Dogs Who Run In Dreams

May 8 – June 14, 2025

Opening Reception: Thursday, May 8 | 6-8pm

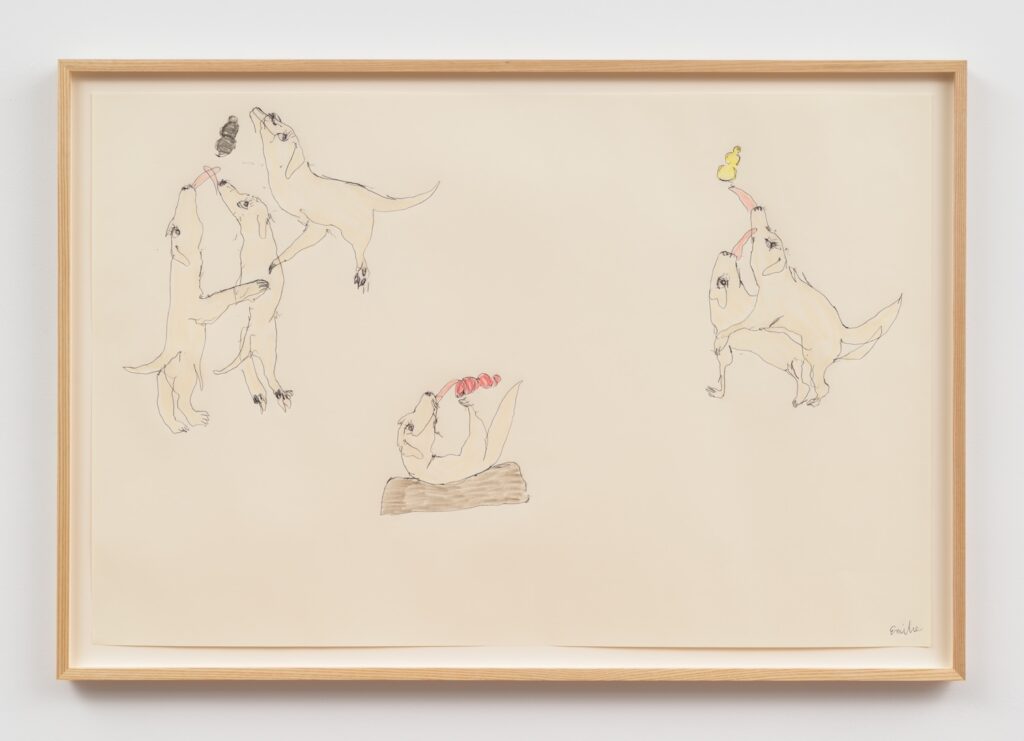

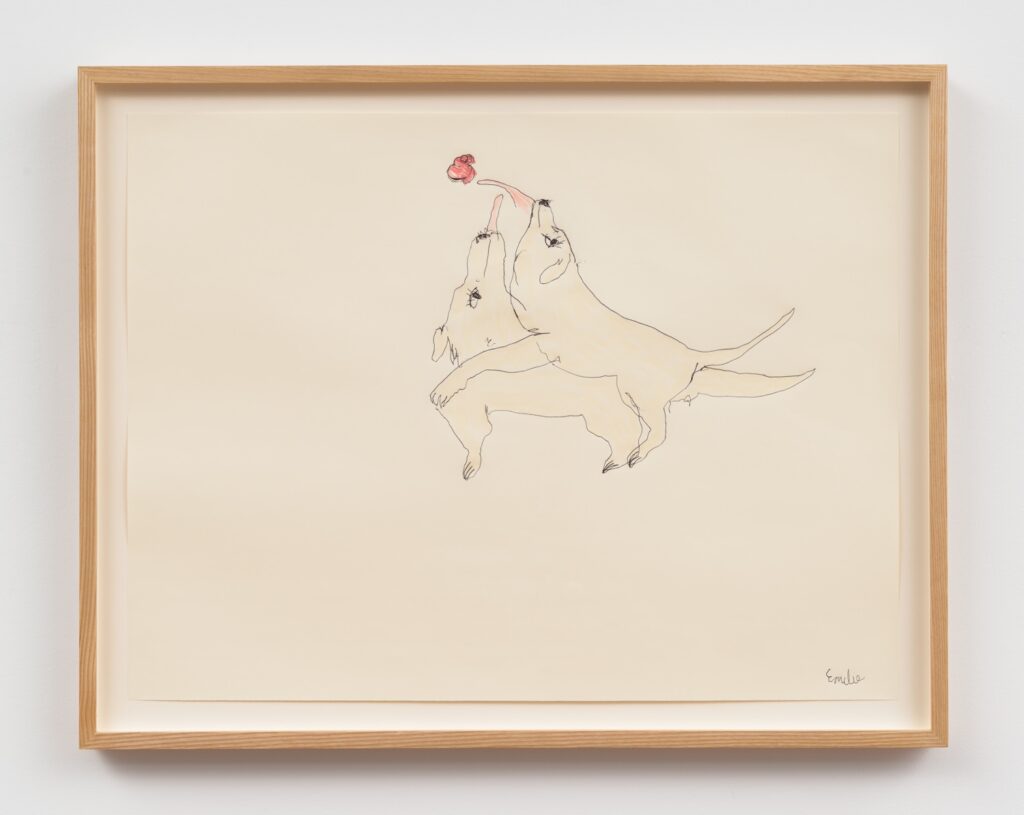

David Peter Francis is pleased to present Dogs Who Run In Dreams, a solo exhibition of work by New York- based artist Emilie Louise Gossiaux. As a multidisciplinary artist who is also blind, Gossiaux translates her inner worlds into the physical realm through works based on dreams, memories, and her sense of touch— an exploration of interdependence, Disability, and the interspecies kinship that centers the decade long relationship with her Guide Dog and animal companion, London.

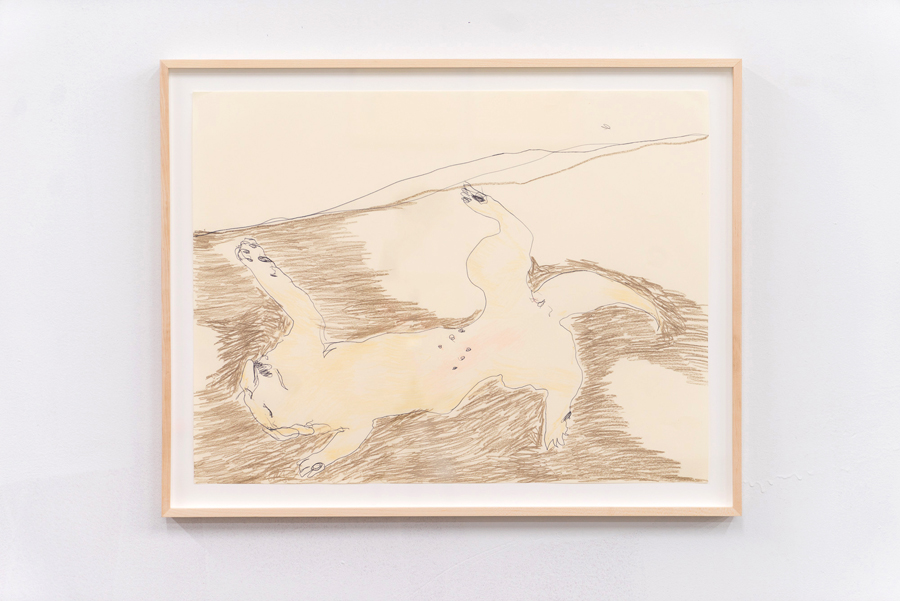

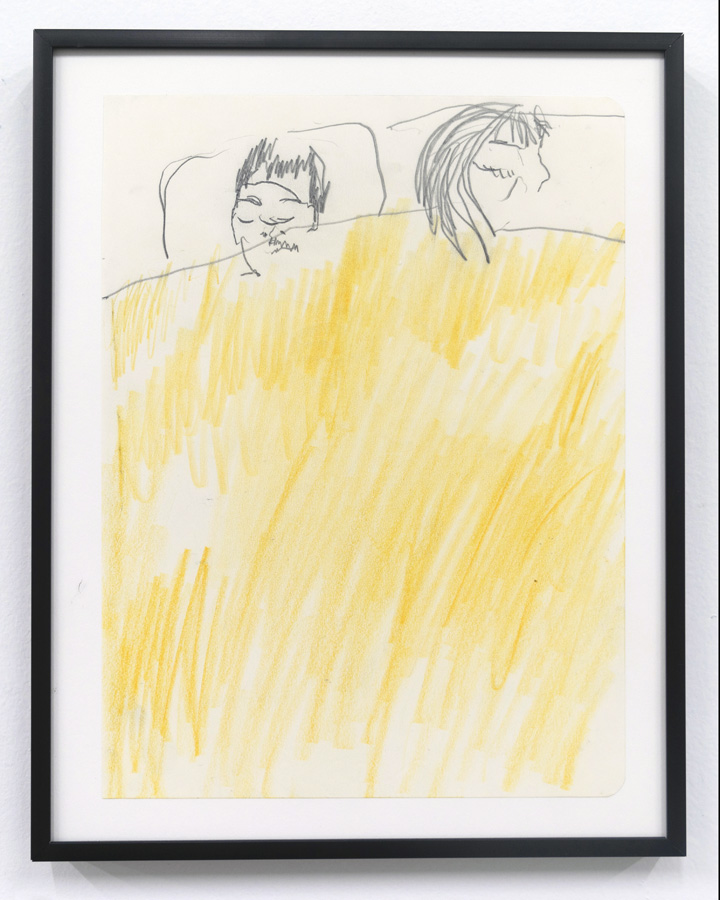

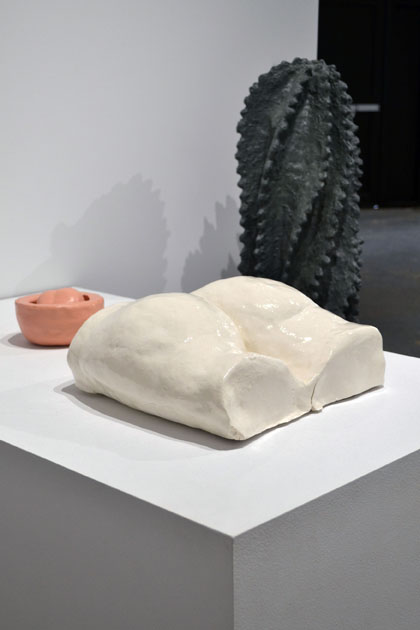

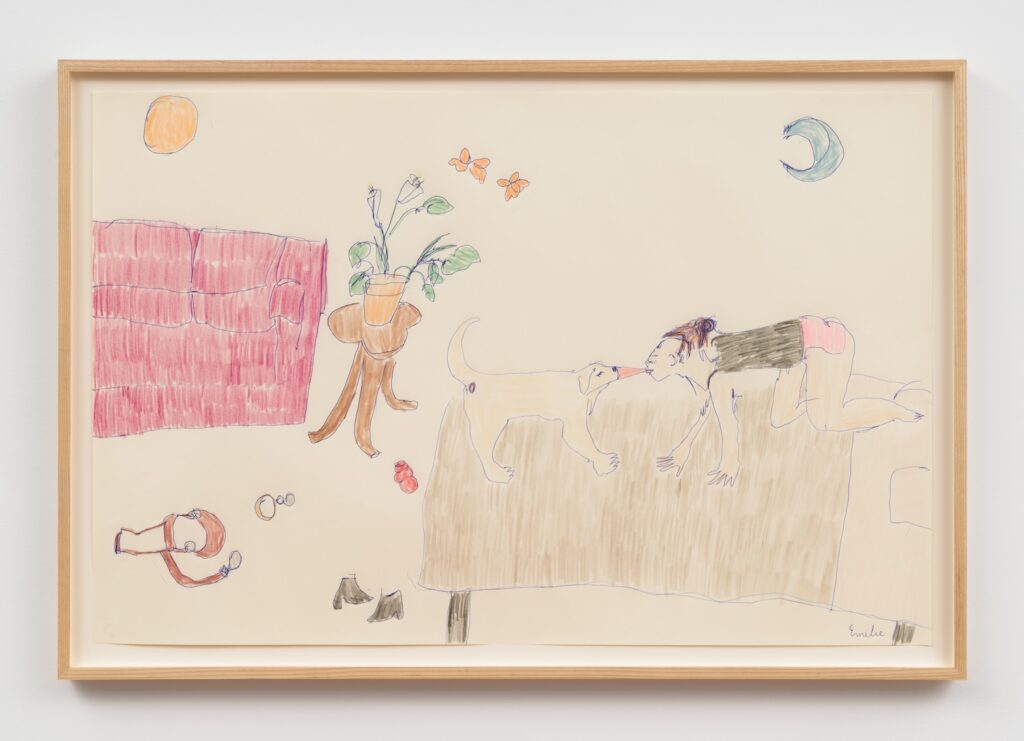

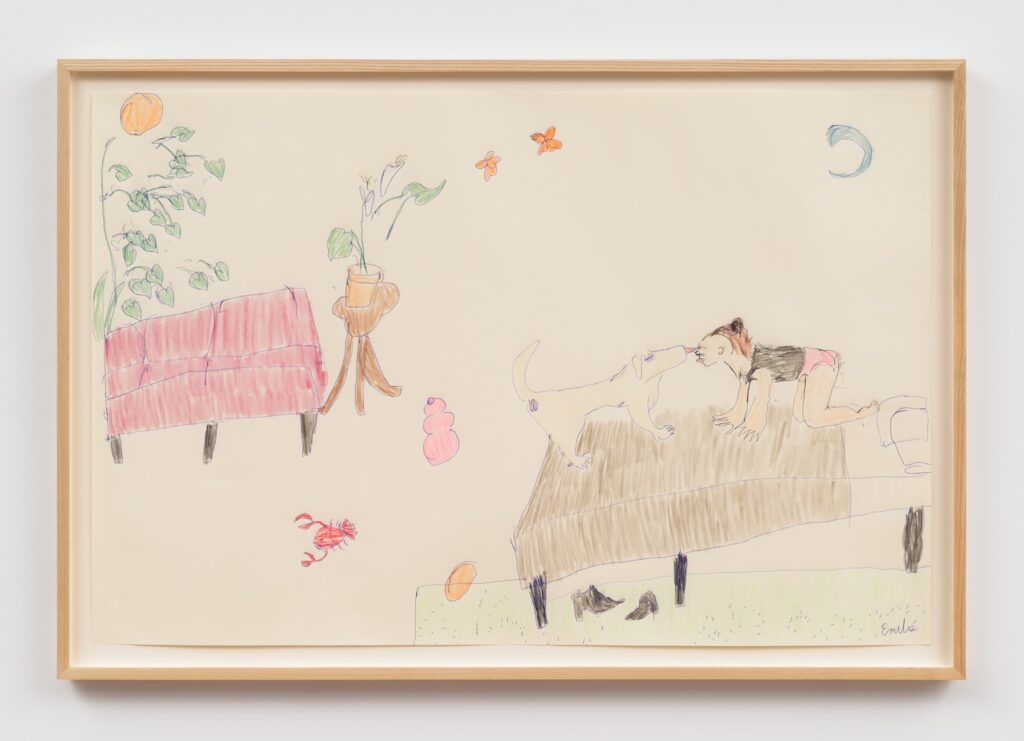

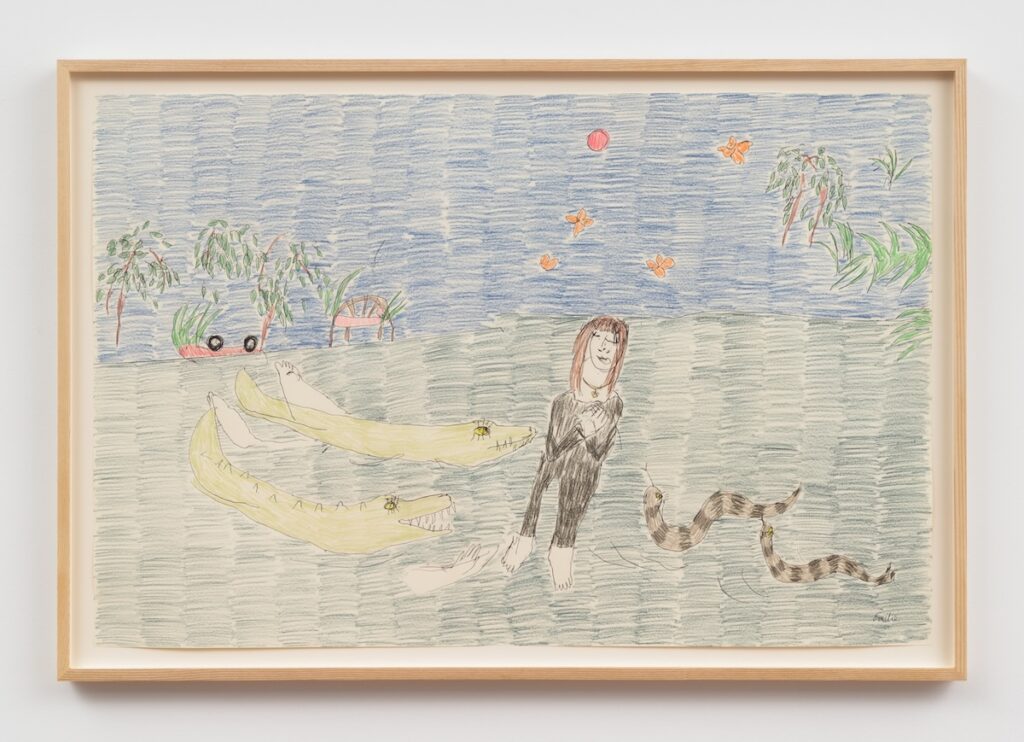

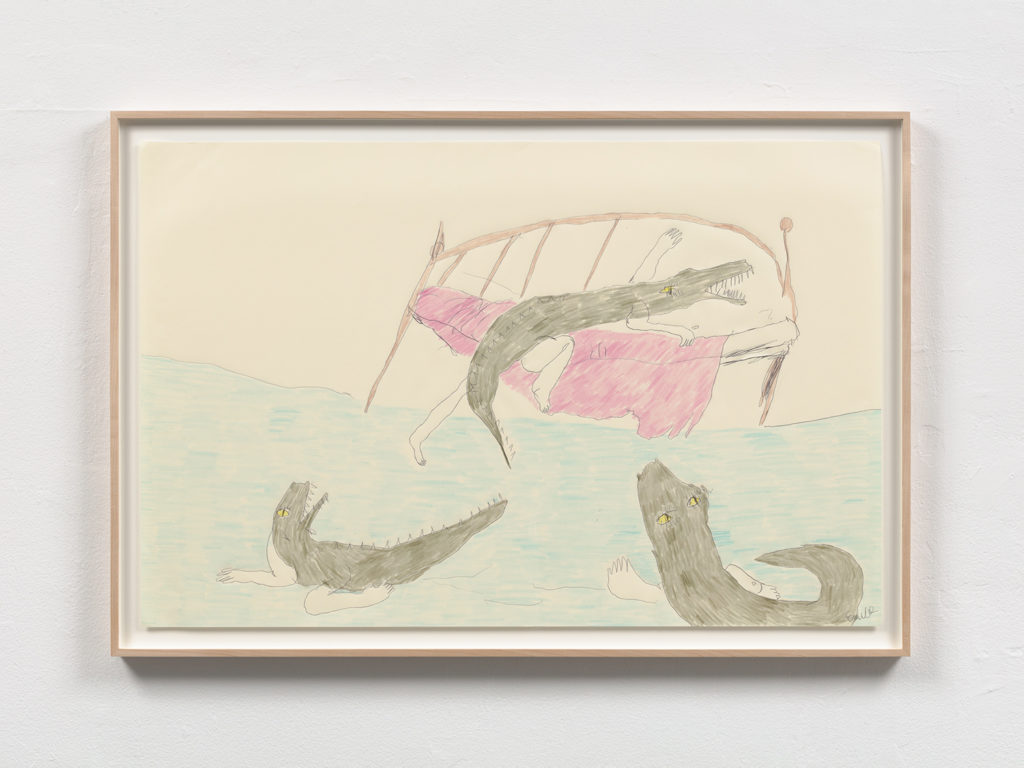

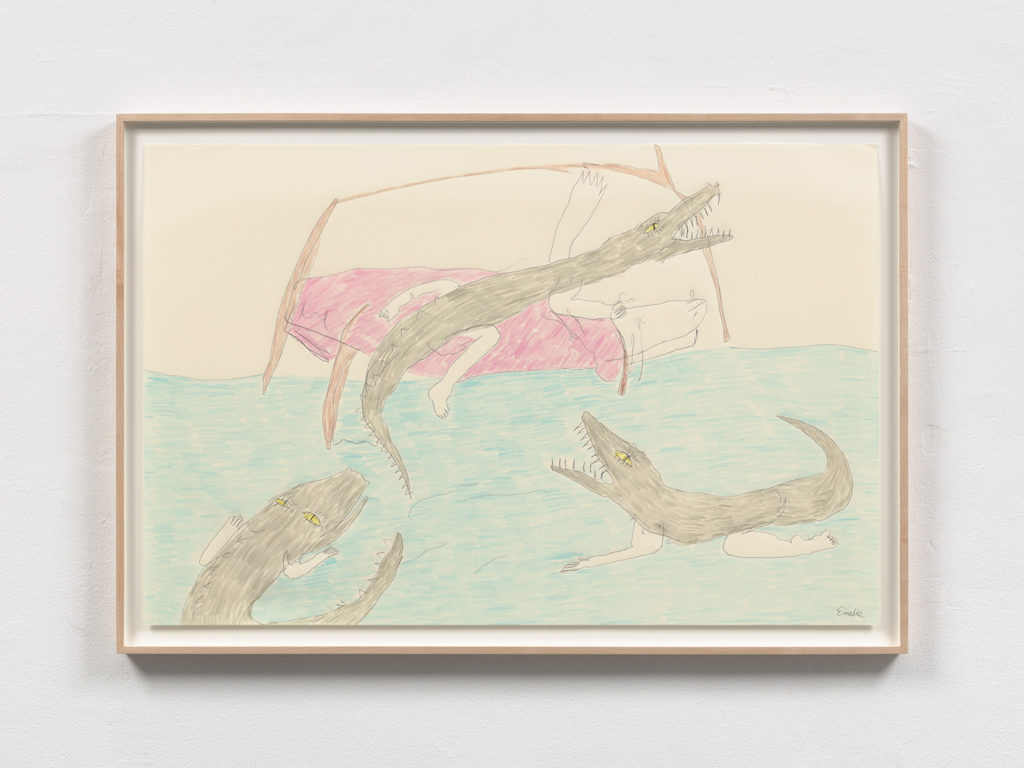

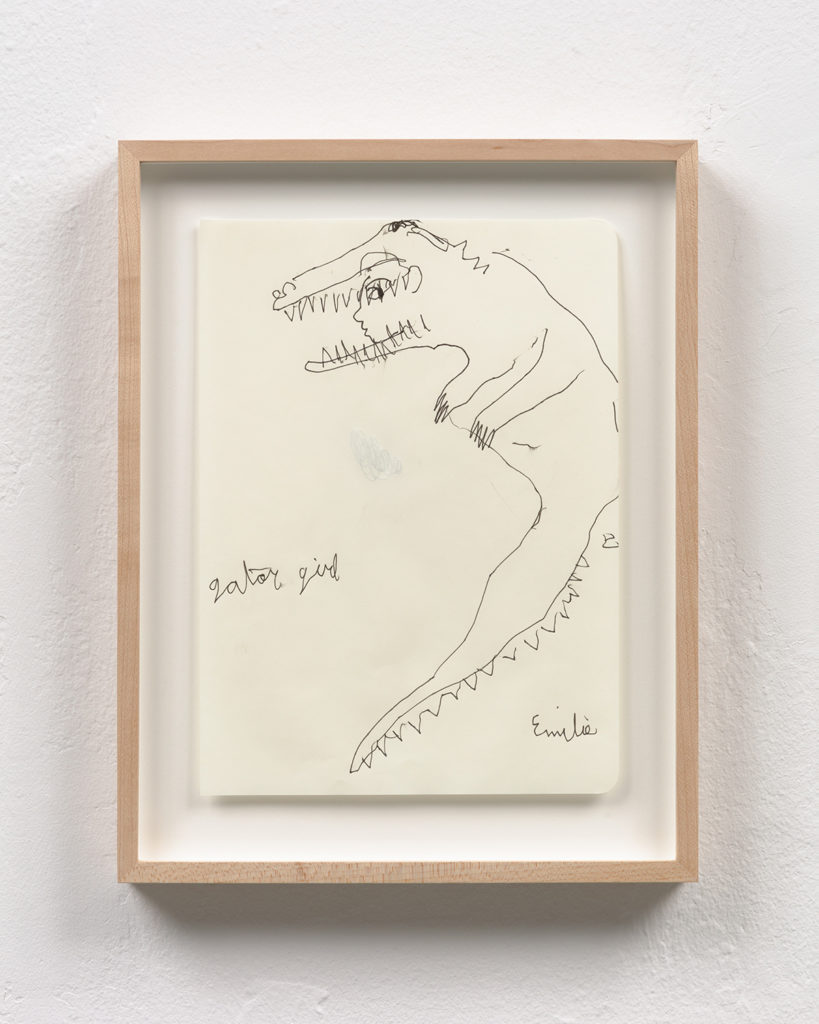

There is a drawing here of Emilie in Louisiana floating down the Mississippi, where two Alligatorgirls and water moccasins with long femme eyelashes swim towards her, beckoning for her to join them. The Sun and the Moon get in each other’s way, a joining of worlds as she rests. On the shore, Gossiaux’s childhood daybed watches as a car is overturned— it seems the landscape will soon consume them both. That same bed appears vitrified in ceramic nearby, while a different sculpted bed has London asleep alone with four- posters of ascending pearlescent orbs. A third shows Emilie and London sleeping beside one another, frozen together en repose.

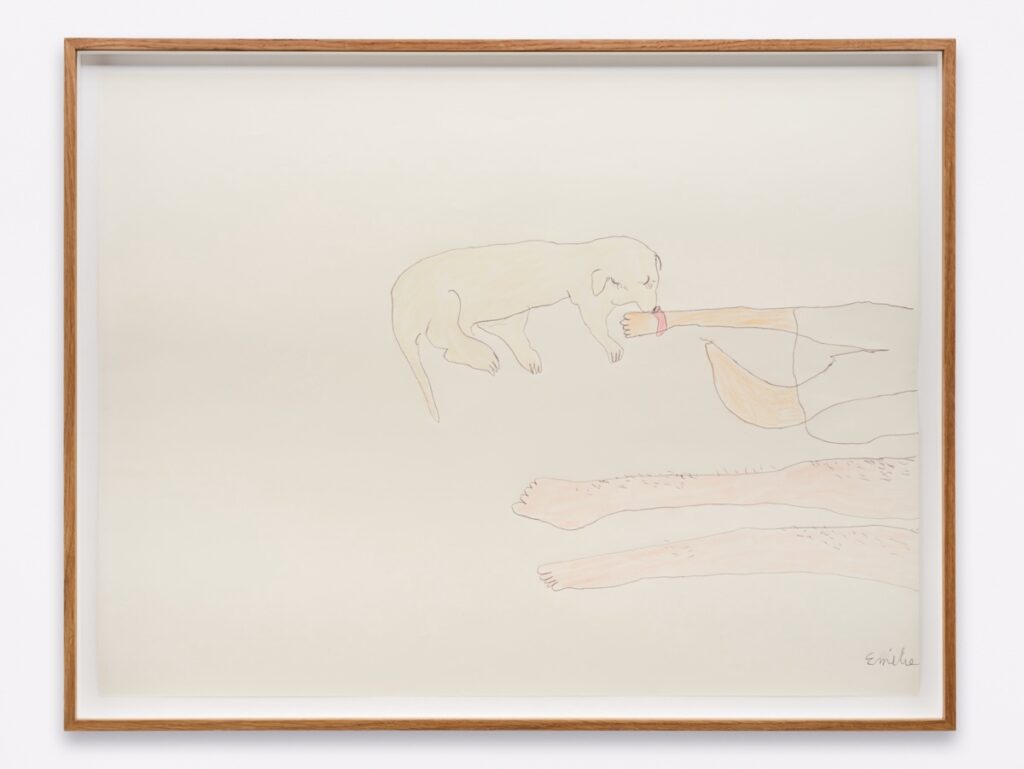

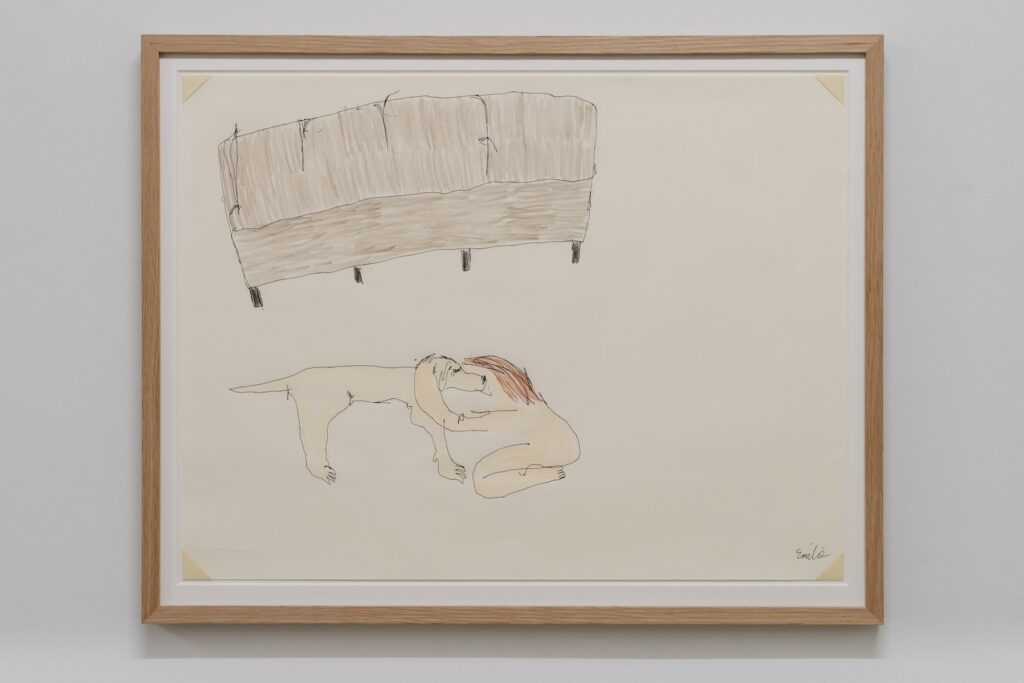

The bed, a place of connection, sets the stage for the exhibition, just as it sets a stage for a spouse, a mother, a daughter—all roles played by London and Emilie interchangeably throughout their time together. For many, a passageway takes the shape of a bed— while the Moon stands watch, the Sun waits to greet you anew. This place, where Emilie and London once returned together day after day, has become the site for a new kind of closeness—that of end of life care. In London’s later life, responsibilities between bodies have changed; she no longer shares the night in the queen-sized bed but rests on a floor-bound cushion throughout the day, attended to by her human-companion in her ever-slowing-pace.

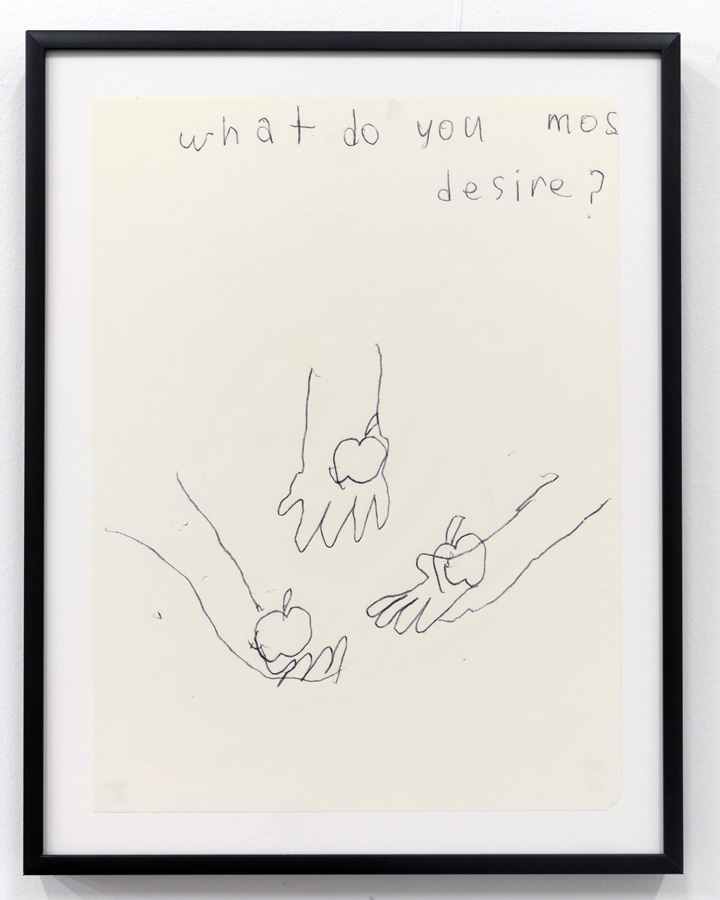

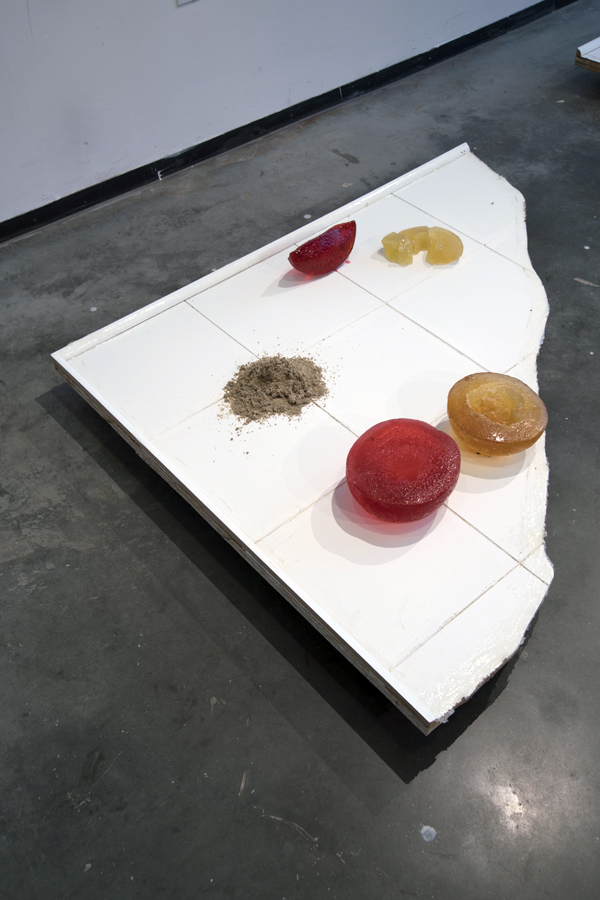

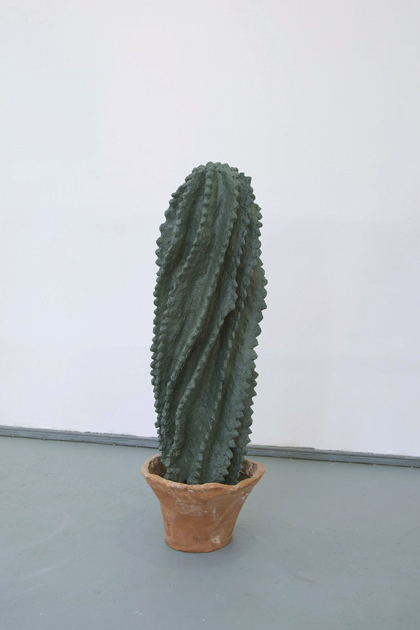

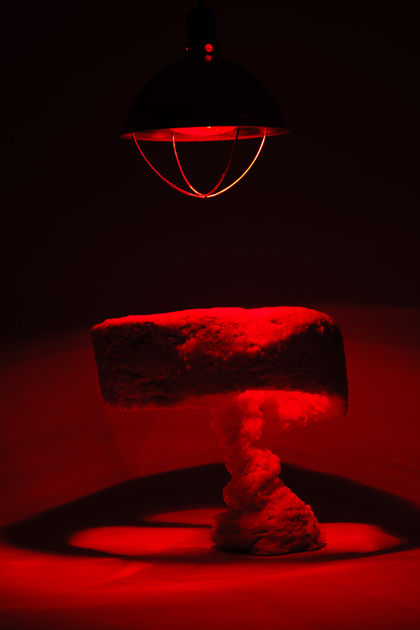

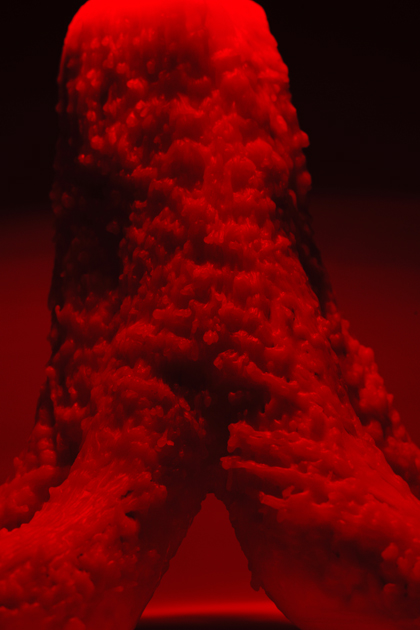

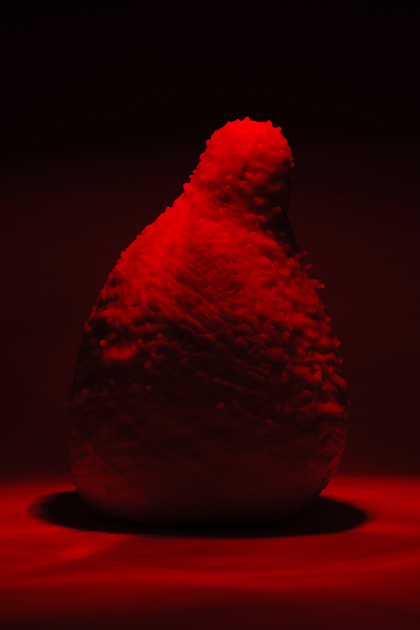

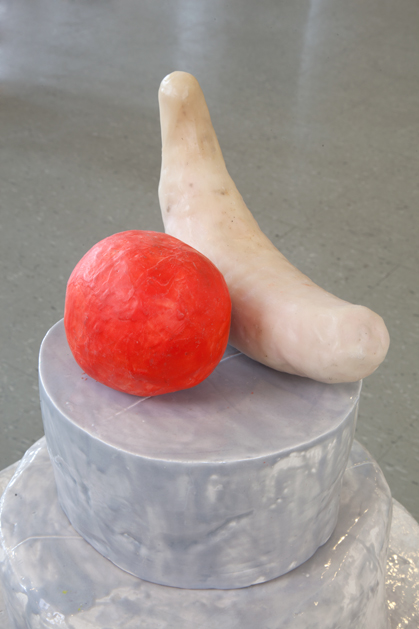

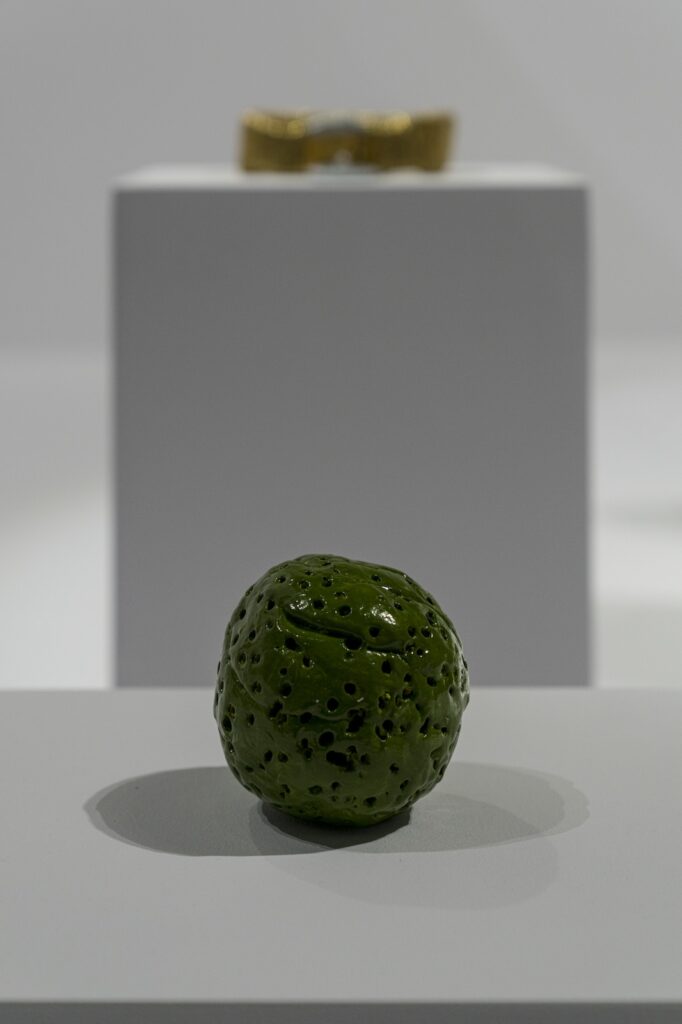

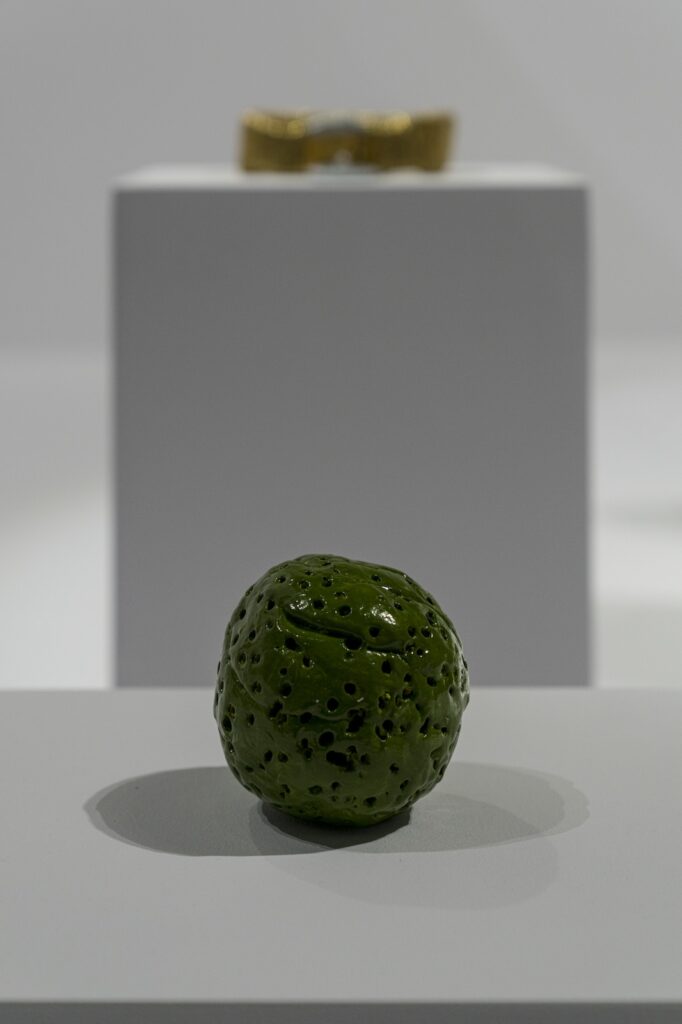

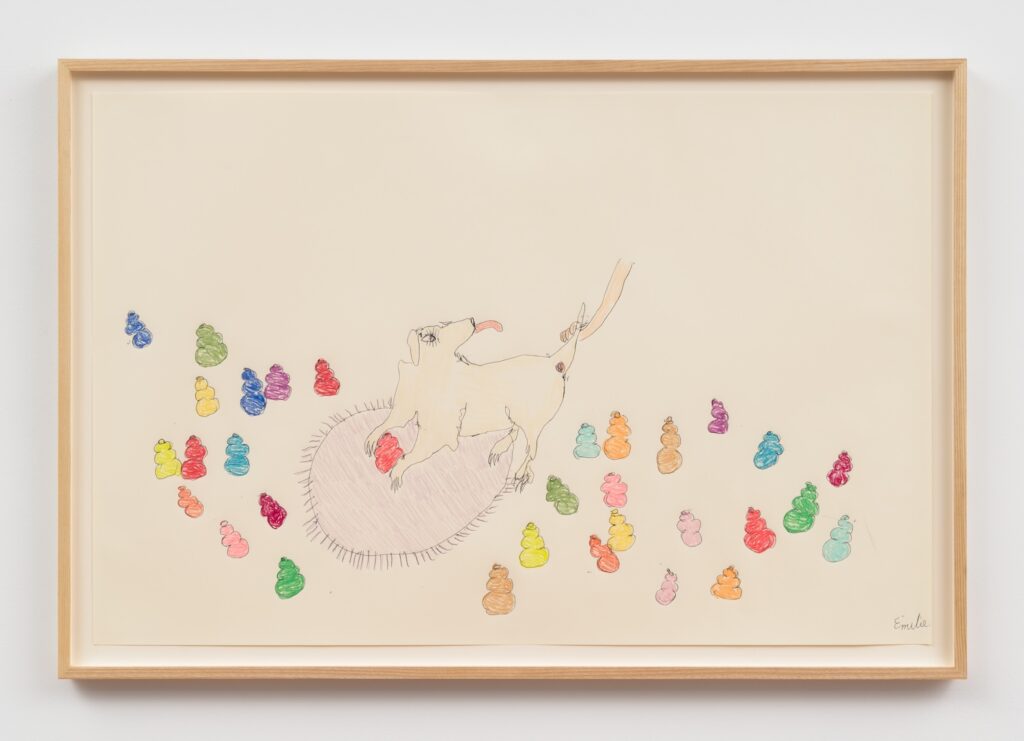

With Kong Play, previously shown at Kunsthall Trondheim, Gossiaux envisions an afterlife for London— where desire finds itself at its most exalted—populated not by a thousand virgins, but rather hundreds of peanut butter filled rubber kongs. With obsession, London chews, chews, chews, licking with incessant vigor, always craving more whilst inhabiting this pleasure palace. Toys durable and subject to play are now rendered earthen and breakable—at once a fragile facsimile and an unshakable monument.

In her notes regarding the exhibition, Gossiaux imagines death as a “second future”. If neither space nor species can dictate the limits of one’s body, then what is death but another river upon which crossings must occur? Infiltration across realms is nothing new; dreams infiltrate the waking and vice-versa. Centers of gravity shift— a kind ghost brushes hair in the morning, and smooths blankets around bodily forms before rest. The caterpillar tucks itself into a cocoon. Traversing technicolor forests, London approaches the crossing and sends a message back.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux: Votives

March 29, 2025 – May 24, 2025

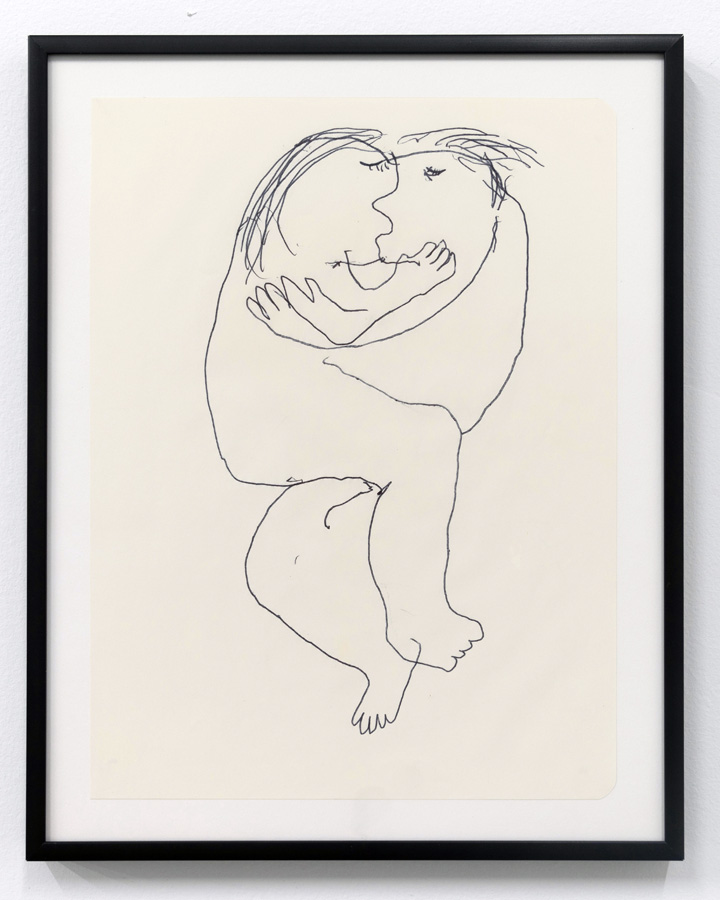

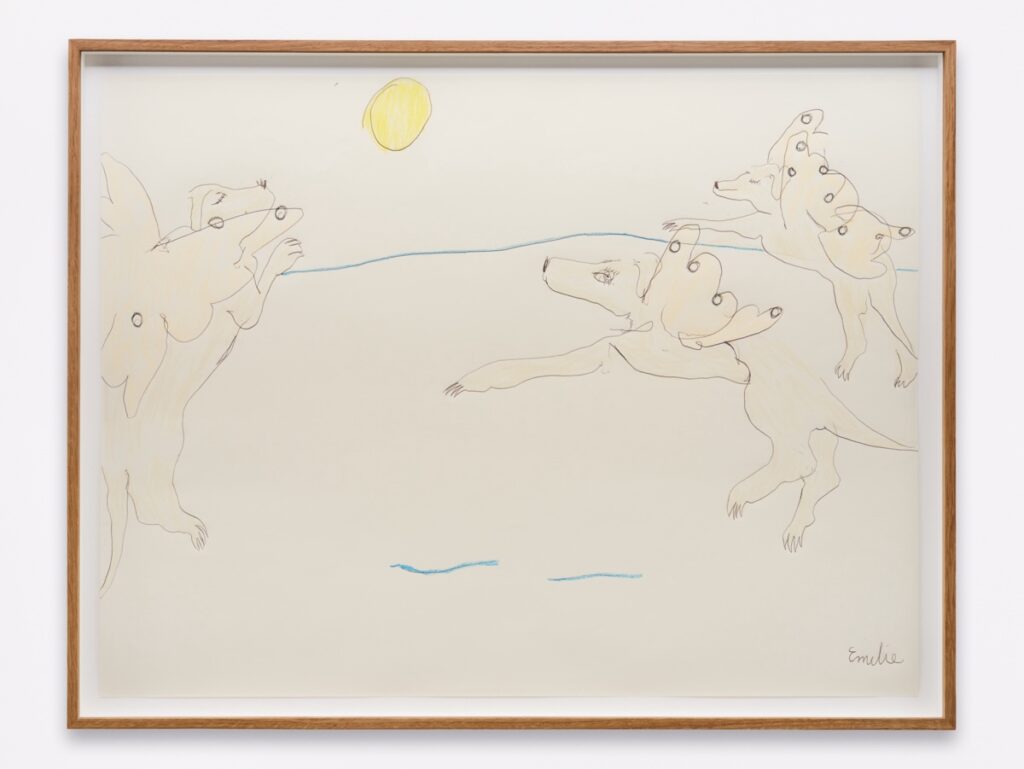

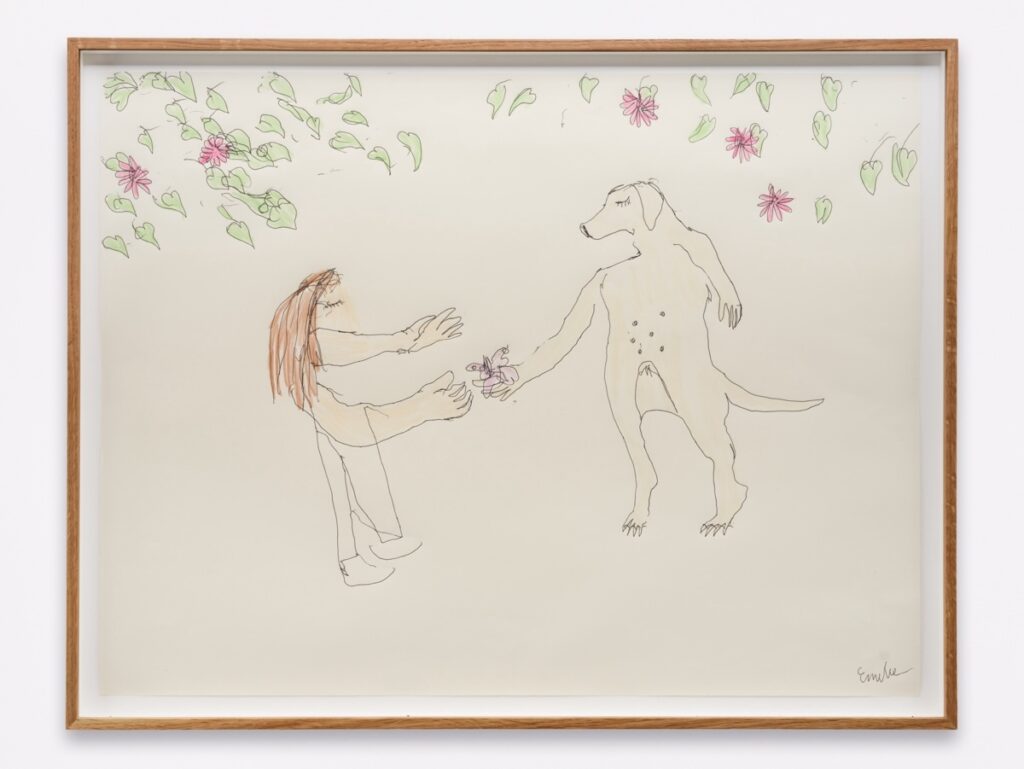

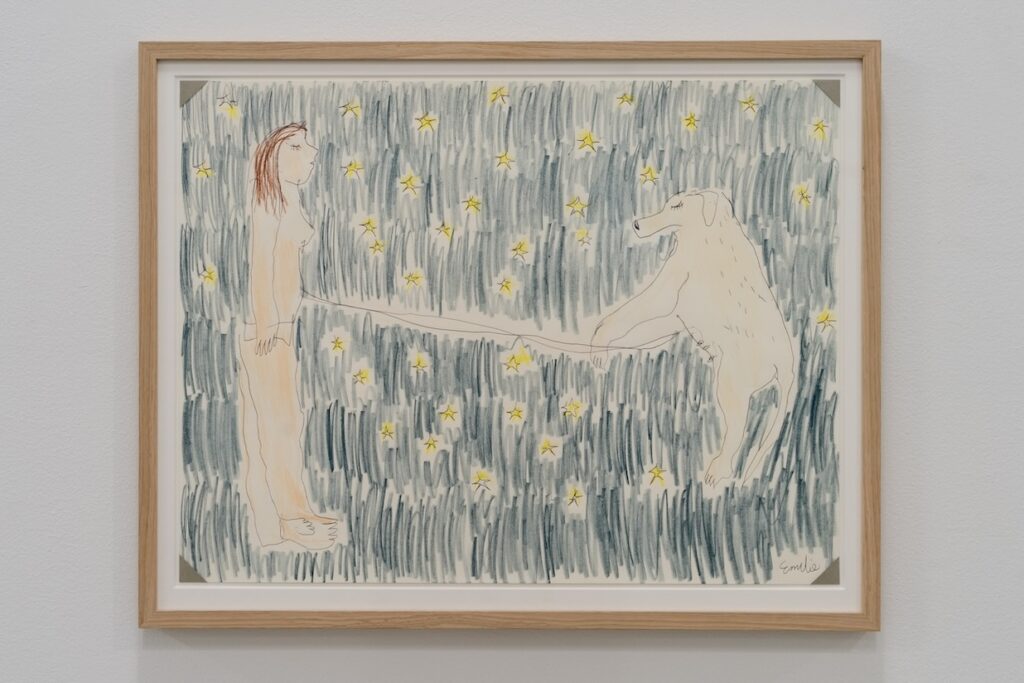

Against a scrim of stars, girl and dog— a specific girl, a specific dog—face one another. Both are bipedal: upright, unattired, similarly scaled, eyes serenely shut. A line unfurls across the middle of the composition to link them belly-to-belly. A leash, an umbilical cord, a sacred ligature: as the particularities of the tie are left open-ended, the fact of the connection—its centrality, its undeniability—feels like a cosmic event.

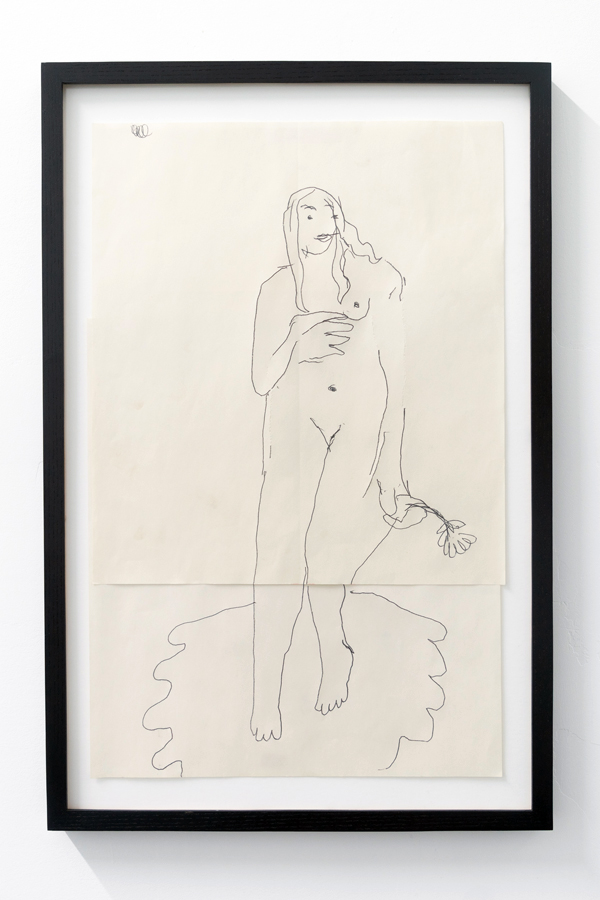

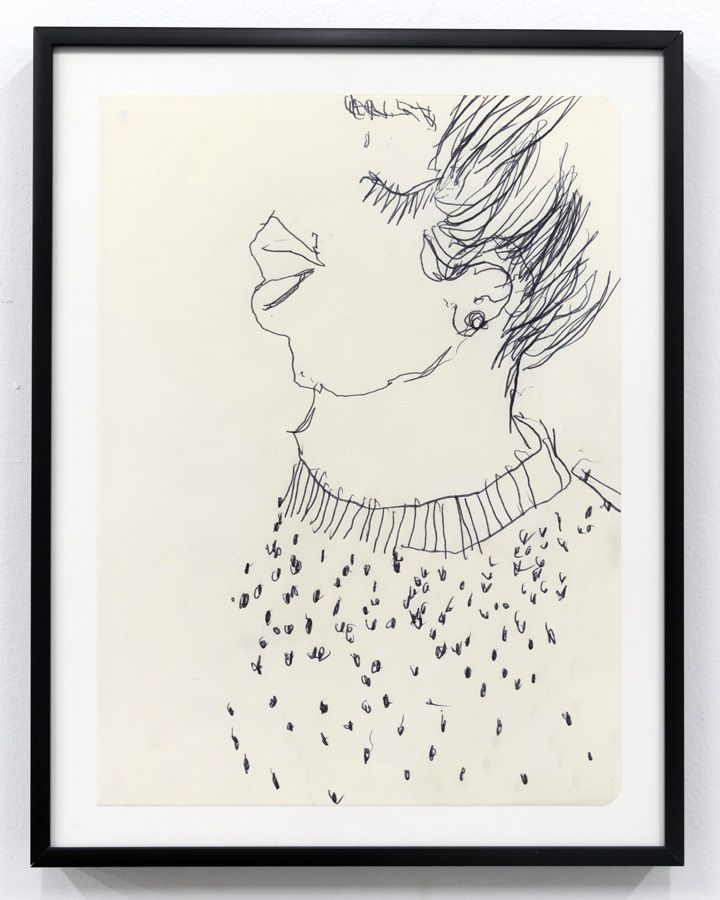

And maybe it is. This ballpoint pen and crayon drawing, Dogs and Humans Figure a Universe (2022), is part of the cosmos of Votives, Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s solo show at CASTLE. Executed using a rubber pad layered beneath the page, with which Gossiaux can feel lines by touch as she moves her pen, the piece depicts the artist with London: a yellow labrador, formerly her guide dog, who is now a senior with reduced mobility.

Featuring drawings and sculptures made in the past five years, including a set of new statuettes, the show sees Gossiaux meditating on her evolving relationship with London as well as broader notions of interdependency and kinship across difference. Tenderly, ferociously, the artist rejects the violent mechanisms that deem certain lives and relationships to be insignificant. This rejection is twofold: Gossiaux challenges the hierarchies that assume human superiority to, dominance over, and separation from animals, while also refusing and subverting the dehumanization or ‘animalizing’ of people with disabilities.

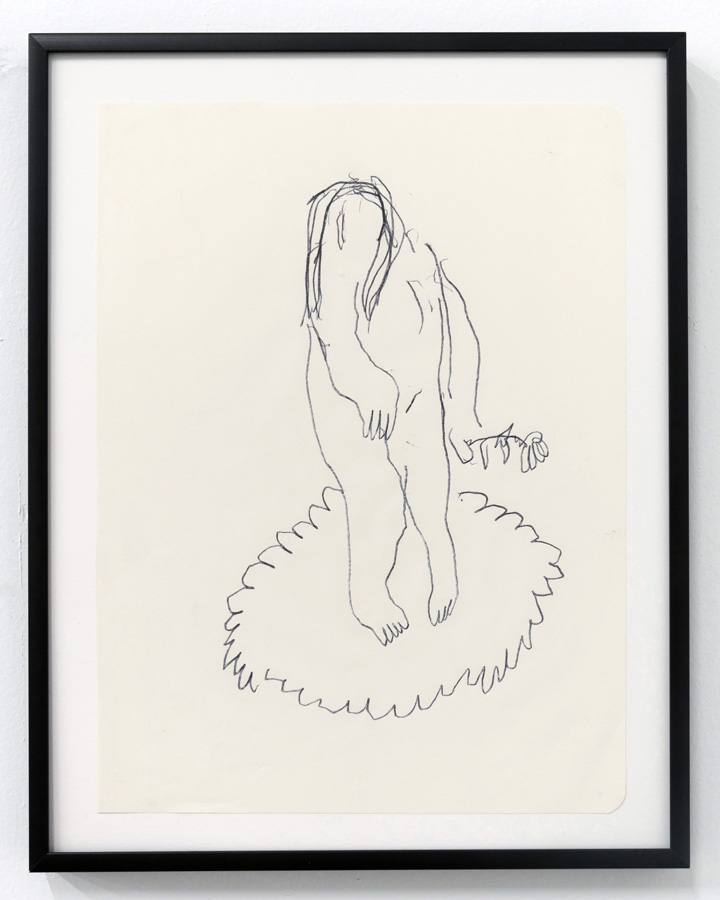

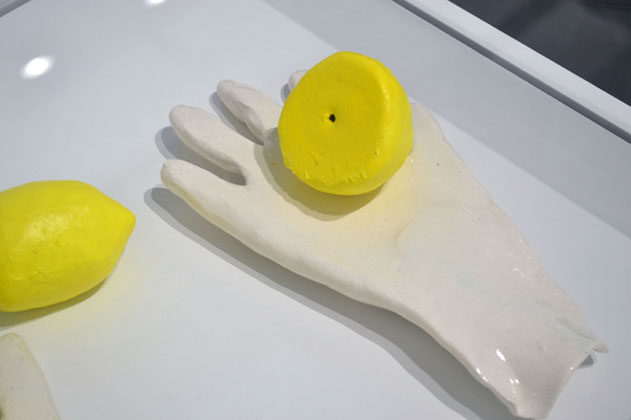

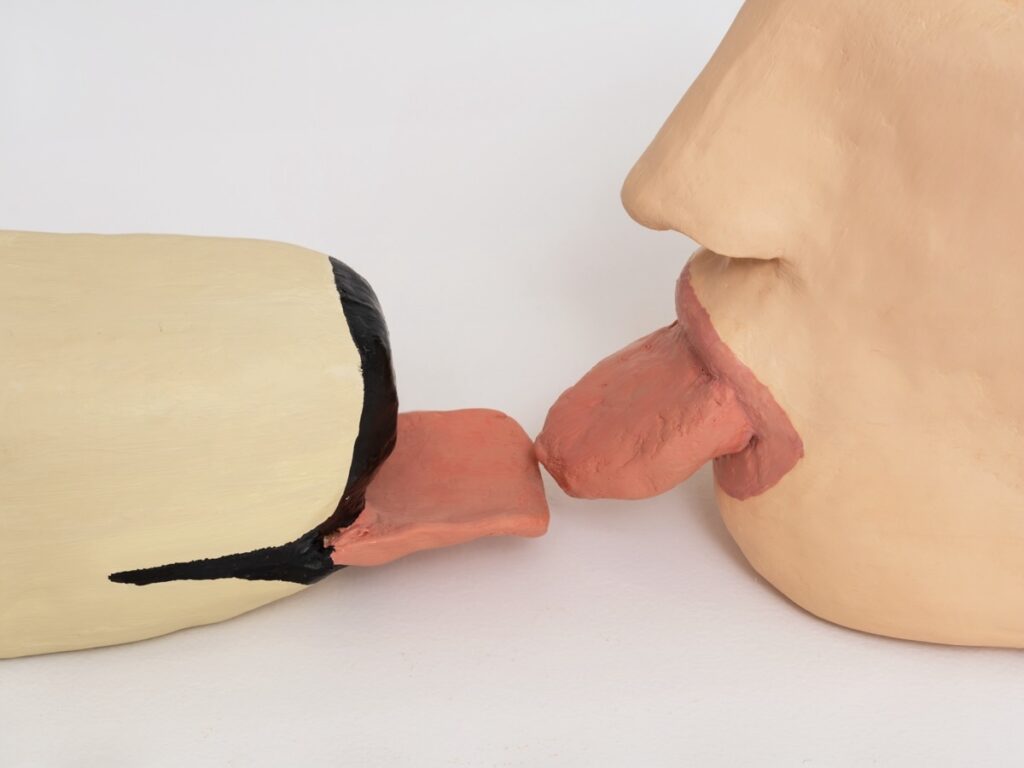

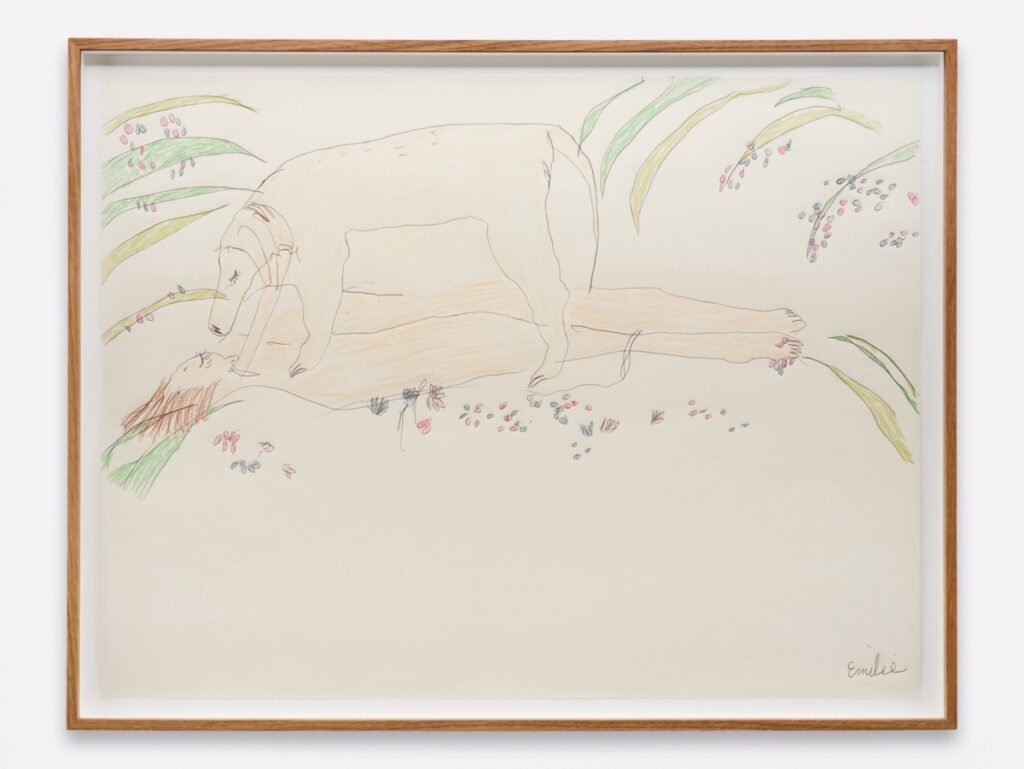

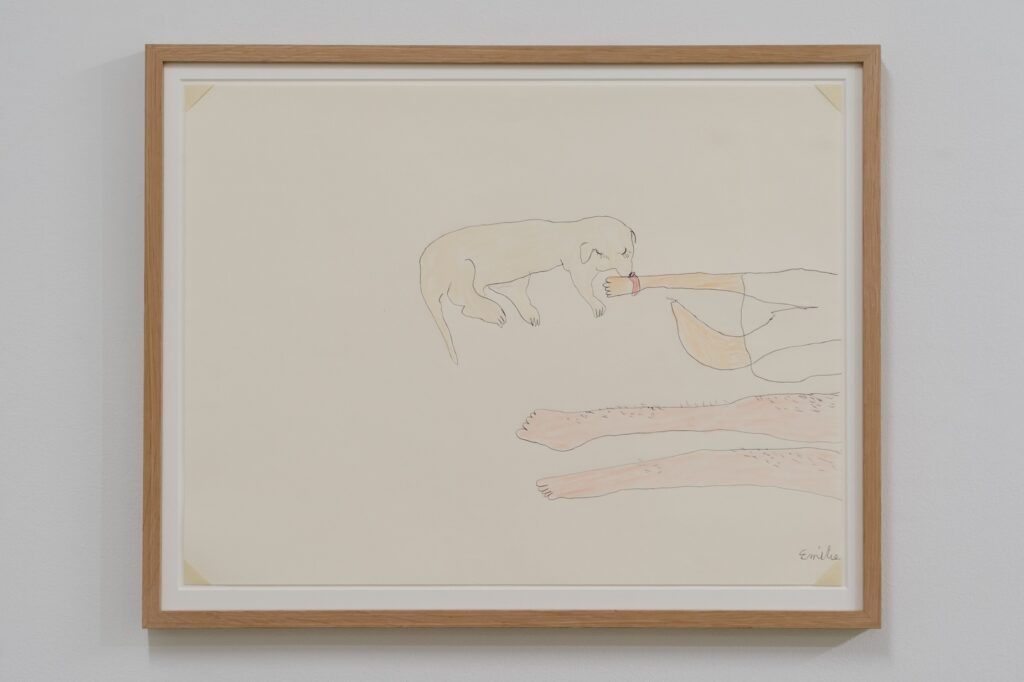

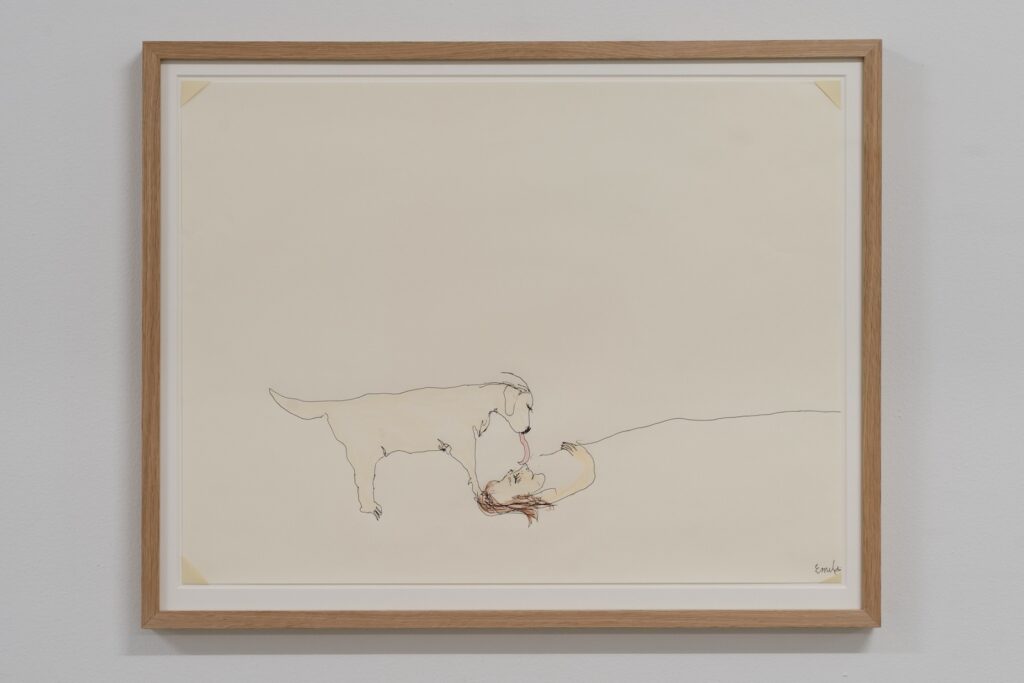

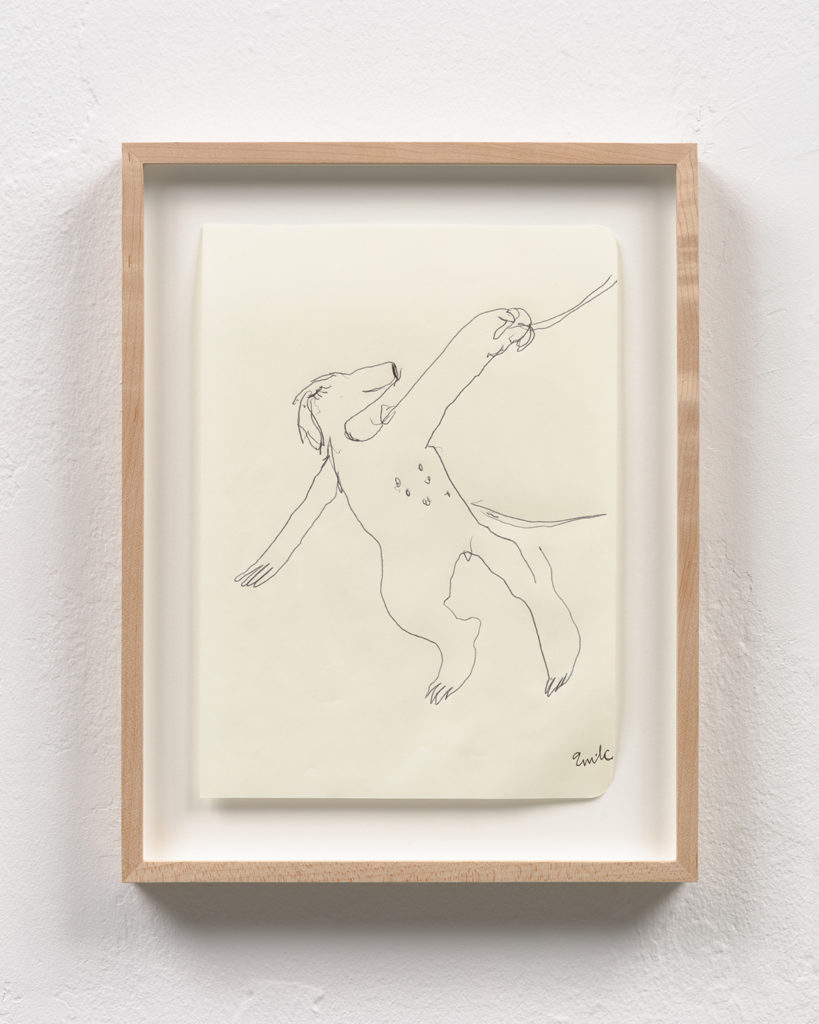

In her work, the line between humans and canines is repeatedly troubled. Dogs adopt humanoid features (or, in a drawing rooted in Gossiaux’s growing interest in animal death rites and afterlifes—London Afterlife [2022]—butterfly wings). People in turn act doglike; subverting the standard order of human-canine greetings, the ceramic sculpture Tongue and Paw (2023) sees a person’s pink tongue extend to lick a paw. This is not to collapse the differences between human and dogs—or purport that companion species relationships are not complicated and even fraught—but to explore a lived, interspecies connection that changes both parties, destabilizing notions of insularity and fixity.

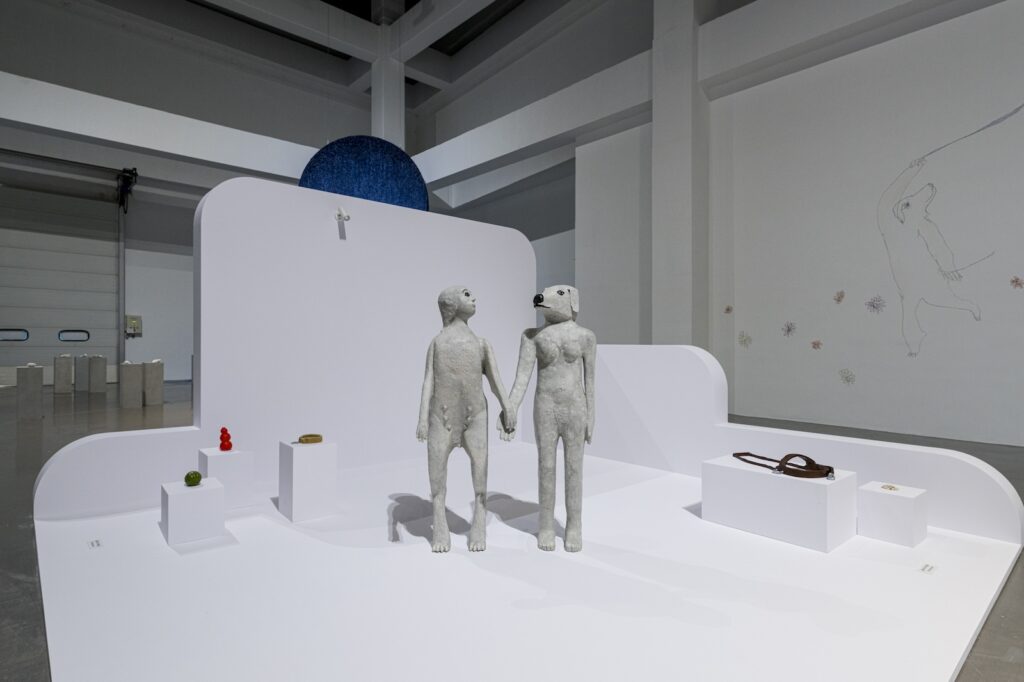

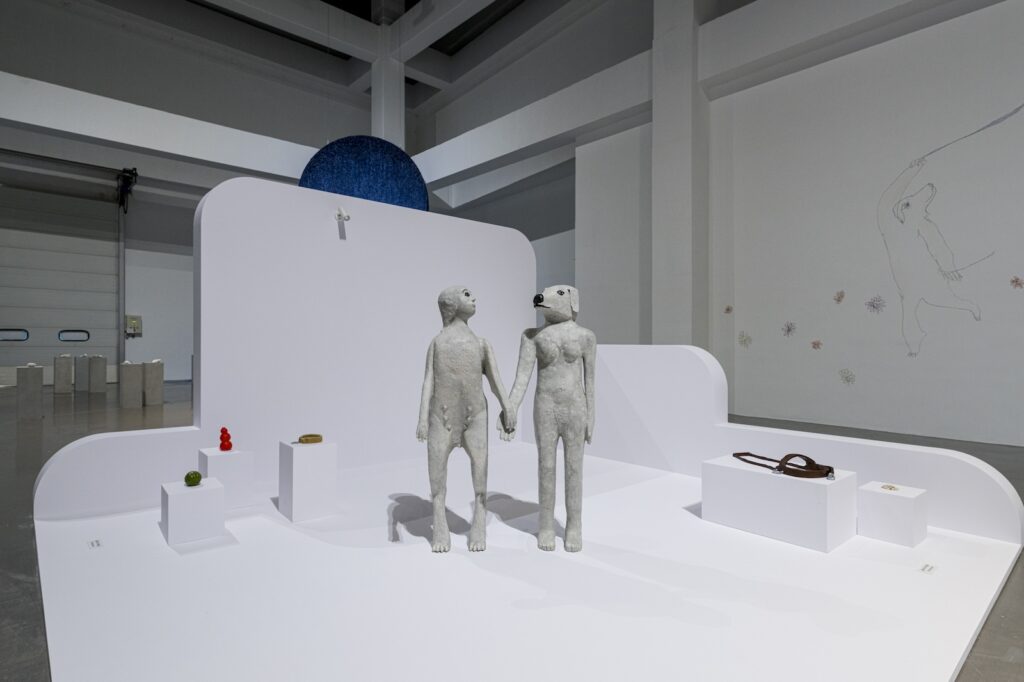

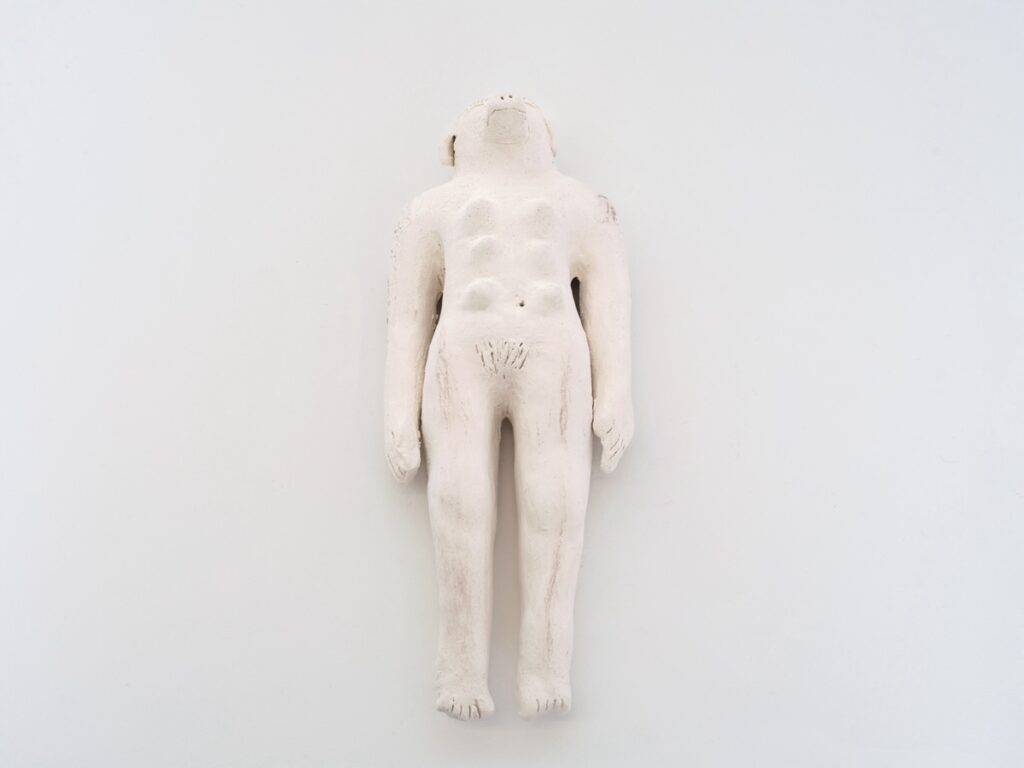

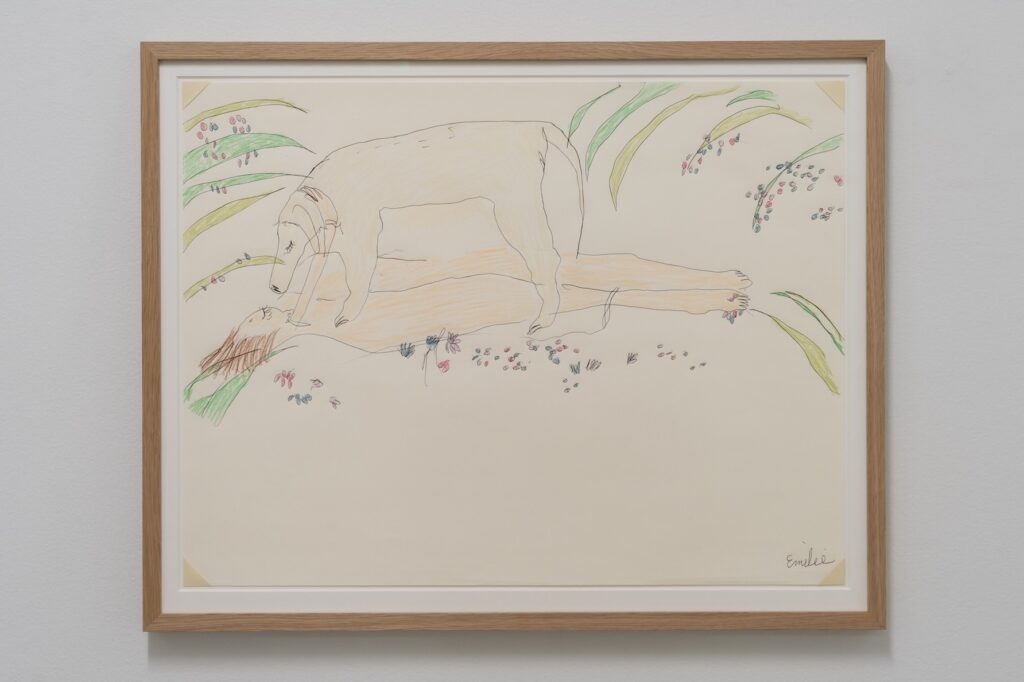

Sometimes, dog and human don’t so much swap—body parts, behaviors, perspectives—as fuse. The Doggirl sculptures—Doggirl, They Called Me (2021), Doggirl (smaller) (2025), and Doggirl (larger) (2025)—each consist of a pale earthenware figure, laid supine, bearing a dog’s head and a woman’s legs. Evoking the potent human-animal hybrids of ancient Egyptian and Greek mythology, the figure suggests a multispecies assemblage wherein the whole indubitably exceeds its parts. Such thinking chimes with Gossiaux’s formulation of a “super-being”: a term she uses, counter to ableist frameworks, to describe her and London’s combined powers. Interdependency—between and beyond humans—isn’t just a fact of existing within a larger ecology; it’s a wellspring.

–Cassie Packard

Have you ever had someone depend entirely on you? Or have you ever depended entirely on someone else? Kinship, an exhibition at Kunsthall Trondheim, joyfully captures these deep connections through the story of an artist and a dog. Featuring drawings, sculptures, and a newly commissioned installation of one hundred ceramic objects spanning two gallery floors, Kinship invites reflections on your own interdependence with others while embracing your animal self.

Artist Emilie Louise Gossiaux first met London, a blonde English Labrador Retriever, the day after her 24th birthday. Born three years earlier, London entered Emilie’s life just two months after a traffic accident caused Emilie’s blindness. Since then, for over a decade, London has been not only Emilie’s guide dog, but also a close companion and muse.

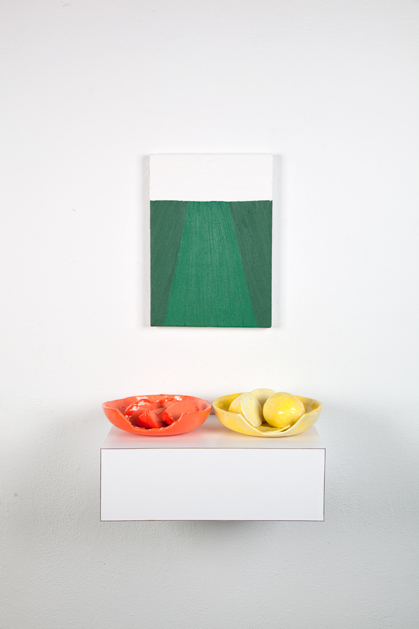

In Kinship, visitors follow a trail of multicolored ceramic sculptures of various sizes, inspired by the design of “Kong” chew toys—snowman-like rubber structures made of stacked spheres and often used to hold doggie treats. Along this trail, a survey of the artist’s work is presented through a series of vignette-like displays. From one to the next, sculptures and drawings chart the interplay of Emilie and London’s lives and bodily forms to celebrate their shared experiences. Together, they form a unified whole—a super-being that transcends hierarchical boundaries.

Beyond honoring these bonds, Kinship challenges the distinctions between non-disabled and disabled individuals, as well as between humans and animals, by highlighting our mutual interdependence and co-evolution. These themes respond to Emilie’s personal experiences of dehumanization and discrimination while traveling with London. Instead, Kinship opens new perspectives that foster greater empathy and respect for both animals and “Crip” individuals. It encourages a rethinking of how we engage with other species and highlights the need for inclusivity and recognition of diverse forms of life.

To meet these calls, Emilie infuses her work with a profound sense of disability pride and the morality of animal rights. She addresses the intersection of disability activism with animal welfare, emphasizing that the treatment of nonhuman beings often reflects broader societal attitudes toward disability. The sensory quality of the artist’s pieces, crafted through memory and touch, encourages viewers to experience art in an unconventional way, reflecting the tactile connection the artist has with London. Every drawing and sculpted form becomes a celebration of their shared journey, making Emilie’s art a testament to the beauty of connection and to the unspoken, species-transcendent language of love and trust.

In a first for Kunsthall Trondheim, the gallery will offer both audio descriptions, and a braille guide for this exhibition, which is the artists first European solo-show.

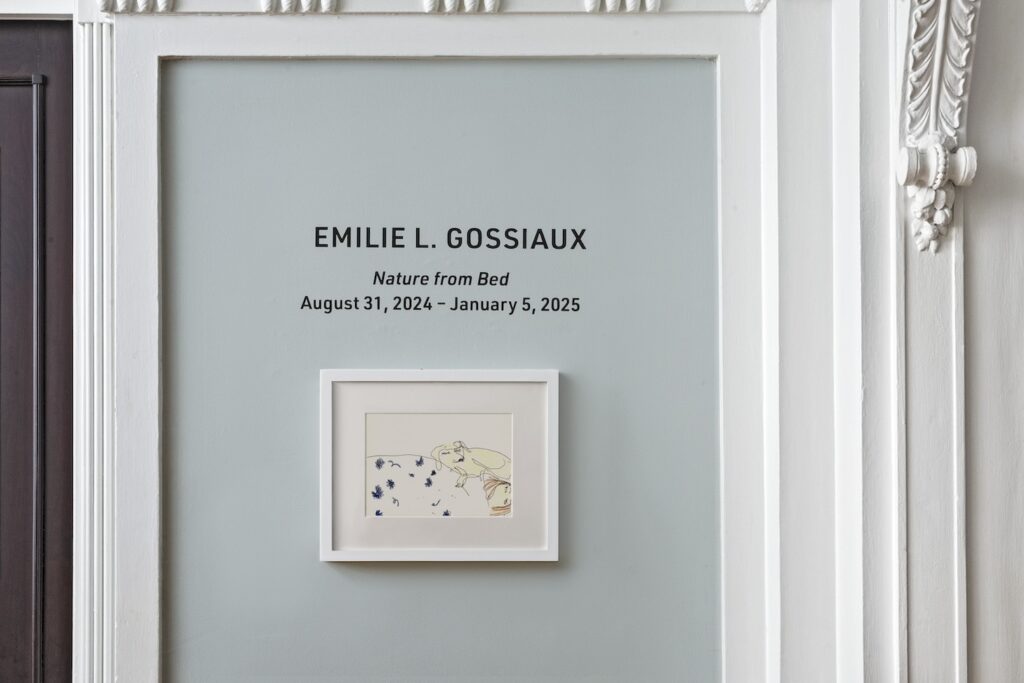

Emilie Louise Gossiaux

Nature from Bed

Wave Hill House

August 31, 2024 – January 5, 2025

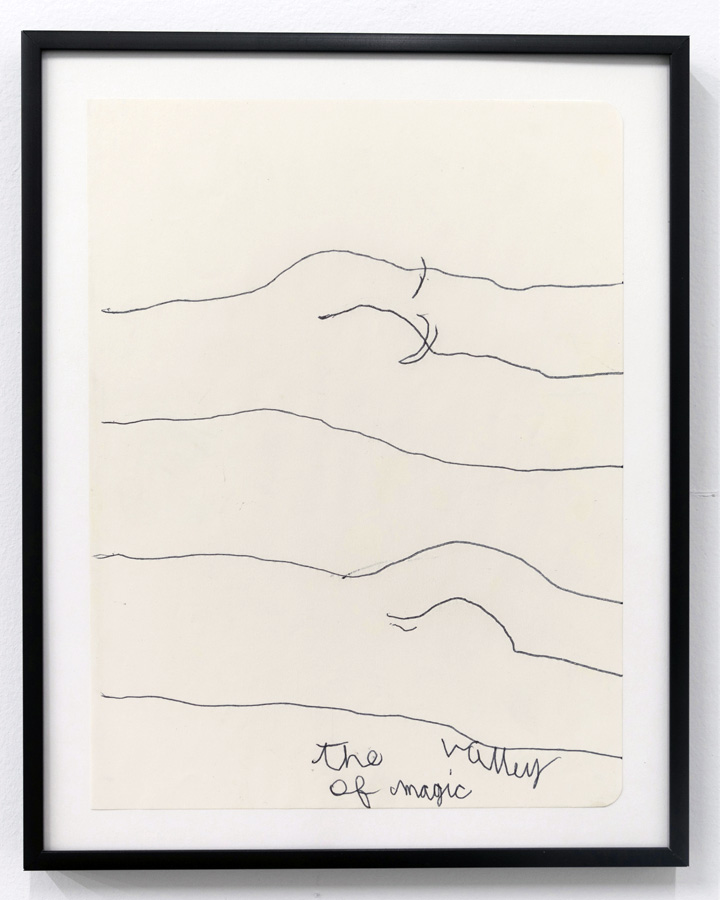

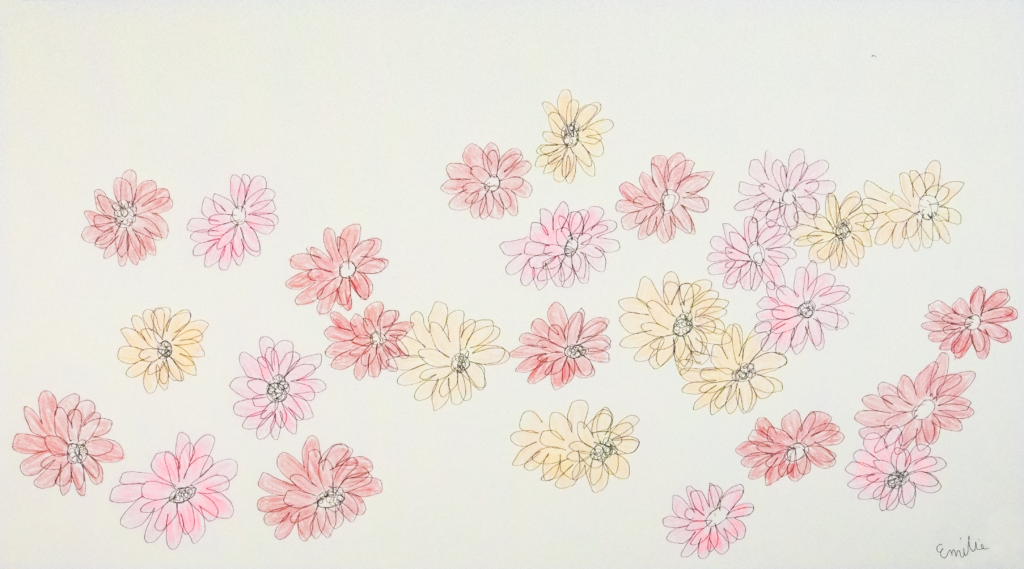

Having lost her vision in 2010, Gossiaux’s experience of nature doesn’t always take place outdoors. In fact, she often accesses the outdoors from her bed. For example, as a Winter Workspace artist-in-residence at Wave Hill in 2021, Gossiaux encountered the gardens primarily through detailed verbal descriptions provided by one of the curators. Whether listening to audio recordings, dreaming of plant-human hybrid bodies, or cuddling with London—her guide dog and close companion—under her floral bedspread, Gossiaux does not need to be outside to feel at one with nature. Her work illustrates that physical and imaginary walls cannot delineate nature and wildlife from our day-to-day existence. In this way, Gossiaux’s drawings are guided by tactile sensation, taking on a highly intimate quality both in subject matter and form. The artist uses ballpoint pen and crayon to feel her lines as she works. Using playful marks and bright colors, images of hummingbirds licking the inside of human ears create a visceral sensory experience for the viewer that brings us closer to both our natural surroundings and the artist’s experience of the world. In doing so, Gossiaux invites viewers to move beyond human-centrism and imagine modes of life in which people and non-human species share an interdependence. As a result, new forms of kinship and ways of relating to each other emerge as central to Gossiaux’s work.

Emilie L. Gossiaux: Nature from Bed is organized by Afriti Bankwalla, Curatorial Administrative Assistant, with Gabriel de Guzman, Director of Arts and Chief Curator, and Rachel Gugelberger, Curator of Visual Arts.

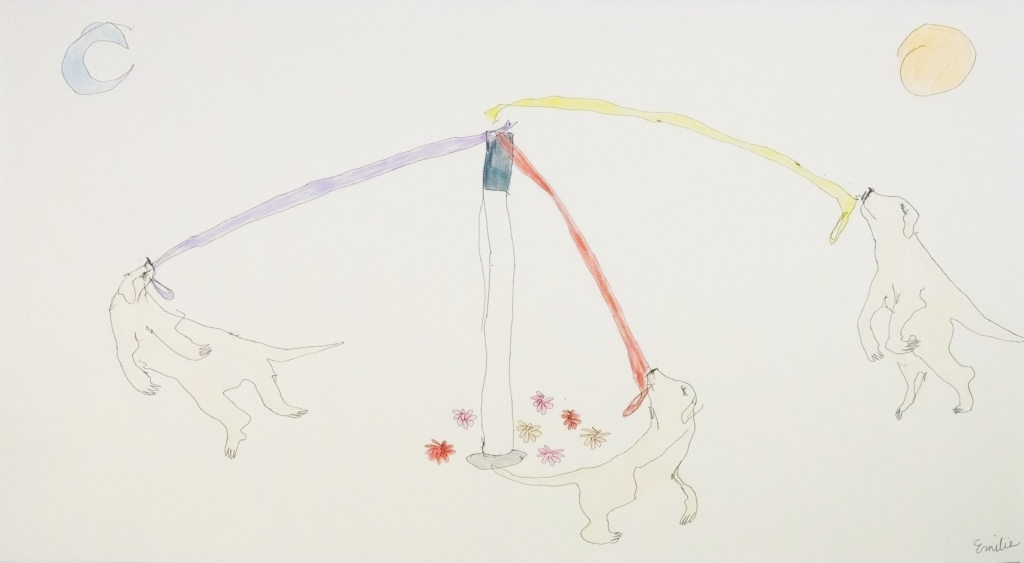

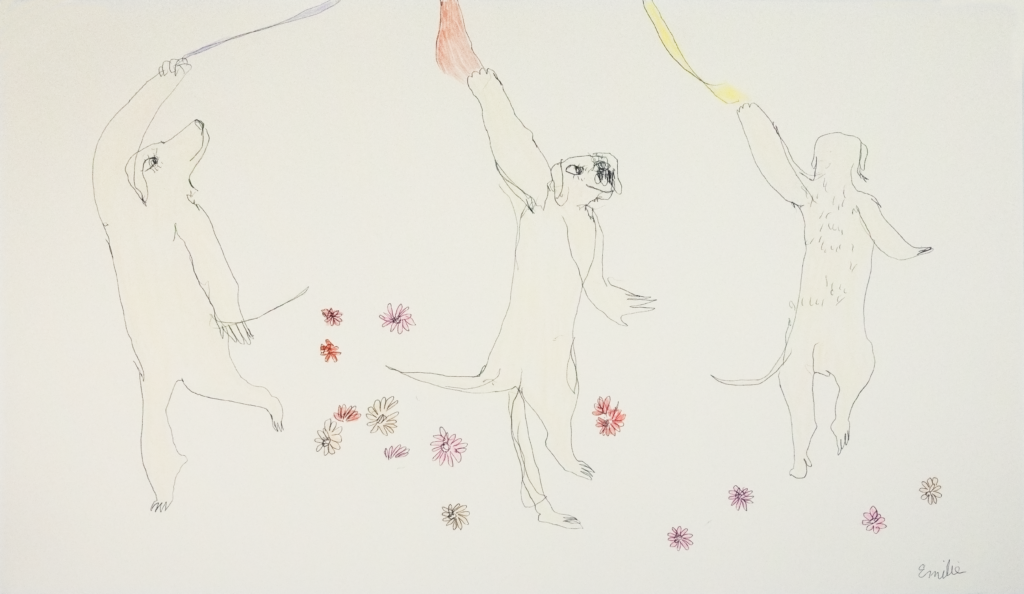

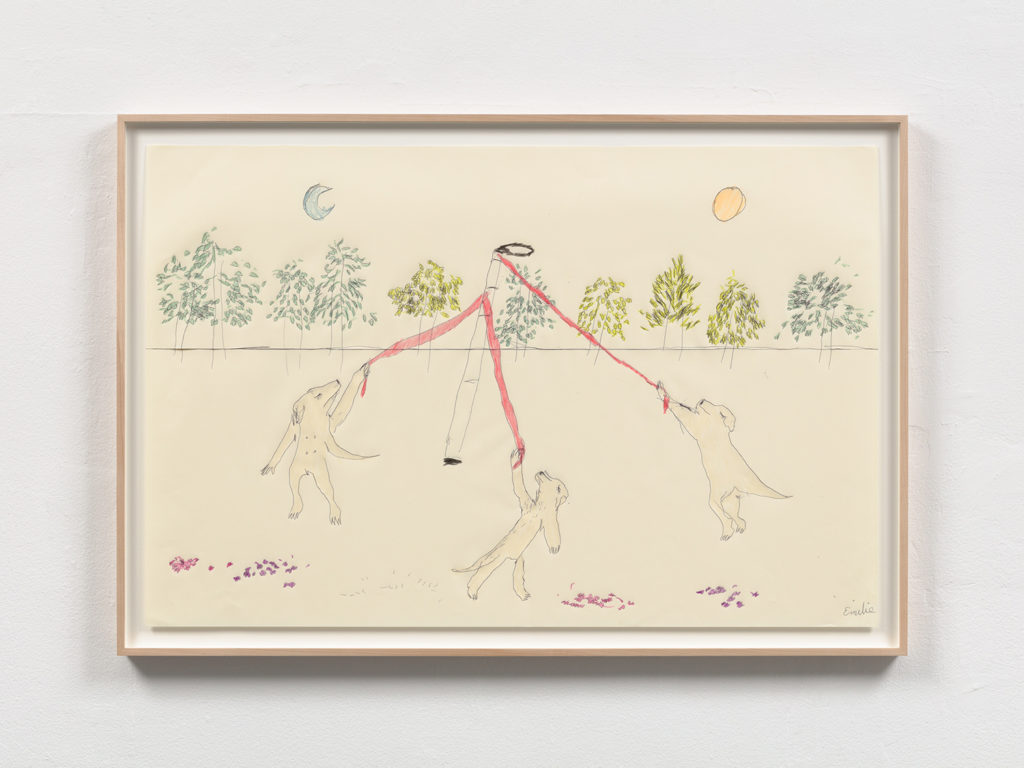

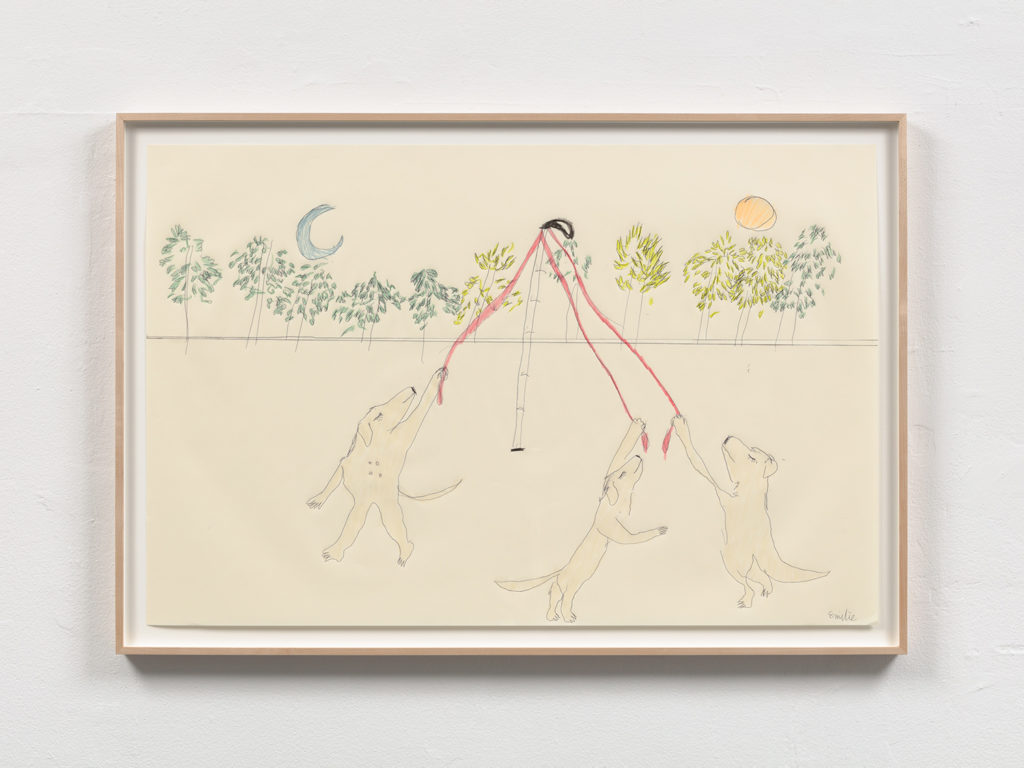

Our world is overwhelmingly centered around non-disabled humans. Rather than this singular overruling perspective, what if unity was co-built across species and disability status? Emilie L. Gossiaux constructs such a world, bringing to life an image from her imagination of her guide dog London dancing around a white cane maypole. Borrowing the phrase “other-worlding” from feminist scholar Donna Haraway in conceiving a just society that operates outside of hierarchies, Gossiaux proposes an alternative to the intertwined systems of capitalism and ableism that oppress humans and animals. In opposition to repressive structures, the artist’s fantastical installation and three related drawings render scenes of joy, liberation, and love.

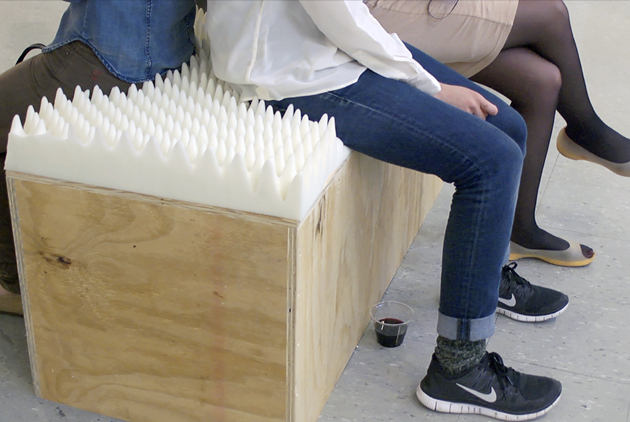

Central to this exhibition is the white cane. A tool used by blind and low-vision individuals, the white cane is also a symbol of freedom. Here, Gossiaux transforms the white cane into a glistening maypole towering at 15 feet tall, three times the size of her own. Paying homage to the white cane, the artist plays with scale to emphasize its importance in providing agency and independence, bestowing it with a much-deserved larger presence and societal awareness.

The artist also creates a space of independence for London, her guide dog, who is transformed here into a woman-sized dog. Melding human and dog together, Gossiaux expands upon their interspecies relationship that is at once interdependent and liberating. The three Londons are unconstrained by the leashes that normally restrict them. Instead, they hold the leash handles in their hands, empowered to move at their own pace.

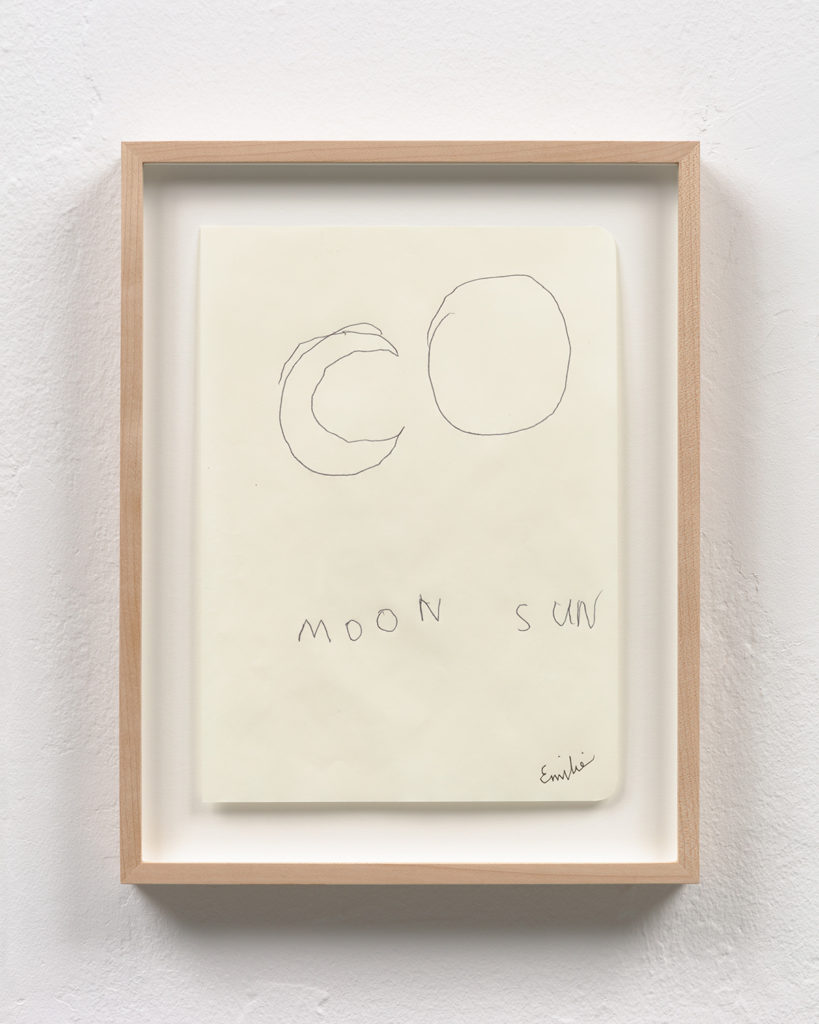

Across this exhibition, elements of fantasy – dog-women, concurrently shining moon and sun, and a giant white cane – work together to amplify disability joy, autonomy, and a love that transcends boundaries. By immersing us in a dreamlike terrain, Gossiaux invites us to “other-world” with her.

Emilie L. Gossiaux: Other-Worlding is organized by Sarah Cho, Assistant Curator.

Press Release: https://mothergallery.art/significant-otherness

Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s solo exhibition Significant Otherness consists of ceramic sculptures and pen-and-crayon drawings that consider interspecies bonds to transcend conventional hierarchies between humans and nonhuman species. Mirroring the exhibition title, the phrase “significant otherness” originates from feminist scholar and theorist Donna Haraway’s Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People and Significant Otherness in which the writer deftly explores relational encounters between humans and nonhuman species bonded in their significant otherness, or a complex recognition of difference. Haraway also riffs on the popular phrase “significant other” to claim kinship across species, particularly between humans and dogs, just as Gossiaux does within her own artistic practice. Centering her own interspecies relationships throughout the exhibition, Gossiaux describes her nine-year relationship with her golden Labrador retriever and guide dog, London, as one that is simultaneously practical, spousal, maternal and emotional. In a new artistic exploration, Gossiaux also finds solace in connecting with an unlikely species—the alligator.

Gossiaux presents new earthenware ceramic pieces as an homage to London’s life. She recreates objects of personal significance associated with London’s everyday work routine, playtime, and pleasure, such as rubber chew toys of various shapes, her collar and name tag, harness, and leash. Dog collars, harnesses, and leashes serve as bodily extensions that mutually and physically connect dog to human and human to dog. In contrast to the objects associated with the working aspects of London’s life as a guide dog, the artist also recreates a favorite bulbous chew toy, whose interior is often stuffed with thick globs of peanut butter as a treat to lick, in turn, giving the object a sensual dimension. In this collection of nostalgic memorabilia, Gossiaux honors seemingly quotidian objects that nurture and shape shared intimacies between dogs and humans.

Gossiaux also debuts three extraordinary ceramic human-animal hybrid figures, which each occupy distinct postures and physical characteristics. In her titles for Dreaming Doggirl, Doggirl, and Alligatorgirl, she creates compound words to further hybridize the language she uses to describe her figures. Native to the three million acres of wetlands in and around New Orleans, where Gossiaux is also from, the alligator becomes her alter ego, a feminist embodiment to express feelings of anger or frustration. In the sculpture Alligatorgirl, the creature’s jaws are wide open, revealing a human’s expressionless face surrounded by sharp jagged teeth, just before she devours the body whole. In Alligatorgirl Riot, Gossiaux draws yellow-eyed reptilian creatures with human limbs and alligator bodies swimming together, with the exception of one of them vigorously climbing out of the water and crawling into a human’s bed. With the known, persistent threat of climate change to the alligator’s wetland habitat as a result of the irresponsible ways we humans have treated our environment, Gossiaux’s Alligatorgirl works subtly allude to a future where the animals might turn even more aggressive, especially when feeling threatened.

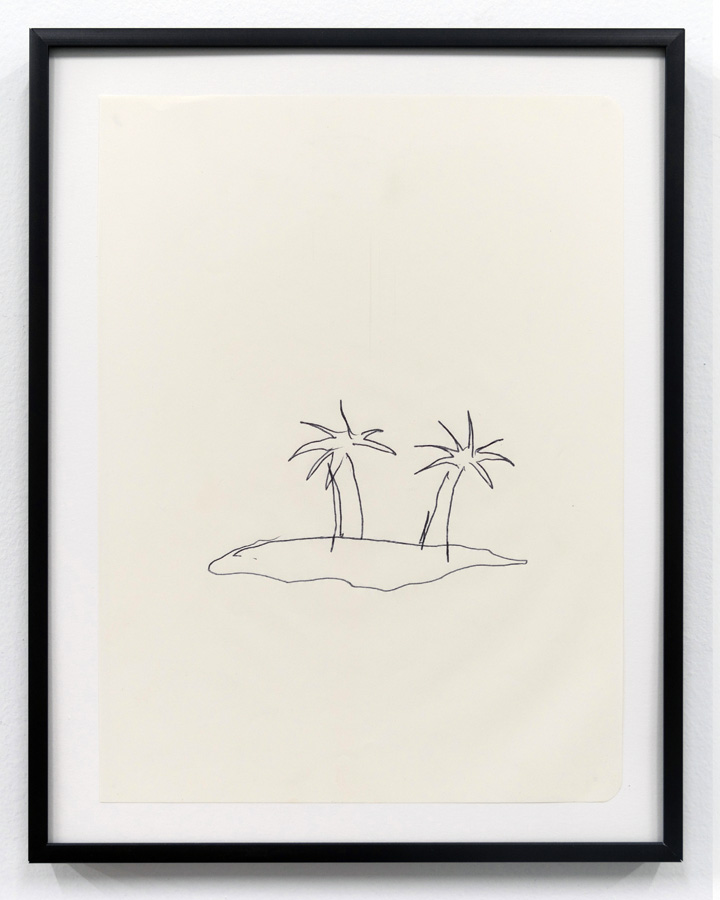

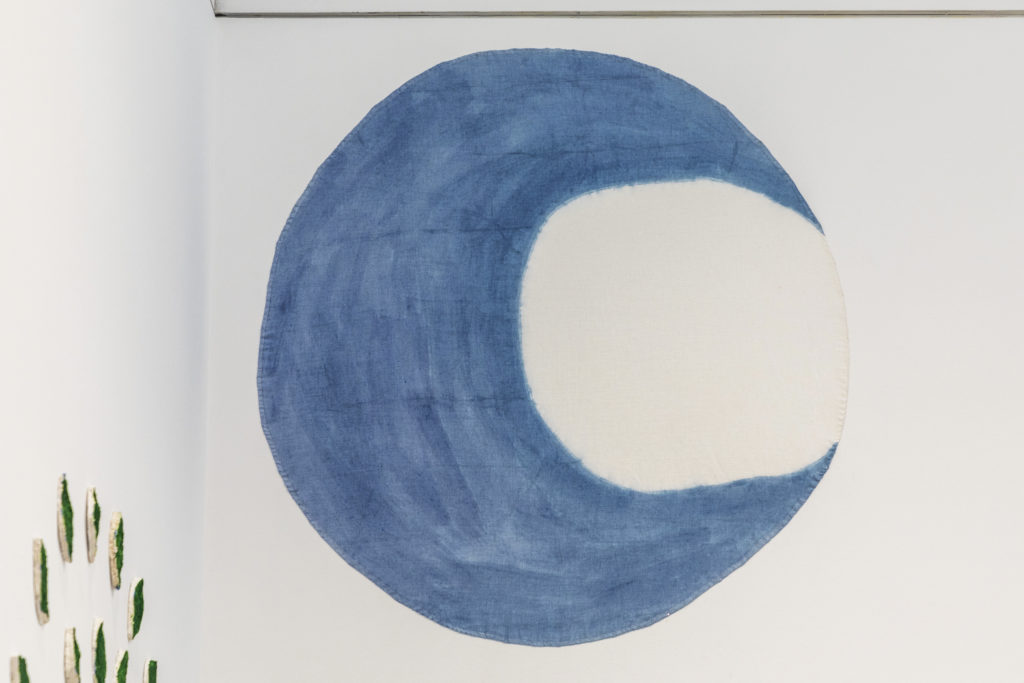

In addition to her work exploring interspecies relationships, Gossiaux depicts other forms of mutual coexistence in her drawings, which she creates either from memory or through touch, as with her sculptures. In Moon and Sun, Gossiaux draws a crescent moon and sun, positioned side by side, both taking up equal space in the sky. We often think of the sky as dominated by either the sun or moon depending on the time of day; however, their coexistence is a common occurrence. This drawing serves as a compelling connection to Gossiaux’s other bodies of work that propose alternative ways we as humans can exist with and among other beings, together in our significant otherness.

—Alessandra Gómez, April 2022

Emilie L. Gossiaux | Memory of A Body

December 12 – February 20, 2021

Curated by Emily Watlington

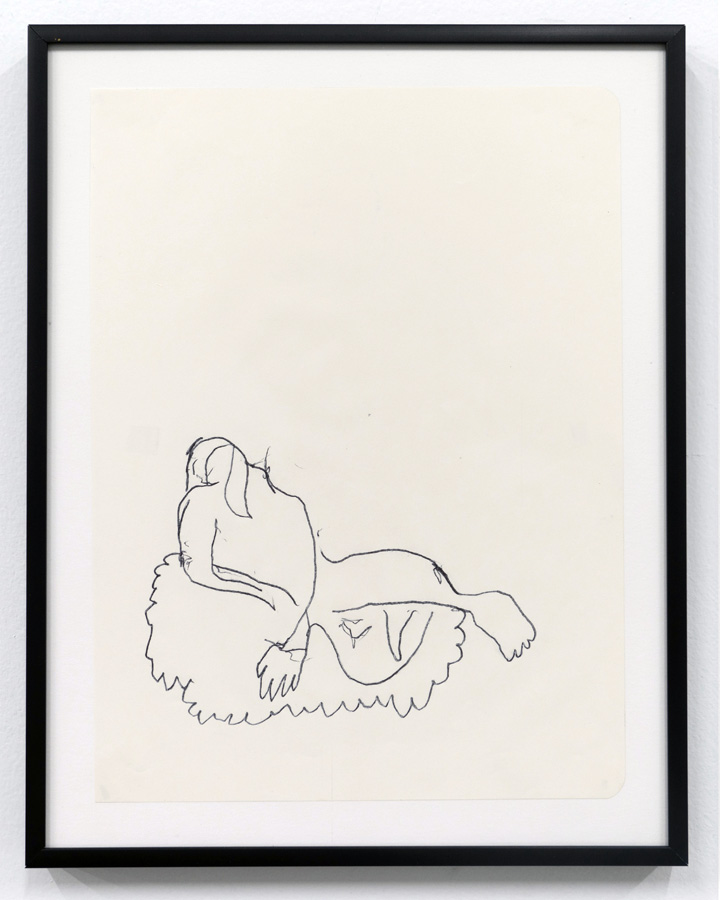

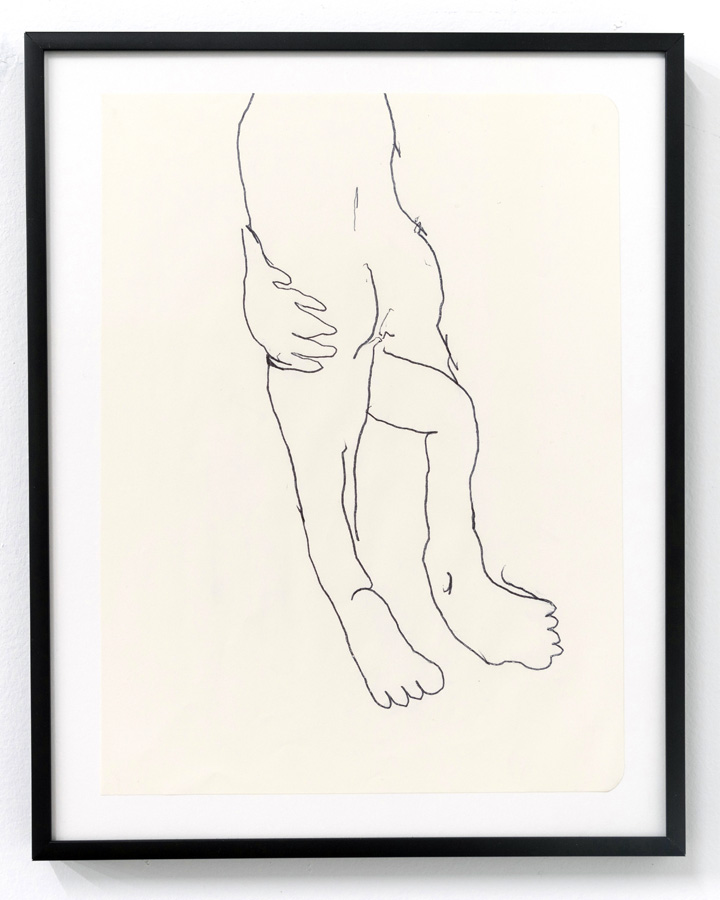

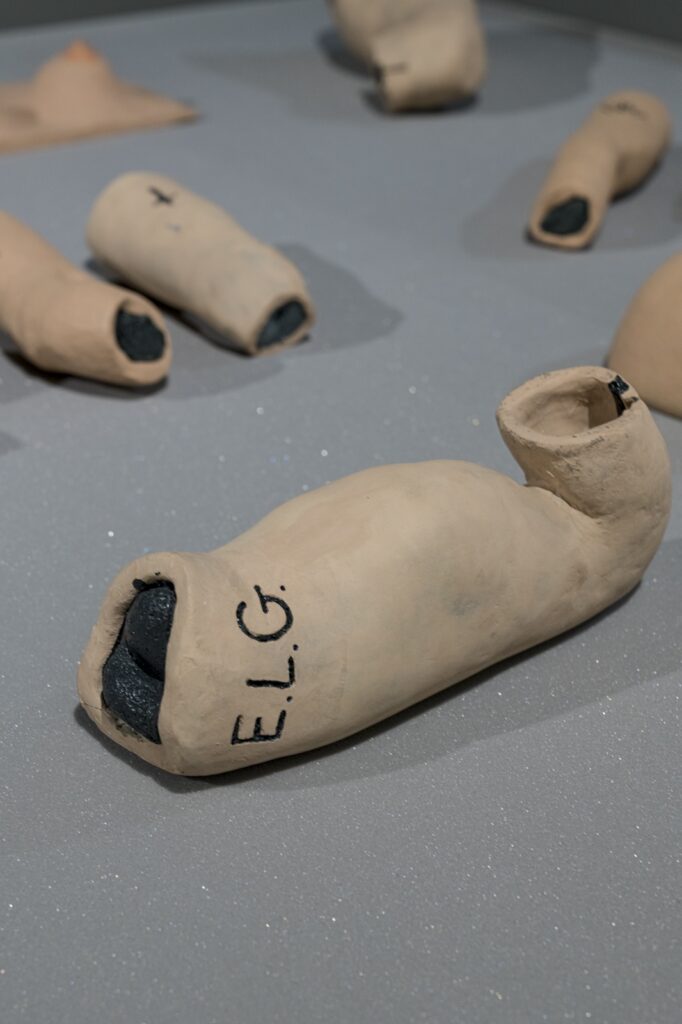

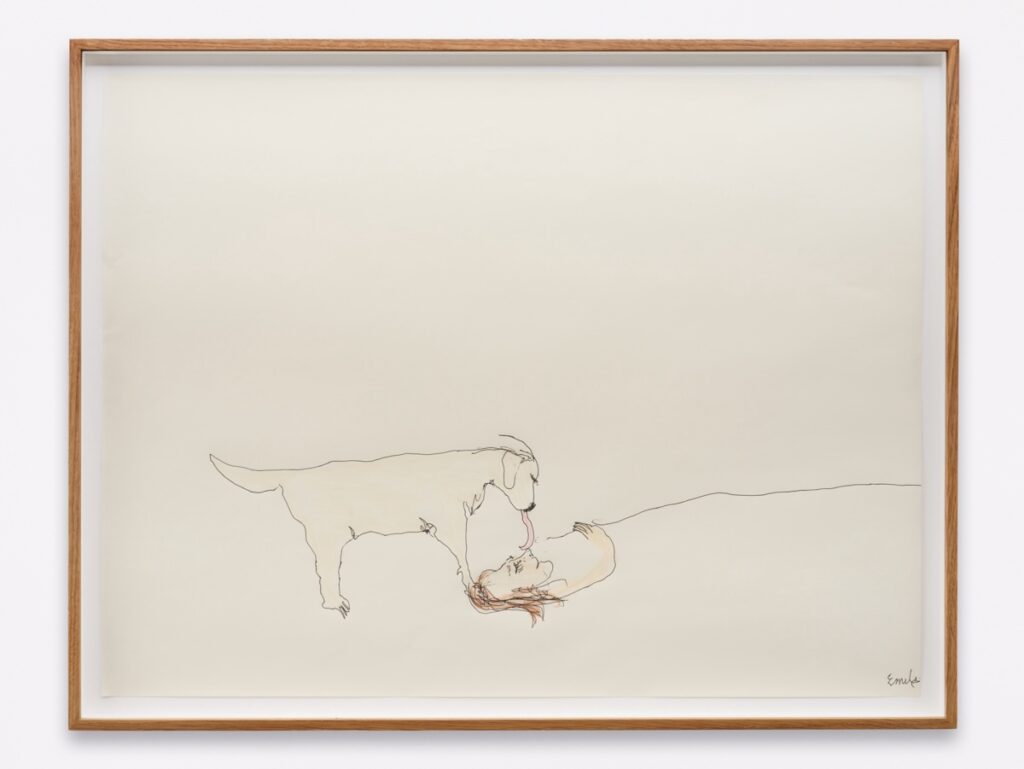

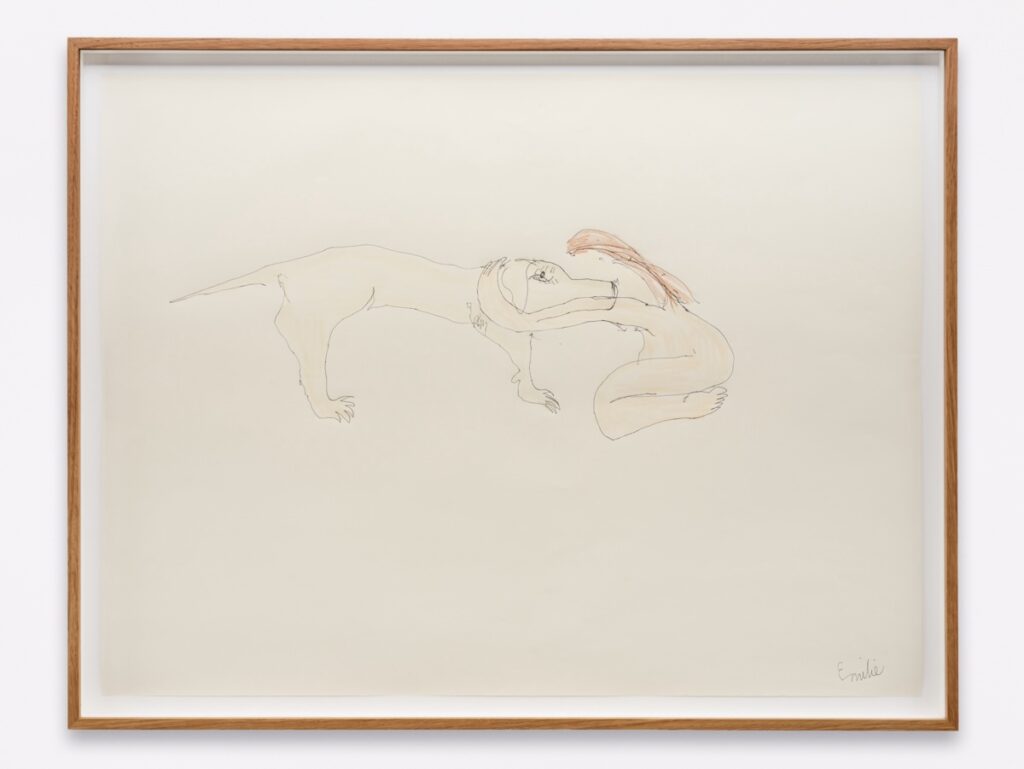

Six blind contour drawings are included in Memory of a Body, Gossiaux creates them using ballpoint pen on newsprint which leaves indentations. Then, she fills in her contours using waxy crayons. Relying on Crayola’s evocative color names like Almond and Piggy Pink, having become blind while she was a student at Cooper Union, Gossiaux either draws from memory or observes her subjects by touch. Sometimes, she renames the colors to remember them better. The six drawings in Memory of a Body depict her guide dog London, a yellow Labrador retriever. Some are mundane (Arm, Tail, Butthole, 2019), some are fantastical (London and the Goddess, 2019), and all are ripe with Gossiaux’s signature: a silly sort of sweetness.

Visible through Mother Gallery’s window are two sculptures of London that are monumental in size. She’s standing on her hind legs with her arms outstretched, ready to rest her paws in yours and sway side to side for a dance. That’s one way London shows affection. Emilie remarked to me that the process of making those papier-mâché sculptures felt a lot like petting her pooch: rubbing a mushy, wet paper pulp onto the dog’s Styrofoam body. She made them while awaiting London’s biopsy results, and wanted to memorialize their good times together (thankfully, the news was good).

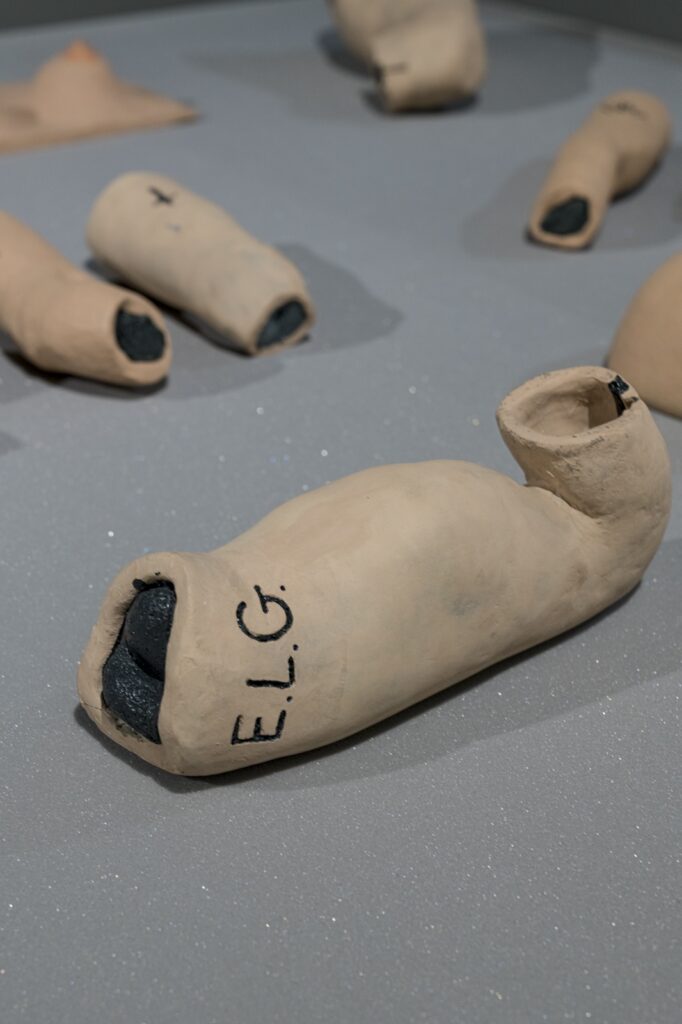

Behind the larger-than-life Londons sits a big blue wedge titled Cerulean: Big Sur, Summer 2010 (Blue Wedge). Reconstructed from the artist’s memory of visiting Big Sur, a California tidal pool, the memory-foam lined piece creates the simultaneous sensations of sinking and floating that characterize swimming in water. And, its triangle shape evokes the invisible, sloping geometry that lies beneath the ocean’s surface known as the continental shelf. Walking alongside the wedge recreates the sensation of walking deeper into the water. The work both reflects the artist’s memory of a good time, and provides a place of rest within the gallery: viewers are invited to sit on the memory-foam-topped wedge. And above the wedge hangs a large circle painted different shades of a fiery orange titled Atomic Tangerine: Looking at the Sun With Your Eyes Closed (2018).

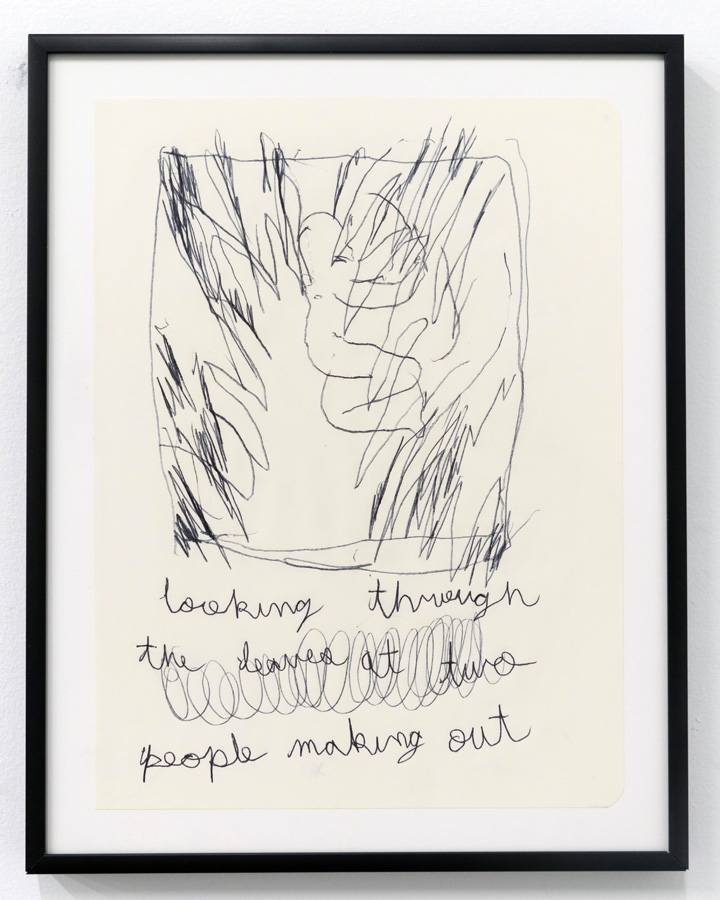

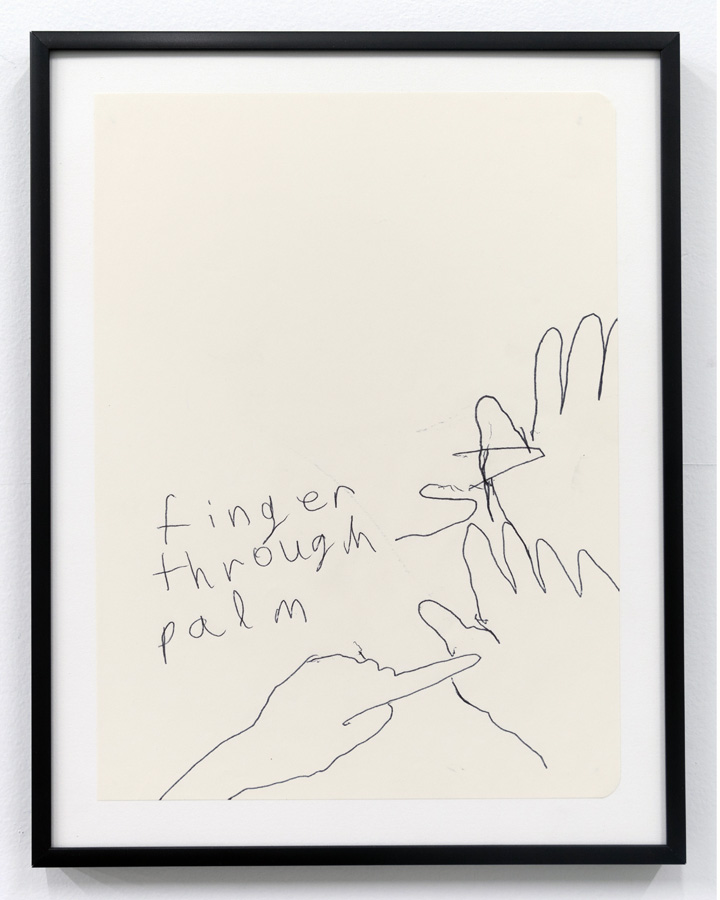

Throughout the gallery are several life-size ceramic sculptures of body parts: a foot, an ankle. Each are inscribed with tattoos belonging either to herself, or to one of her family members. They’re filled with black expanding foam that seeps through the incisions, reminding that tattoos as a form of self-expression are kind of like your insides coming out for others to see. The series is titled “Outerspace” after the name of the sparkly black color Gossiaux chose for the foam; “Atomic Tangerine” and “Cerulean” are Crayola names, too. While these works were made from memory, Finger Through Palm—a papier-mâché sculpture of two hands—depicts a practice for inducing lucid dreaming. If you practice imagining piercing the palm of your hand with your finger while touching one to the other, some say that you’ll start to be able to control your dreams. Gossiaux is a lucid dreamer, which I was not surprised to learn, since her artwork so richly captures her vivid memories.