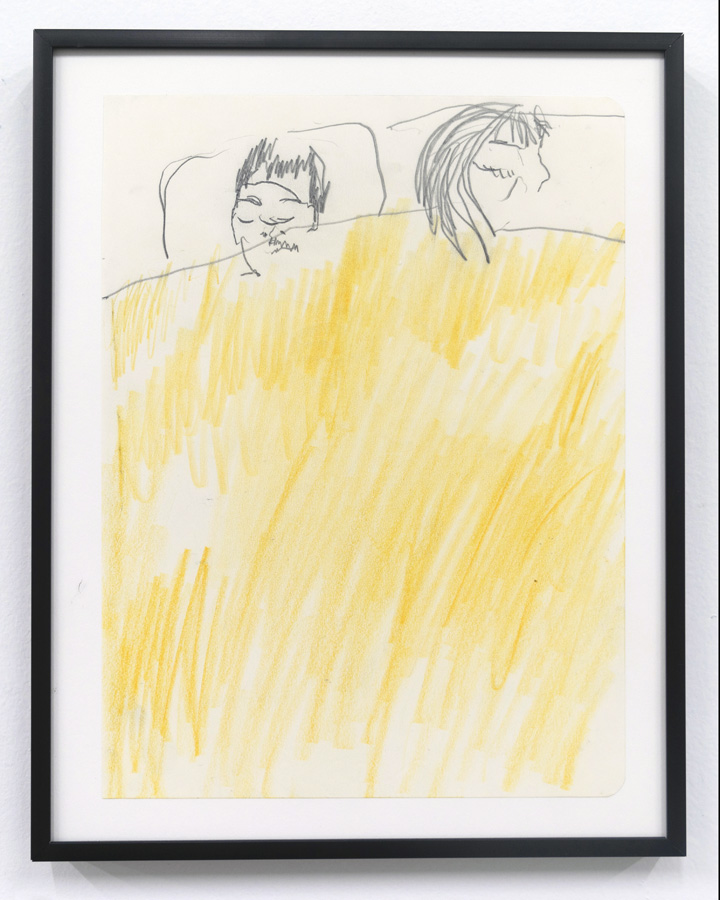

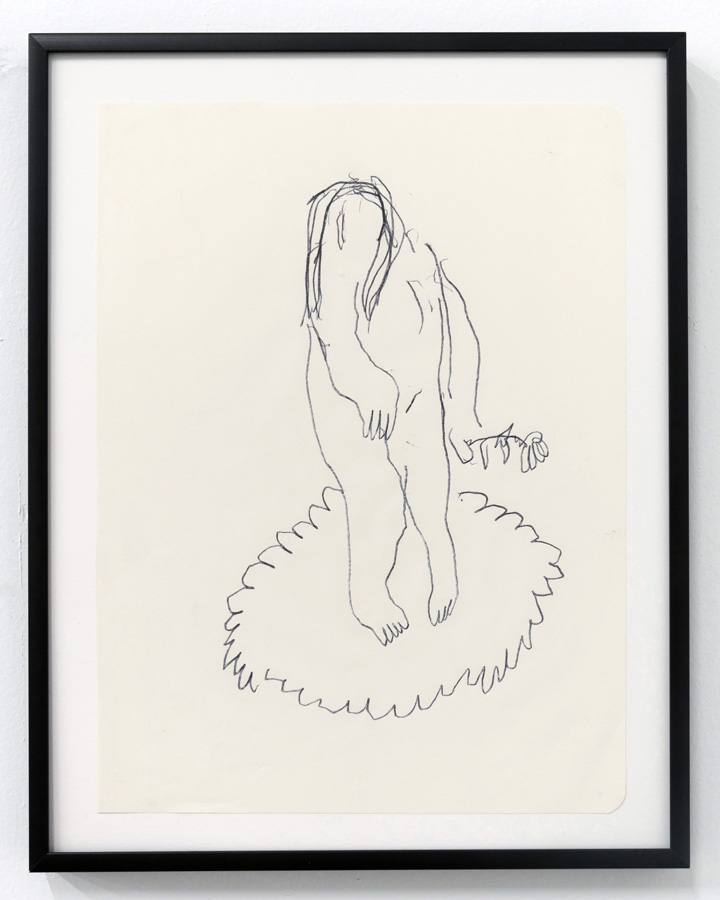

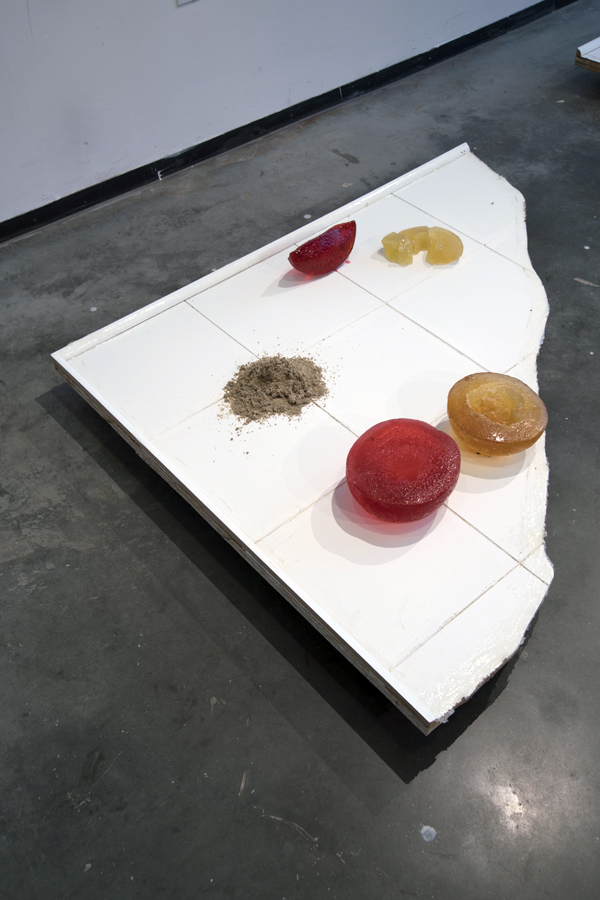

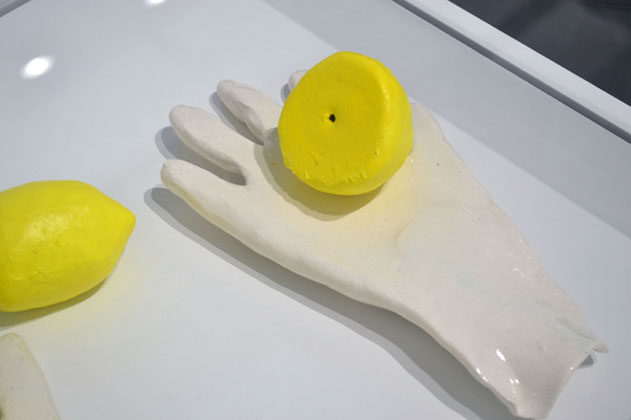

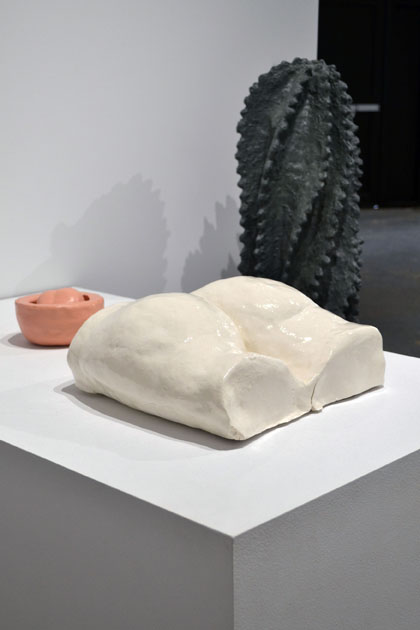

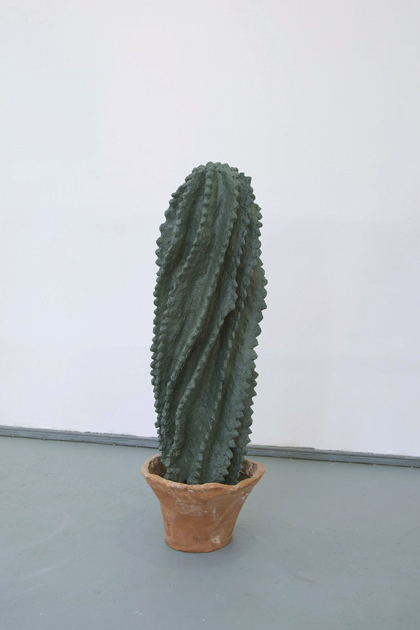

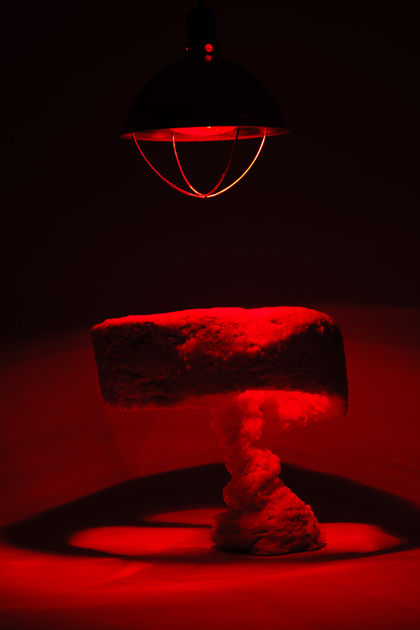

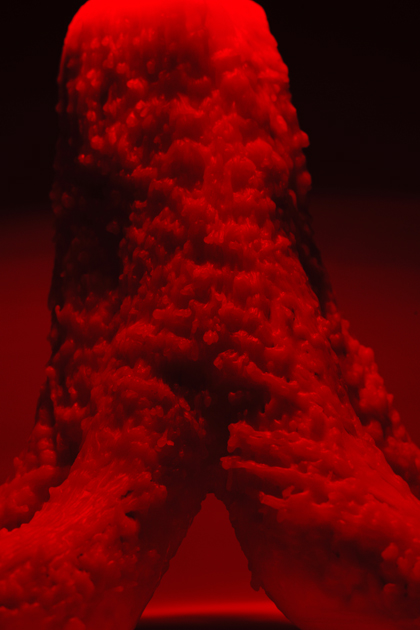

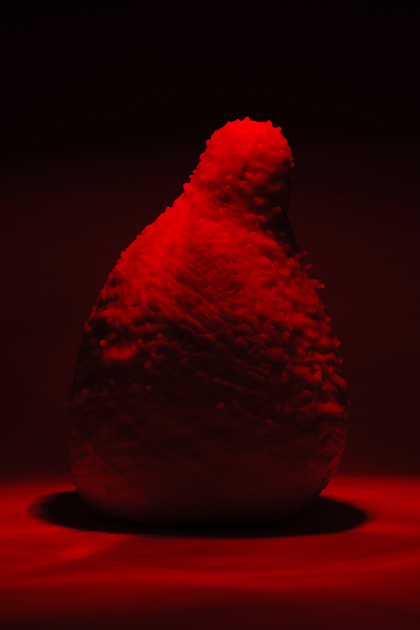

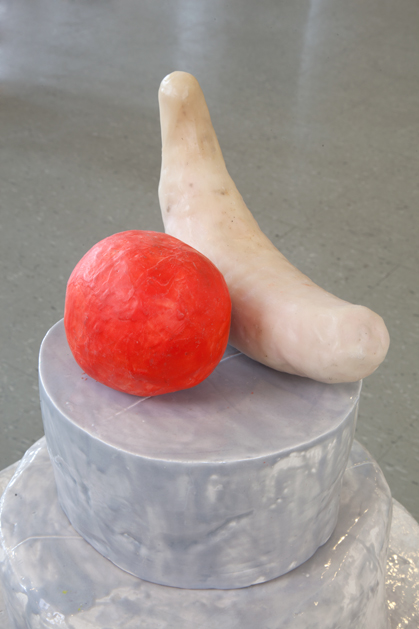

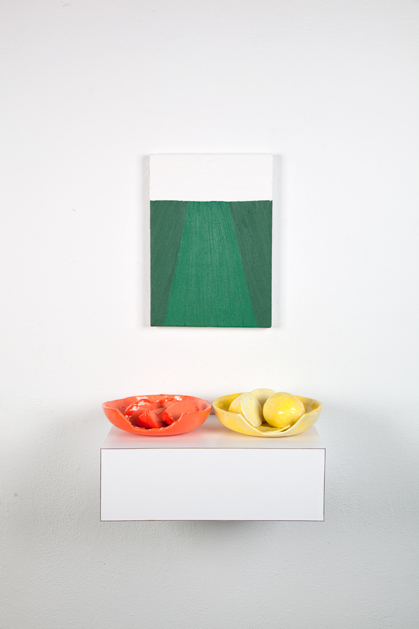

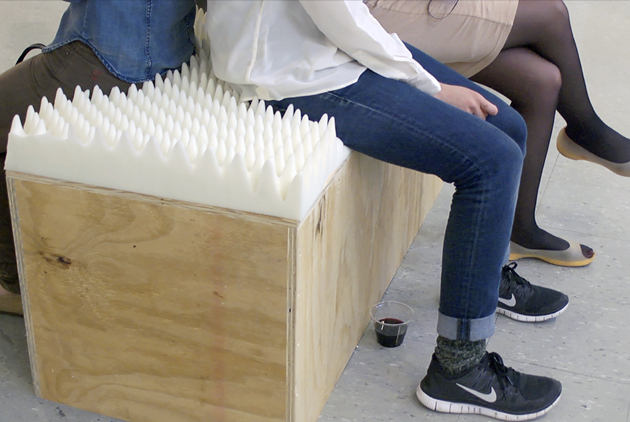

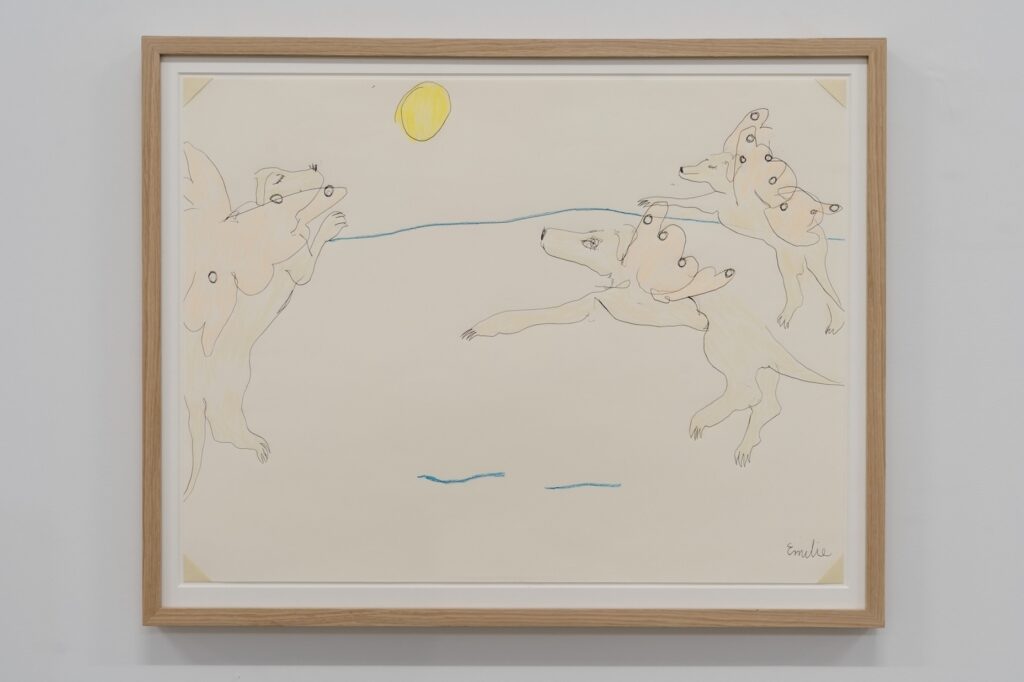

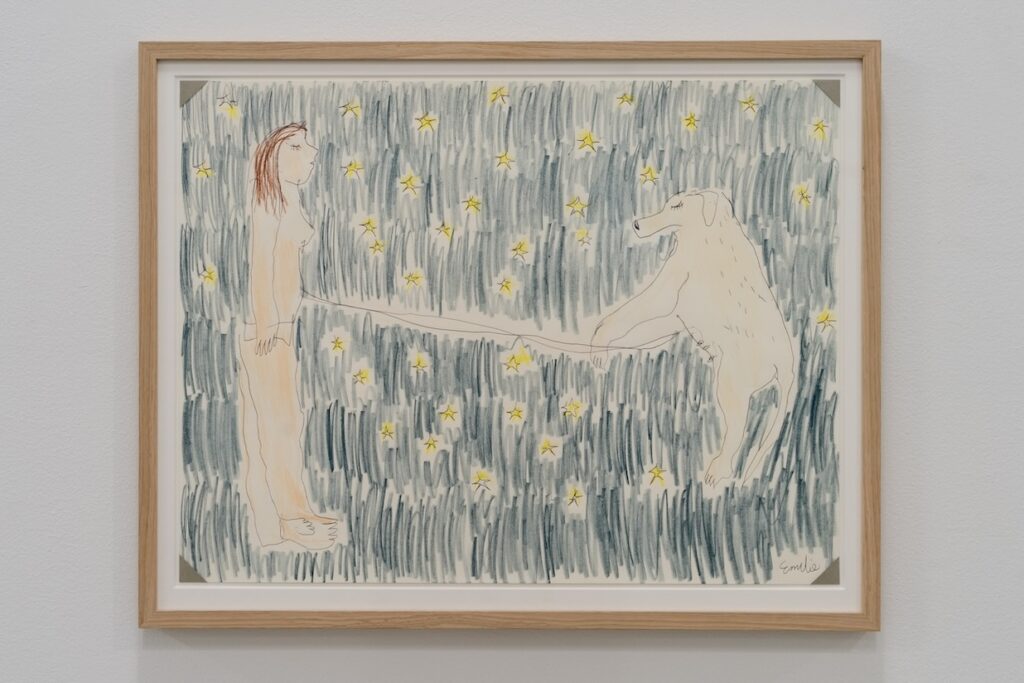

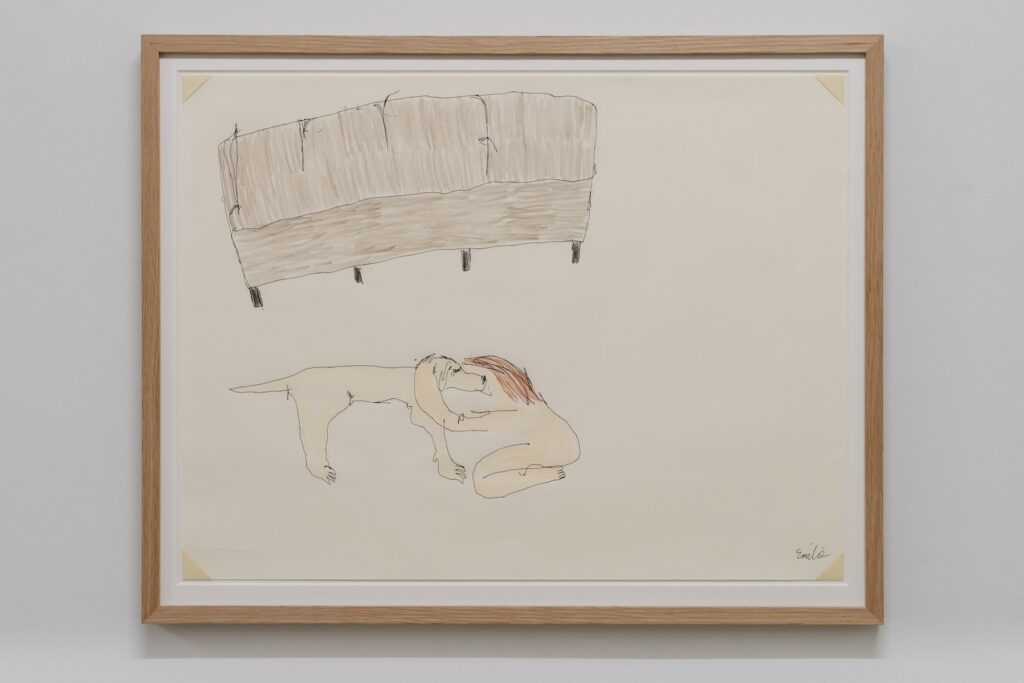

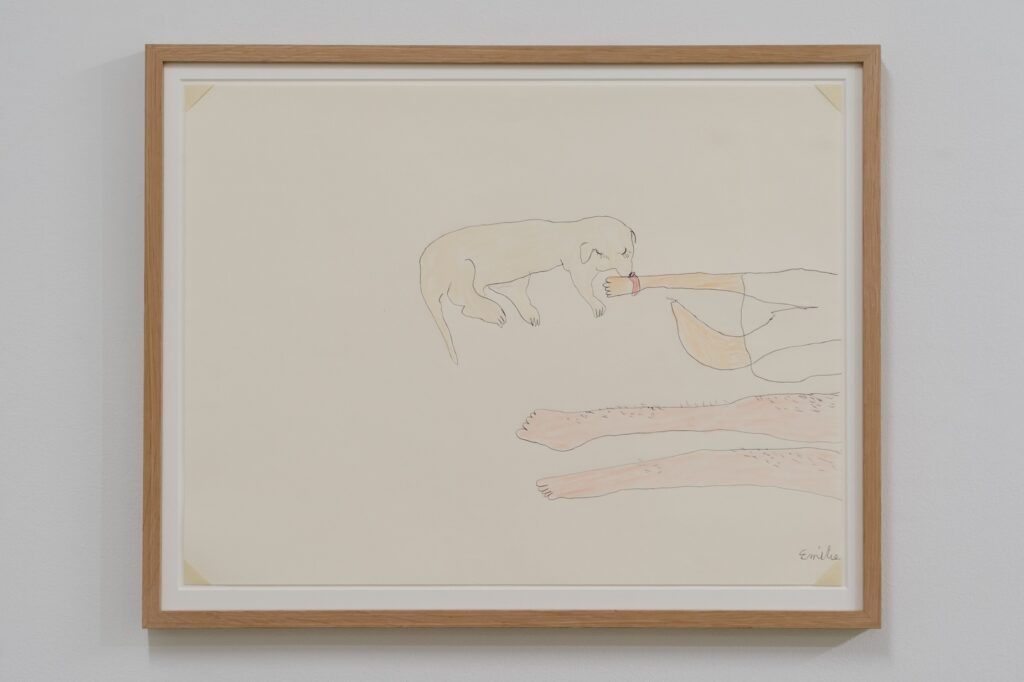

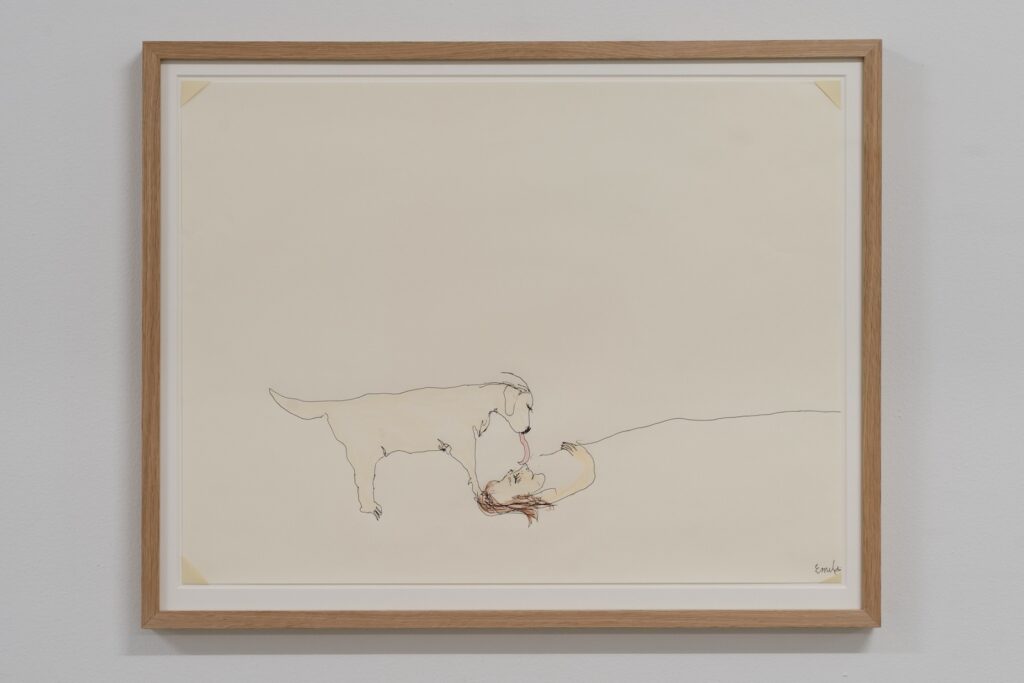

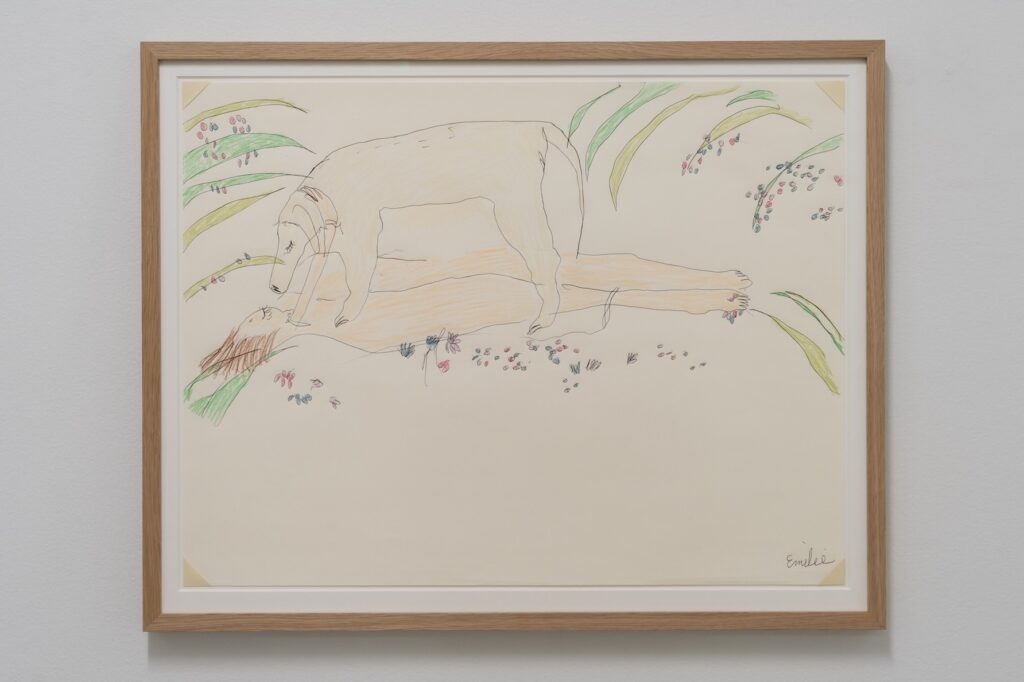

In Kinship, visitors follow a trail of multicolored ceramic sculptures of various sizes, inspired by the design of “Kong” chew toys—snowman-like rubber structures made of stacked spheres and often used to hold doggie treats. Along this trail, a survey of the artist’s work is presented through a series of vignette-like displays. From one to the next, sculptures and drawings chart the interplay of Emilie and London’s lives and bodily forms to celebrate their shared experiences. Together, they form a unified whole—a super-being that transcends hierarchical boundaries.

Beyond honoring these bonds, Kinship challenges the distinctions between non-disabled and disabled individuals, as well as between humans and animals, by highlighting our mutual interdependence and co-evolution. These themes respond to Emilie’s personal experiences of dehumanization and discrimination while traveling with London. Instead, Kinship opens new perspectives that foster greater empathy and respect for both animals and “Crip” individuals. It encourages a rethinking of how we engage with other species and highlights the need for inclusivity and recognition of diverse forms of life.

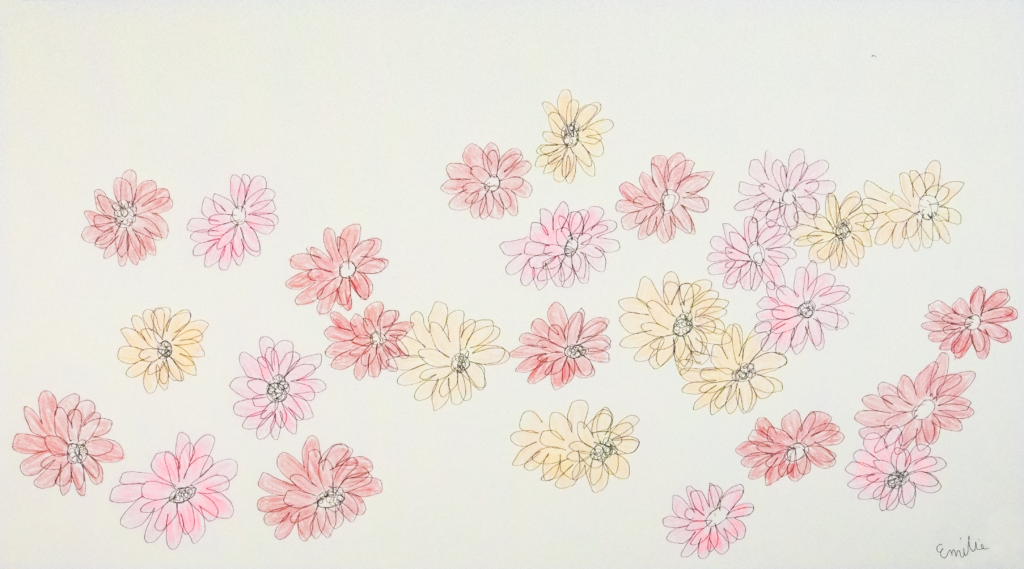

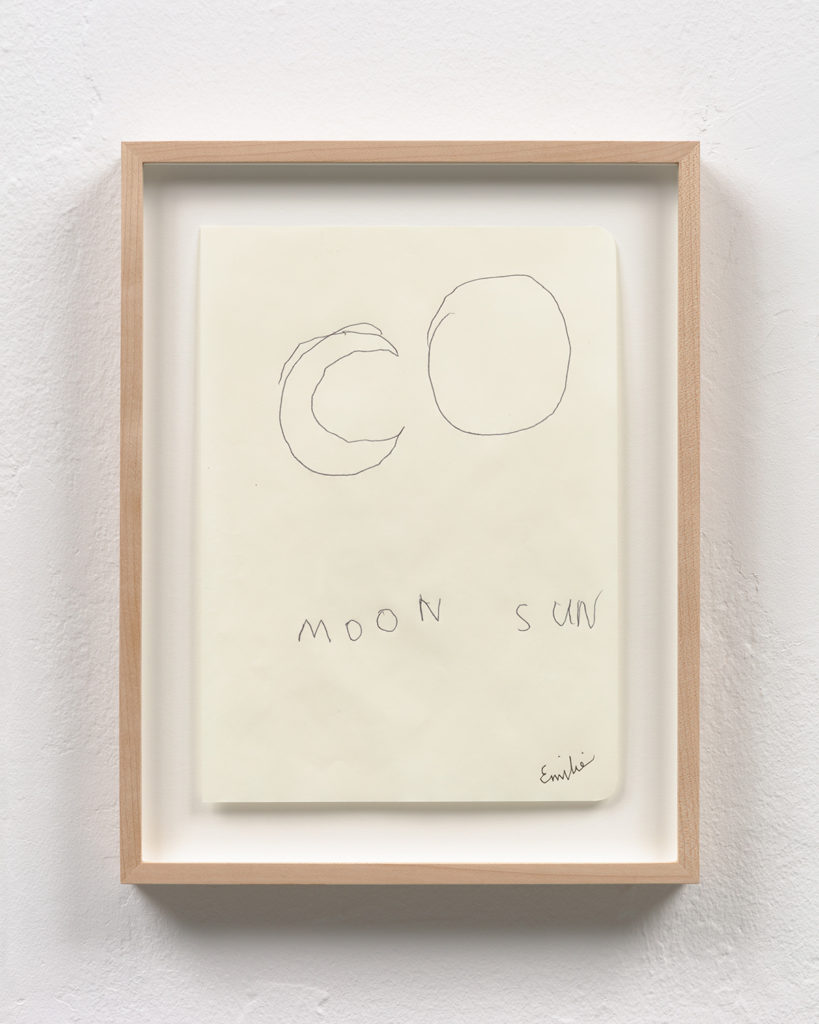

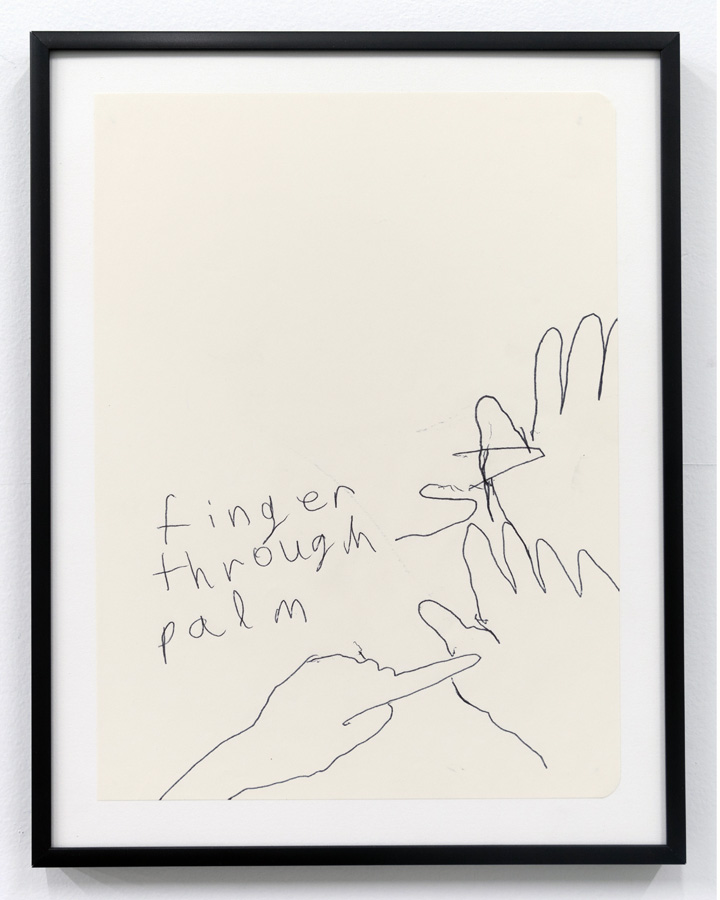

To meet these calls, Emilie infuses her work with a profound sense of disability pride and the morality of animal rights. She addresses the intersection of disability activism with animal welfare, emphasizing that the treatment of nonhuman beings often reflects broader societal attitudes toward disability. The sensory quality of the artist’s pieces, crafted through memory and touch, encourages viewers to experience art in an unconventional way, reflecting the tactile connection the artist has with London. Every drawing and sculpted form becomes a celebration of their shared journey, making Emilie’s art a testament to the beauty of connection and to the unspoken, species-transcendent language of love and trust.

In a first for Kunsthall Trondheim, the gallery will offer both audio descriptions, and a braille guide for this exhibition, which is the artists first European solo-show.