Emilie Louise Gossiaux: Votives

March 29, 2025 – May 24, 2025

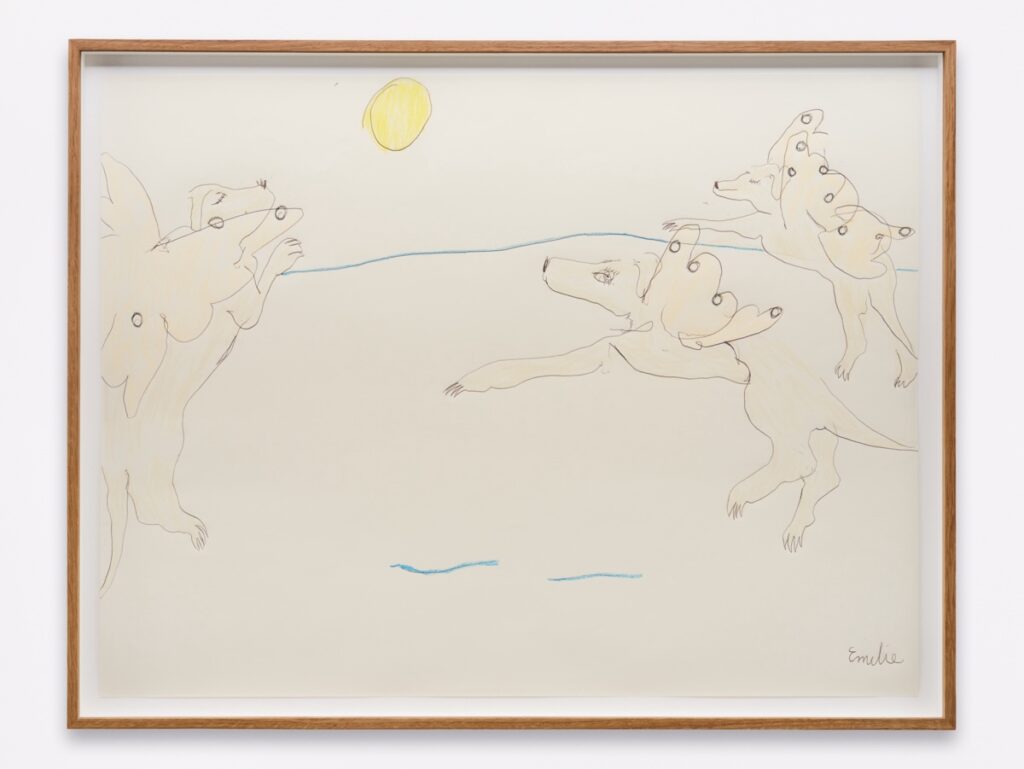

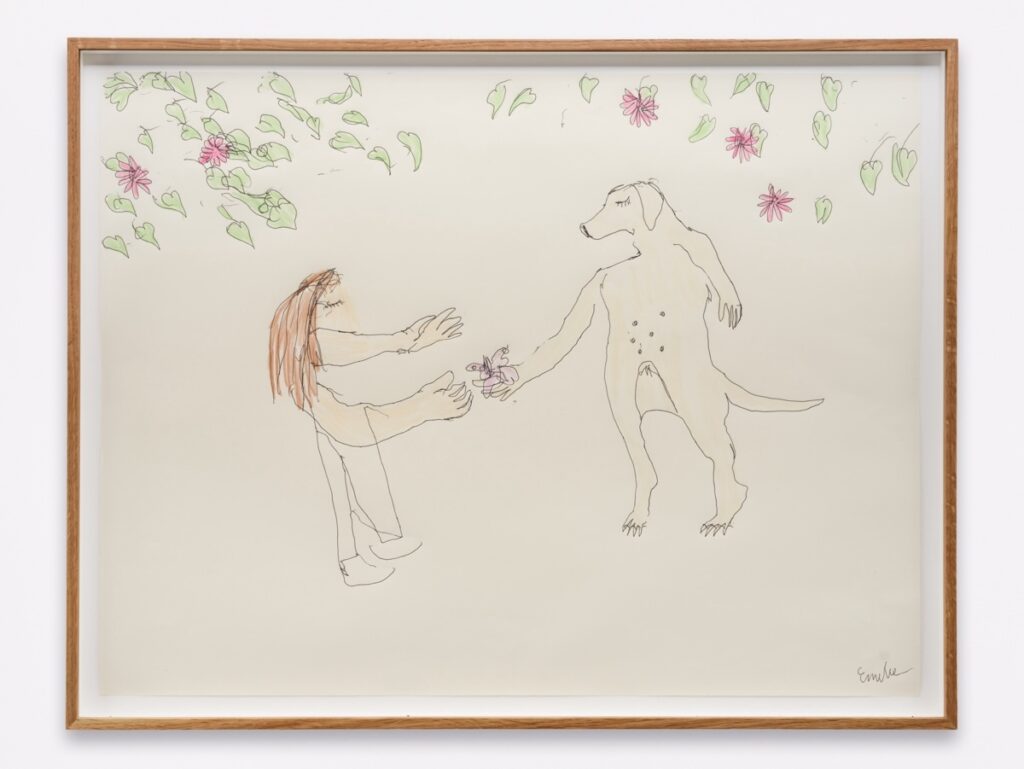

Against a scrim of stars, girl and dog— a specific girl, a specific dog—face one another. Both are bipedal: upright, unattired, similarly scaled, eyes serenely shut. A line unfurls across the middle of the composition to link them belly-to-belly. A leash, an umbilical cord, a sacred ligature: as the particularities of the tie are left open-ended, the fact of the connection—its centrality, its undeniability—feels like a cosmic event.

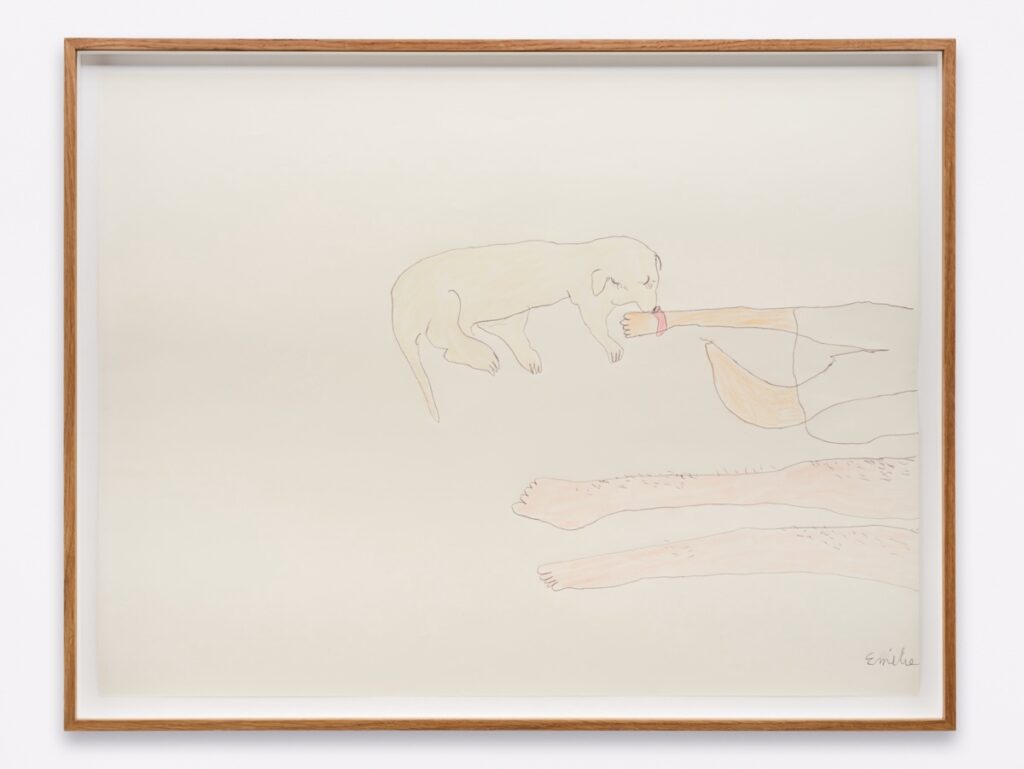

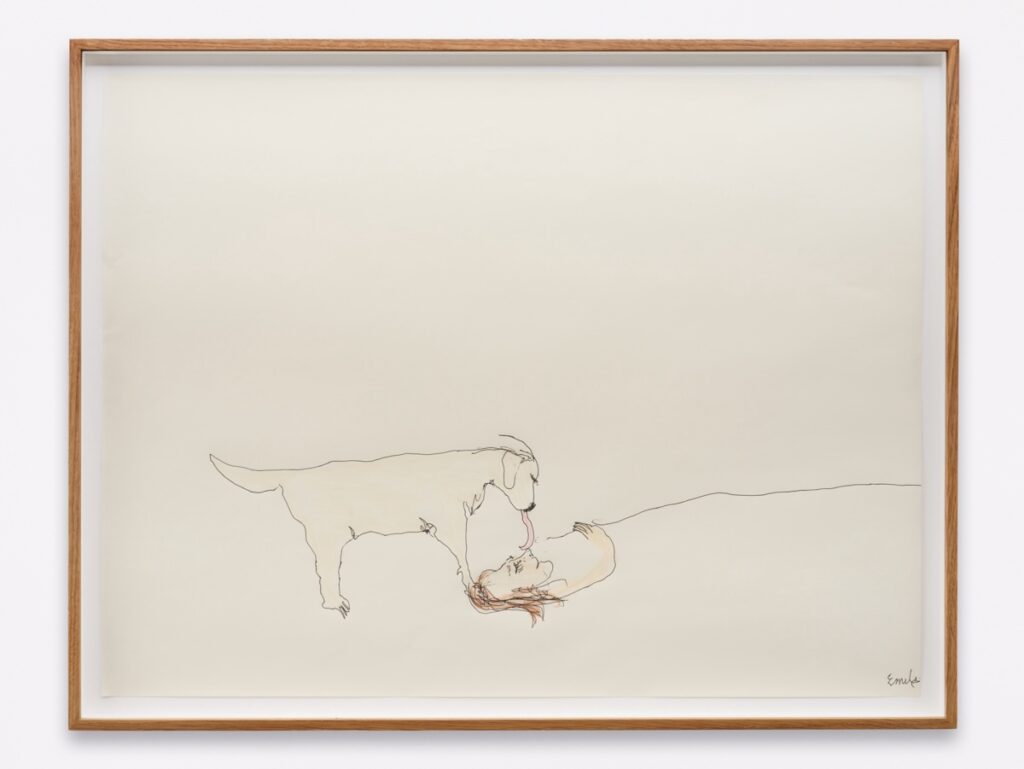

And maybe it is. This ballpoint pen and crayon drawing, Dogs and Humans Figure a Universe (2022), is part of the cosmos of Votives, Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s solo show at CASTLE. Executed using a rubber pad layered beneath the page, with which Gossiaux can feel lines by touch as she moves her pen, the piece depicts the artist with London: a yellow labrador, formerly her guide dog, who is now a senior with reduced mobility.

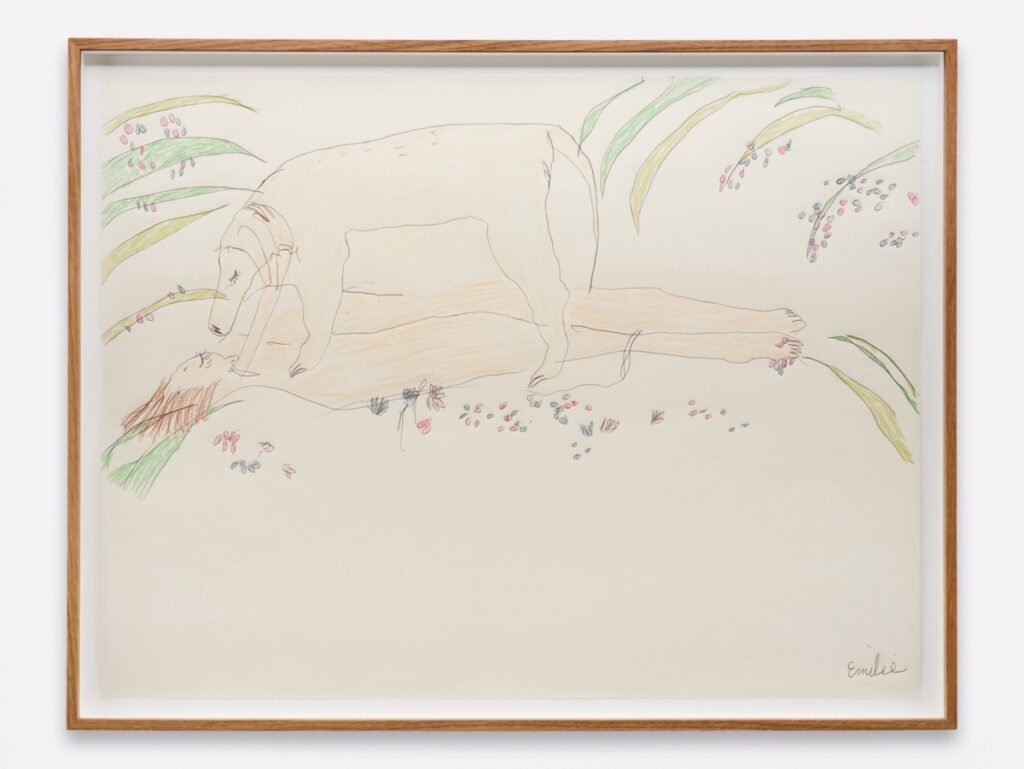

Featuring drawings and sculptures made in the past five years, including a set of new statuettes, the show sees Gossiaux meditating on her evolving relationship with London as well as broader notions of interdependency and kinship across difference. Tenderly, ferociously, the artist rejects the violent mechanisms that deem certain lives and relationships to be insignificant. This rejection is twofold: Gossiaux challenges the hierarchies that assume human superiority to, dominance over, and separation from animals, while also refusing and subverting the dehumanization or ‘animalizing’ of people with disabilities.

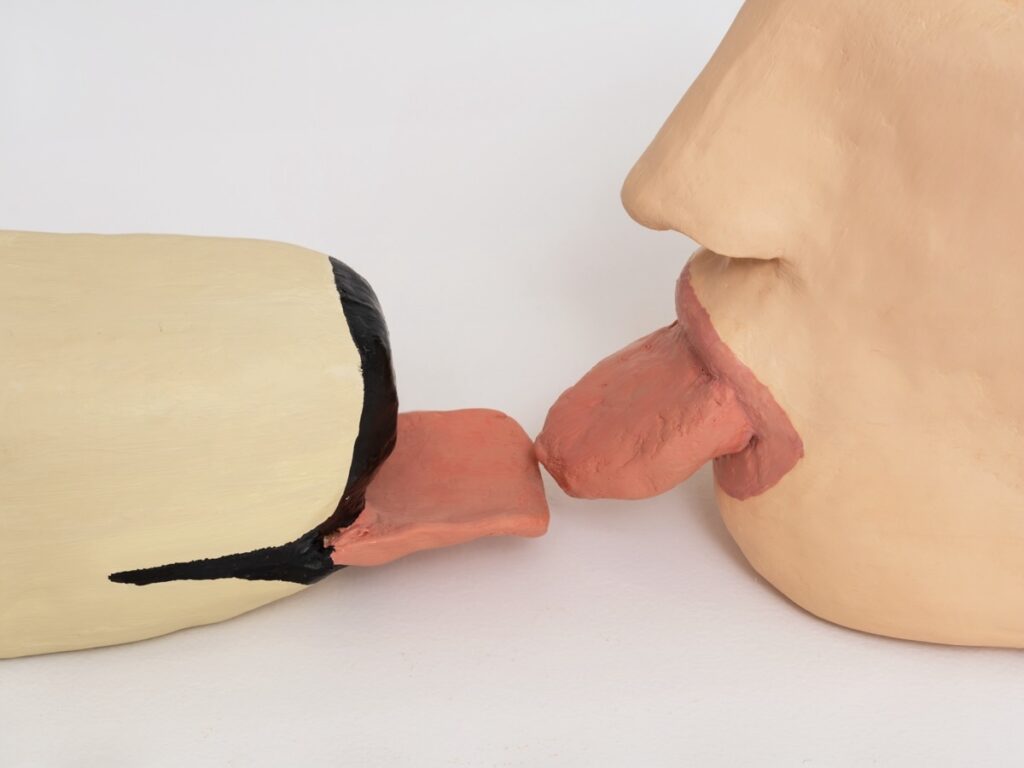

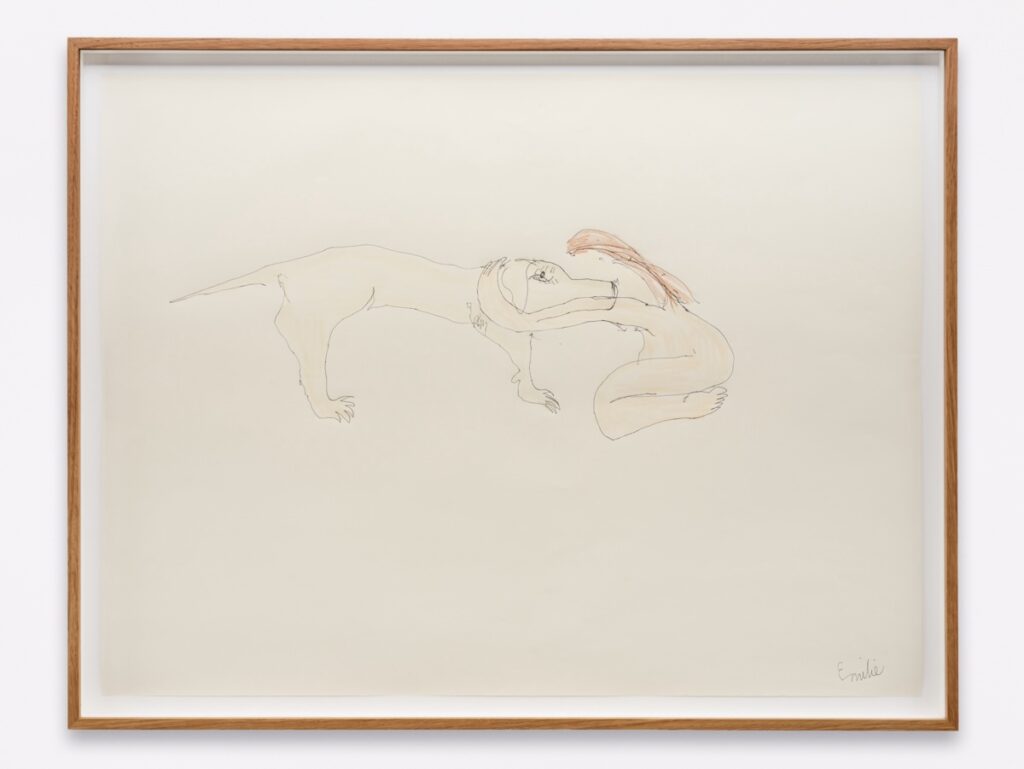

In her work, the line between humans and canines is repeatedly troubled. Dogs adopt humanoid features (or, in a drawing rooted in Gossiaux’s growing interest in animal death rites and afterlifes—London Afterlife [2022]—butterfly wings). People in turn act doglike; subverting the standard order of human-canine greetings, the ceramic sculpture Tongue and Paw (2023) sees a person’s pink tongue extend to lick a paw. This is not to collapse the differences between human and dogs—or purport that companion species relationships are not complicated and even fraught—but to explore a lived, interspecies connection that changes both parties, destabilizing notions of insularity and fixity.

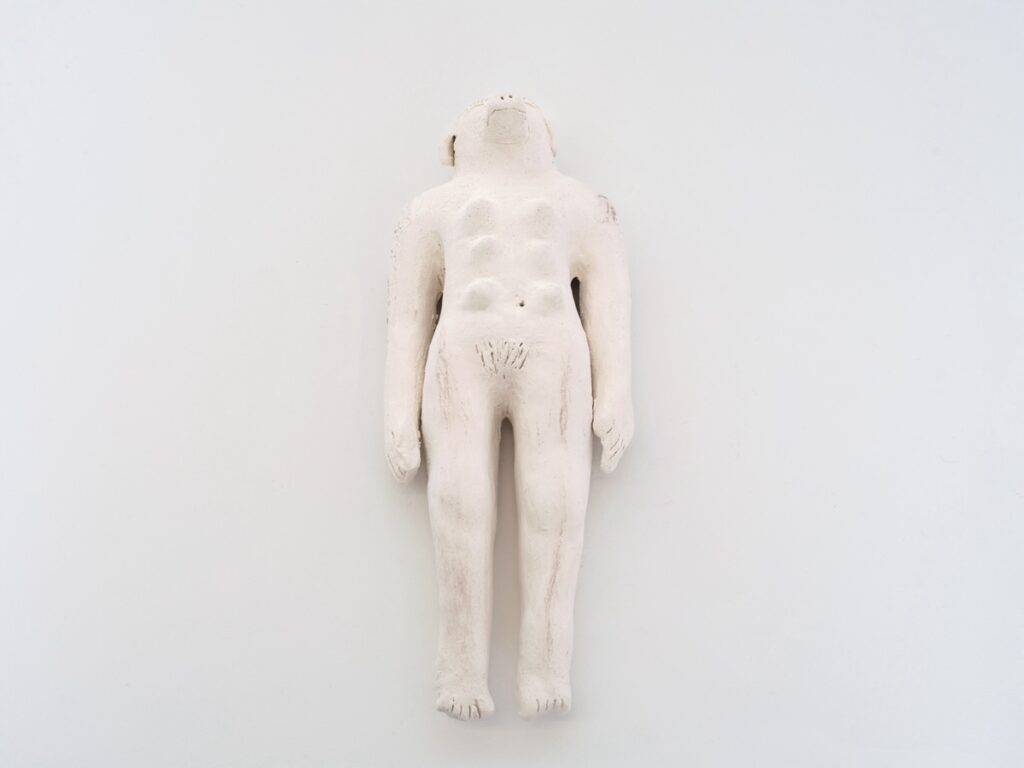

Sometimes, dog and human don’t so much swap—body parts, behaviors, perspectives—as fuse. The Doggirl sculptures—Doggirl, They Called Me (2021), Doggirl (smaller) (2025), and Doggirl (larger) (2025)—each consist of a pale earthenware figure, laid supine, bearing a dog’s head and a woman’s legs. Evoking the potent human-animal hybrids of ancient Egyptian and Greek mythology, the figure suggests a multispecies assemblage wherein the whole indubitably exceeds its parts. Such thinking chimes with Gossiaux’s formulation of a “super-being”: a term she uses, counter to ableist frameworks, to describe her and London’s combined powers. Interdependency—between and beyond humans—isn’t just a fact of existing within a larger ecology; it’s a wellspring.

–Cassie Packard